When President Trump declared “Liberation Day” on April 2, 2025, imposing what amounted to an embargo against Chinese good, China was hardly a paragon of robust economic health. To be sure, in the wake of its lackluster post-Covid economic recovery, the first quarter of this year was marked by a few green shoots. These included a rise in corporate profits and increase in retail sales. However, even here the picture was rather mixed. At the same time, the housing market remains in the red, while households face uncertainty in employment and anemic wage growth. These problems, in turn, are reflected in ongoing stagnant or falling prices and the looming threat of a deflationary spiral.

