The problems afflicting China’s economy keep on multiplying. As if the years long real estate slump that is unlikely to end anytime soon and trade war with the U.S. were not enough, there has also been a sharp rise in the number of loss-making Chinese industrial enterprises. Rather than being allowed to fail, these “zombie” firms are being propped by local governments to avoid mass layoffs and keep a lid on social unrest.

According to a June 12th Bloomberg report,[1] 1 out of every 4 of China’s manufacturing firms were bleeding red ink during 2024. That is double the percentage of loss-making industrial companies in 2010-2011 and the highest such figure since 2001. Some Chinese provinces have an even higher proportion of such unprofitable businesses: in Shanxi, for example, 40% of manufacturing enterprises failed to make money last year. Drawing upon Chinese National Bureau of Statistics survey data, an August 8, 2024 article in The Economist[2] put the share of manufacturing enterprises operating at a loss at the end of June 2024 at 30%, noting that this number showed a “startling deterioration” in the business environment for these concerns during the first half of last year. That 30% figure exceeds the previous recorded peak reached during the 1998 Asian financial crisis.

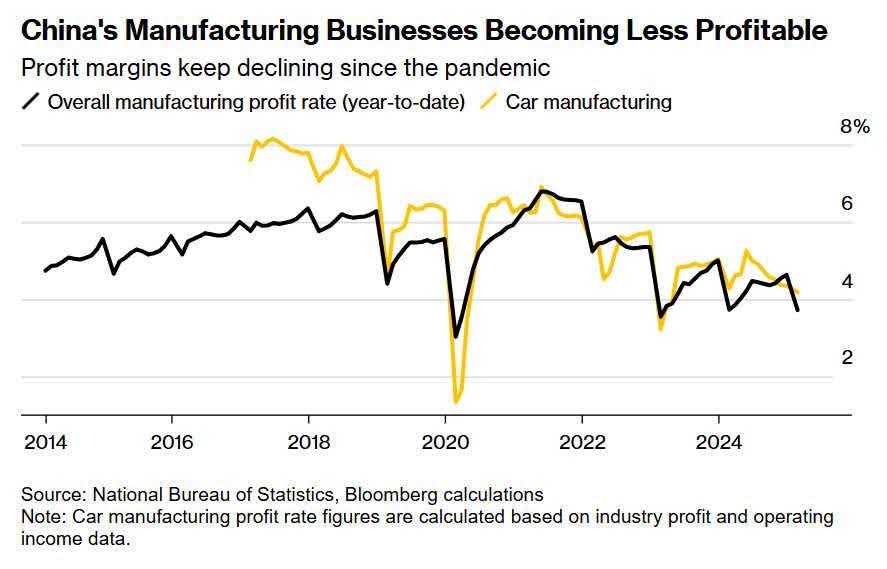

The rising percentage of China’s industrial firms operating in the red reflects a marked decline in profit margins across its manufacturing sectors, with this trend being especially marked among car producers (I plan on doing a deep dive into this industry, particularly electric vehicles (EVs), which have been a poster child for Chinese new found strength in advanced manufacturing activities).

A key factor driving down manufacturing profits in China is government industrial policy under Xi Jinping.[3] Two years after taking power, Xi launched in 2015 the “Made in China 2025” initiative to upgrade China’s industrial prowess by assuming leadership in advanced manufacturing activities, or “new productive forces,” including information technology, EVs, and green energy. This blueprint assumed greater importance following the 2021 real estate crash, which made finding a new economic growth engines to replace housing, which had comprised a quarter China’s GDP,[4] all the more urgent. State support, in the form of cheap loans from the state-controlled banking system and direct subsidies, flowed into industries targeted in the “Made in China 2025” scheme, which were funneled through provincial and local governments. This led to a proliferation of firms and overproduction. In the face of weak household consumption—consumer demand still accounts for under half (39%) of China’s GDP[5]—the gluts in output have given rise to savage price-cutting competition among firms. The end result has been falling profit margins followed by no profits at all.

The profit squeeze on China’s industrial enterprises is being made worse by the trade war between it and the U.S. A June 11th Reuters[6] deep dive into this matter notes that back in April, when Trump imposed a 145% tariff on China, the number of its industrial firms operating at a loss jumped 3.6% year-on-year to 164,467, or just under one-third of all such enterprises. Although these duties were lowered to 30% following the highly adverse reaction from American financial markets, Alicia Garcia-Herrero, chief economist for Asia Pacific at Natixis, notes “People forget, but the current tariff level is already quite painful.”

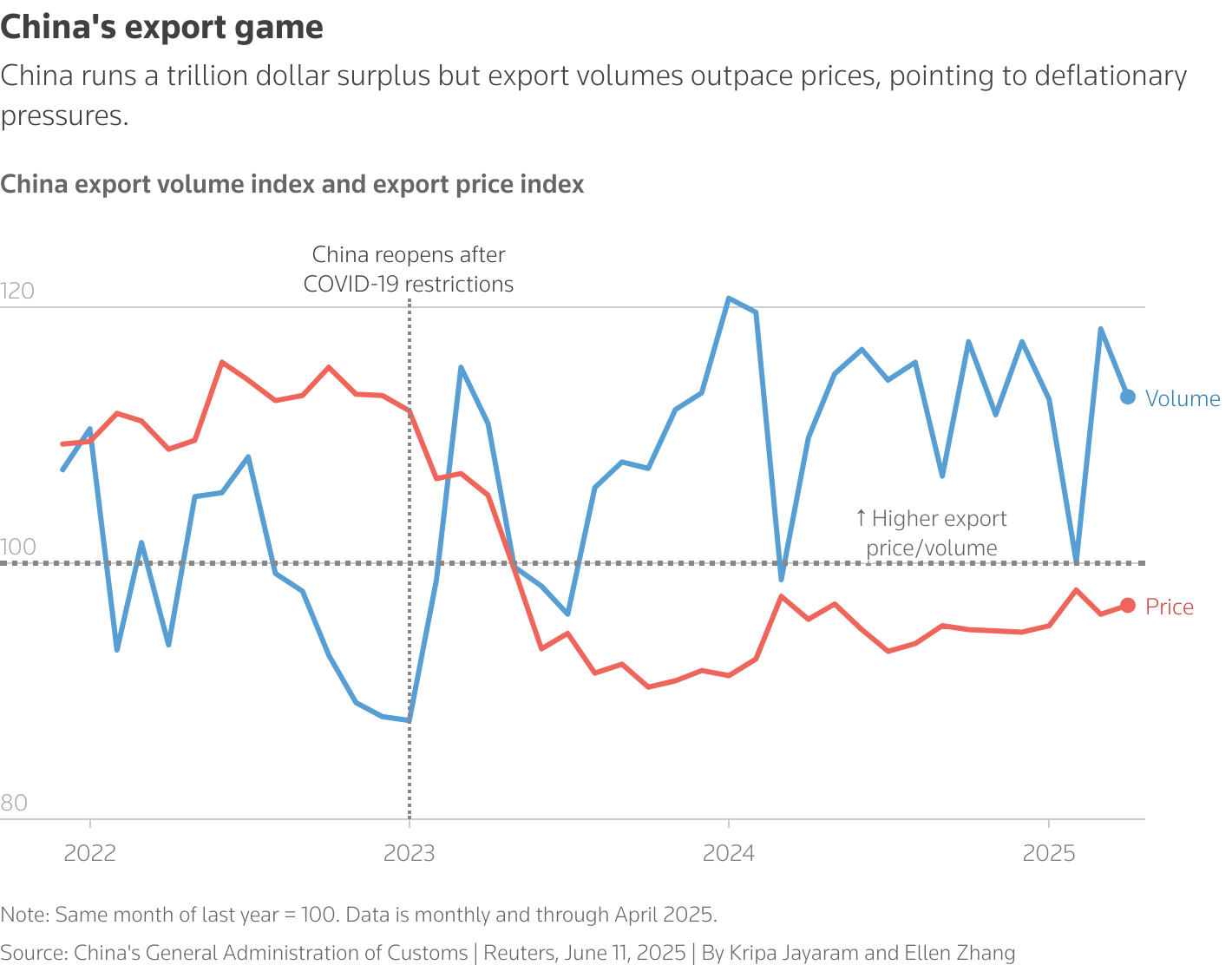

In particular, the high Trump tariffs are forcing Chinese exporters to sell at a loss to keep their U.S. customers, who are demanding lower prices on their products to offset the higher import duties. For example, a marketing manager for a Guangzhou-based medical devices maker tells Reuters that U.S. buyers no longer offer advance deposits for their orders, demanding only to make payments 120-180 days after delivery, adding that with other Chinese companies accepting such terms, the company cannot push back. This behavior, in turn, is giving rise to intense price competition among Chinese manufacturing exporters seeking to retain their share of the U.S. export market in the face of demand that is being constrained by higher tariffs. The outcome is falling prices, with the deflationary pressure that has been overtaking the Chinese domestic economy is now showing up in its export trade picture.

Things may soon be getting worse for the profitability of Chinese manufacturing exporters. The fall in China’s exports to the U.S. has been somewhat offset by the rise in goods sent to Europe, which enabled its overall export growth rate to still hit 4.8% in May. However, the amount of goods China imports from the EU has been shrinking, causing its trade surplus with Europe to hit a record high. On the eve of the upcoming EU-China summit on trade later this month, which has been shortened to just one day in anticipation of it producing few deliverables, EU President Ursula von der Leyen is demanding that China address this trade imbalance[7] as tensions flare between the two actors over a wide variety of specific issues. Thus, Chinese manufacturing exporters may well be losing a critical safety valve for dealing with high U.S. tariffs, further squeezing their profits.

The export firms feeling the greatest pressure are smaller enterprises involved in light manufacturing, who must sell at a loss and/or cut wages and jobs to stay afloat. The marketing manager at the Guangzhou-based medical devices firms cited earlier also informed Reuters that the company had not paid wages for the past two months, due to cash flow issues caused by the new demands of American customers. One quarter of the firm’s staff had quit their jobs. Chen Zhiwu, chaired professor of finance at the University of Hong Kong, observes, “If it lasts more than three or four months, I think many of these small and medium-sized enterprises will not be able to bear it.” Firms that have been particularly hard hit are those in labor-intensive manufacturing sectors, like furniture and toys.[8]

The increasing number and share of Chinese industrial enterprises operating at a loss is confronting Beijing with a severe dilemma. On the one hand, propping up unprofitable firm is akin to throwing good money after bad, and having that support take the form of continued cheap loans will further strain on the already shaky balance sheets of banks. At the same time, the regime is fearful of the mass layoffs and attendant social unrest that will ensue if all the firms bleeding red ink are allowed to go bust.

The post-Covid slowdown in China’s economy has made employment, which has always been a touchy subject for government authorities, even more sensitive politically. To be sure, official government data[9] put the unemployment rate in May at around 5%. But this figure certainly understates the extent of joblessness,[10] due to the odd method by which China calculates the unemployment rate (here, as with a lot of other Chinese government economic data, my view of its veracity echoes a classic Rowen Atkinson line from the hilarious BBC “Black Adder” comedy series: “The greatest work of fiction since vows of fidelity were put into the French wedding ceremony”). Other data points paint a less rosy employment picture—for example, the jobless rate among Chinese aged 15-24 stood at 16.9% in February.[11] In a further sign of a softening labor market, the large online recruitment platform, Zhaopin, earlier this year quietly stopped providing wage data,[12] something it had been doing for at least a decade.

As conditions in China’s economy deteriorate, the amount of social unrest grows. According to the highly respected non-governmental human rights organization Freedom House’s China Dissent Monitor,[13] overall social unrest incidents rose 27% year on year during the third quarter of 2024, with 41% of such events being led by workers. Overall social protest rose further in the last quarter of 2024, by 41%, while the first four months of this year saw economic protests spike to record levels.[14]

Beijing is now caught between a rock and a hard place. Starting in 2023, it had sought to rein in local authorities from supporting chronically distressed businesses. But as the June 12th Bloomberg report makes clear, the central government is now looking the other way as provincial and local leaders throughout China seek to keep firms that would otherwise go under afloat.

In Shanxi Province, the 40% of industrial firms losing money include those involved in “new productive forces” type manufacturing activities. A poster child here is the Dayun Group, which made its mark as a well-known maker of motorcycles before entering the fledgling EV sector in 2017 (in hindsight, they should have stuck to producing motorcycles). Dayun began by producing compact electric SUVs, before pivoting into premium EVs, acquiring the Yuanhang luxury EV sedan and SUV brand. When none of these moves worked out in China’s hyper competitive EV market, Dayun faced court-ordered restructuring in 2024. Despite this and the company laying off half of its workforce, it is still operating, producing trucks, thanks to drip support from Shanxi provincial authorities.

Neighboring Shaanxi Province shows that the lifeline provincial authorities have thrown out to distressed firms extends to enterprises in traditional industries, as well as cutting edge manufacturers. The former includes the 69-year-old Qinyang Changsheng Brewing Company distilling the old-fashioned potent Chinese spirit called báijiŭ (白酒)—that literally means “white [白] alcohol [酒]” and, yes, I imbibed my share of it while living in China—using archaic and inefficient production methods. Changsheng has not turned a profit since 2020 and, like Dayun, is on government life support as it bleeds more and more red ink.

As these cases make clear, provincial and local Chinese authorities are prioritizing preserving employment and social stability over cutting excess manufacturing capacity and focusing government support on profitable companies. In this respect, industrial policy has devolved into a tool for poverty alleviation by ensuring that workers in firms that are, to be blunt, circling the drain, remain employed and retain access to their wages and, down the road, pensions. China would do much better if it strengthened its threadbare safety net for unemployed workers,[15] which would make it easier to put firms like Dayun and Changsheng out of their misery. As things stand now, these firms will turn into “zombie” companies, which have little to no chance of ever being viable again and stagger along thanks to a continual stream of cheap credit. The large-scale presence of such firms in Japan’s economy during the 1990s played a major role in its “lost decade”[16] of slow economic growth.

China is by no means doomed to follow in 1990s Japan’s footsteps. However, to avoid going through its own lost decade, it will have to, among other things, adjust its industrial policy model to curb the kind of savage competition and price wars that have greatly squeezed profits in sectors like EVs. There are now encouraging signs that government authorities at least recognize that such excessive competition, which they are calling “involution, or “nèi juǎn (内卷),” is a serious problem[17] (whether they can address it is another matter, to be taken up in another blog post).

More fundamentally, China needs to make real progress rebalancing its economy toward consumption and away from investment. Doing that would not just help address the “involution” problem by limiting the amount of money thrown at “new productive forces,” as resources are shifted from these parts of the economy to social protection, thereby reducing the proliferation firms in such industries. It would also enable China’s domestic market to better absorb its manufacturing output and limit the need to run up large current account surpluses with the rest of the world to maintain growth. That, in turn, could reduce the impact of trade tensions in squeezing the profitability of exporting manufacturing firms, many of which are likely viable enterprises, who would be less dependent on foreign demand for their goods.

One thing is for sure, fighting the nascent epidemic of zombie firm is a critical part of putting China on a long-term sustainable economic growth path.

UPDATE: MORE DISCOURAGING INFLATION NEWS

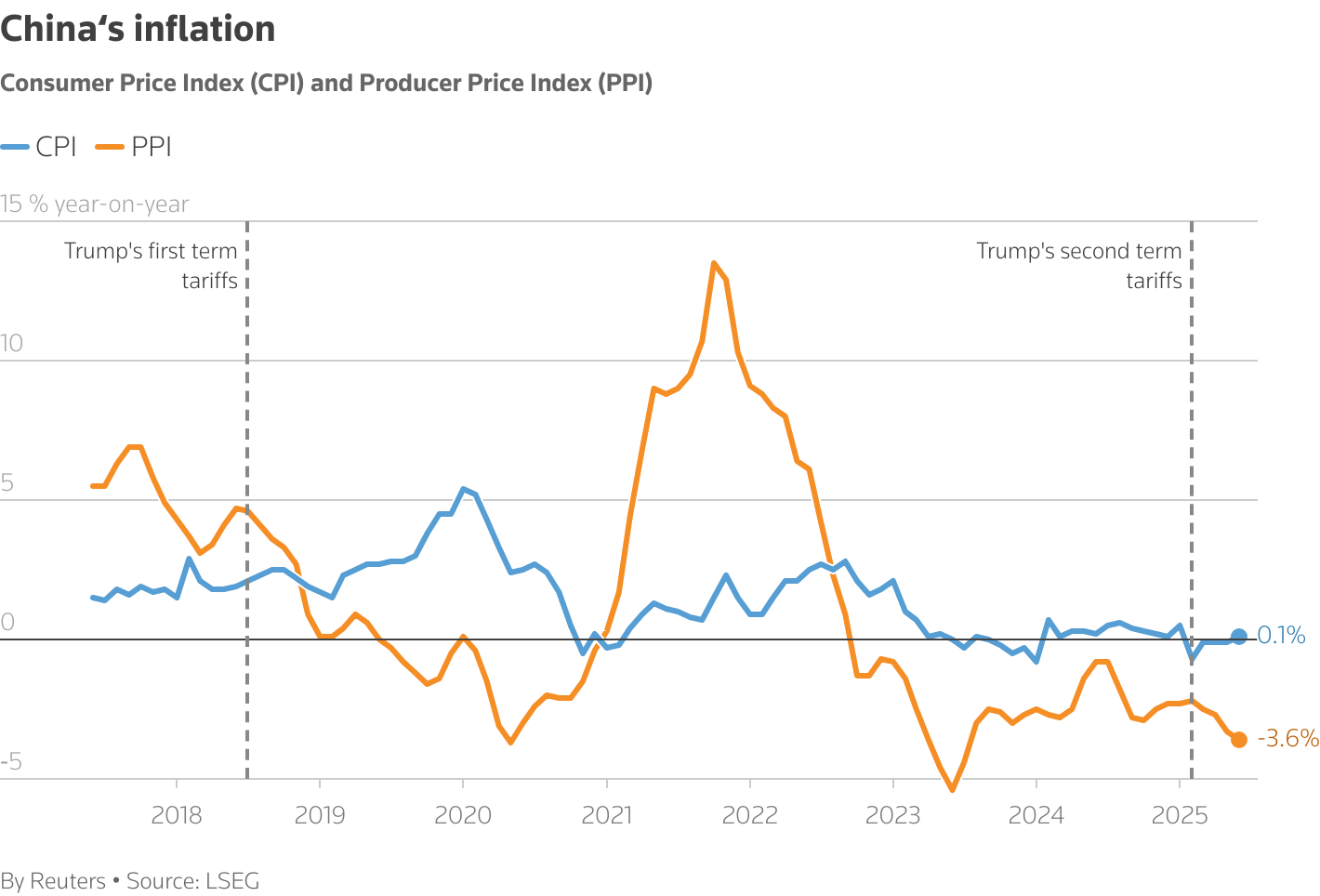

The June inflation data is now in[18] and, at the risk of sounding like a broken record, it’s once again very ugly. The news regarding the producer price inflation (PPI) was especially dreadful, with factory gate prices tumbling 3.6% in June from last year. This fall in the PPI was steeper than the 3.3% decline in May and the largest drop since July of 2023. The PPI has now fallen for 33 straight months in a row. The consumer price index (CPI) crept up 0.1%, reversing the 0.1% drop in May. The CPI has flatlined since early 2023.

The threat of deflation continues to loom over China’s economy.

[1]. “China Forced to Keep Unprofitable Firms Alive to Save Jobs and Avoid Unrest,” Bloomberg, June 12, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2025-06-12/xi-keeps-china-s-unprofitable-businesses-alive-to-save-jobs-and-avoid-unrest.

[2]. “China’s Manufacturers are Going Broke,” The Economist, August 8, 2024. URL: https://www.economist.com/business/2024/08/08/chinas-manufacturers-are-going-broke.

[3]. “China’s Manufacturers are Going Broke,” The Economist, August 8, 2024. URL: https://www.economist.com/business/2024/08/08/chinas-manufacturers-are-going-broke.

[4]. Kenneth Rogoff and Yuancheng Yang, “Sliding Property Prices May Presage Painful Economic Adjustment,” F&D, Finance and Development Magazine, International Monetary Fund, December 2024. URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/fandd/issues/2024/12/chinas-real-estate-challenge-kenneth-rogoff.

[5]. Logan Wright, Camille Boullenois, Charles Austin Jordan, Endeavour Tian, and Rogan Quinn, “No Quick Fixes: China’s Long-term Consumption Growth,” Rhodium Group, July 18, 2024. URL: https://rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/.

[6]. Casey Hall and Ellen Zhang, “As US Trade Truce Gets Back on Track, Some Chinese Exporters are ‘Slowly Dying,’” Reuters, June 11, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/us-trade-truce-gets-back-track-some-chinese-exporters-are-slowly-dying-2025-06-11/.

[7]. Michal Kubala and Max Ramsay, “EU Chief Demands China Address Trade Imbalance as Tensions Flare,” Bloomberg, July 8, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-07-08/eu-chief-demands-china-address-trade-imbalance-as-tensions-flare.

[8]. Antoni Suldkowski and Laurie Chen, “Inside China’s Decision to come to the Table on Trump Tariffs,” Reuters, May 9, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/inside-chinas-decision-come-table-trump-tariffs-2025-05-09/.

[9]. “China Unemployment Rate,” Trading Economics, No date. URL: https://tradingeconomics.com/china/unemployment-rate.

[10]. Mary Hui, “’Suspiciously Stable:’ How China’s Unemployment Rate is Calculated,” Quartz, July 20, 2022. URL: https://qz.com/1858923/coronavirus-how-china-calculates-its-unemployment-rate.

[11]. “China’s Youth Jobless Rate Rises to 16.9% in February,” Reuters, March 19, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-youth-jobless-rate-rises-169-february-2025-03-20/#:~:text=The%20urban%20jobless%20rate%20for,at%204.3%25%20from%204.0%25.

[12]. “China Wage Data Goes Missing as Tariffs Imperil Millions of Jobs,” Bloomberg, May 9, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-05-09/china-private-wage-data-goes-dark-with-jobs-at-risk-from-tariffs.

[13]. “Report,” China Dissent Monitor 2024, Freedom House, July-September 2024. https://freedomhouse.org/report/china-dissent-monitor/2024/issue-9-july-september-2024.

[14]. Rebecca Choong Wilkens, “China’s Economic Protests Spike in Record Ahead of Tariff Shock,” Bloomberg, April 17, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-04-17/china-s-economic-protests-spiked-to-record-ahead-of-tariff-shock.

[15]. Nicholas Lardy and Tianlei Huang, “China’s Weak Social Safety Net will Dampen its Economic Recovery,” Peterson Institute of International Economics, May 4, 2020. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/china-economic-watch/chinas-weak-social-safety-net-will-dampen-its-economic-recovery.

[16]. Richard J. Caballero, Takeo Hoshi, and Anil K. Kashyap, “Zombie Lending and Depressed Restructuring in Japan,” American Economic Review, Volume 8, 1977, pp. 1943-1977. URL: https://economics.mit.edu/sites/default/files/publications/Zombie%20Lending%20and%20Depressed%20Restructuring%20in%20Japa.pdf.

[17]. Evelyn Cheng and Bernice Doi, “Involution or Evolution? China Wants to Stop the EV Price War, but Analysts are Doubtful,” CNBC, June 5, 2020. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/06/05/involution-or-evolution-china-wants-to-stop-the-ev-price-war-but-analysts-are-doubtful.html.

[18]. “China’s Factory-Gate Deflation Worst in Two Years as Trade War Bites,” Reuters, July 8, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-consumer-prices-rise-first-time-five-months-2025-07-09/#:~:text=On%20a%20monthly%20basis%2C%20the,the%20highest%20in%2014%20months.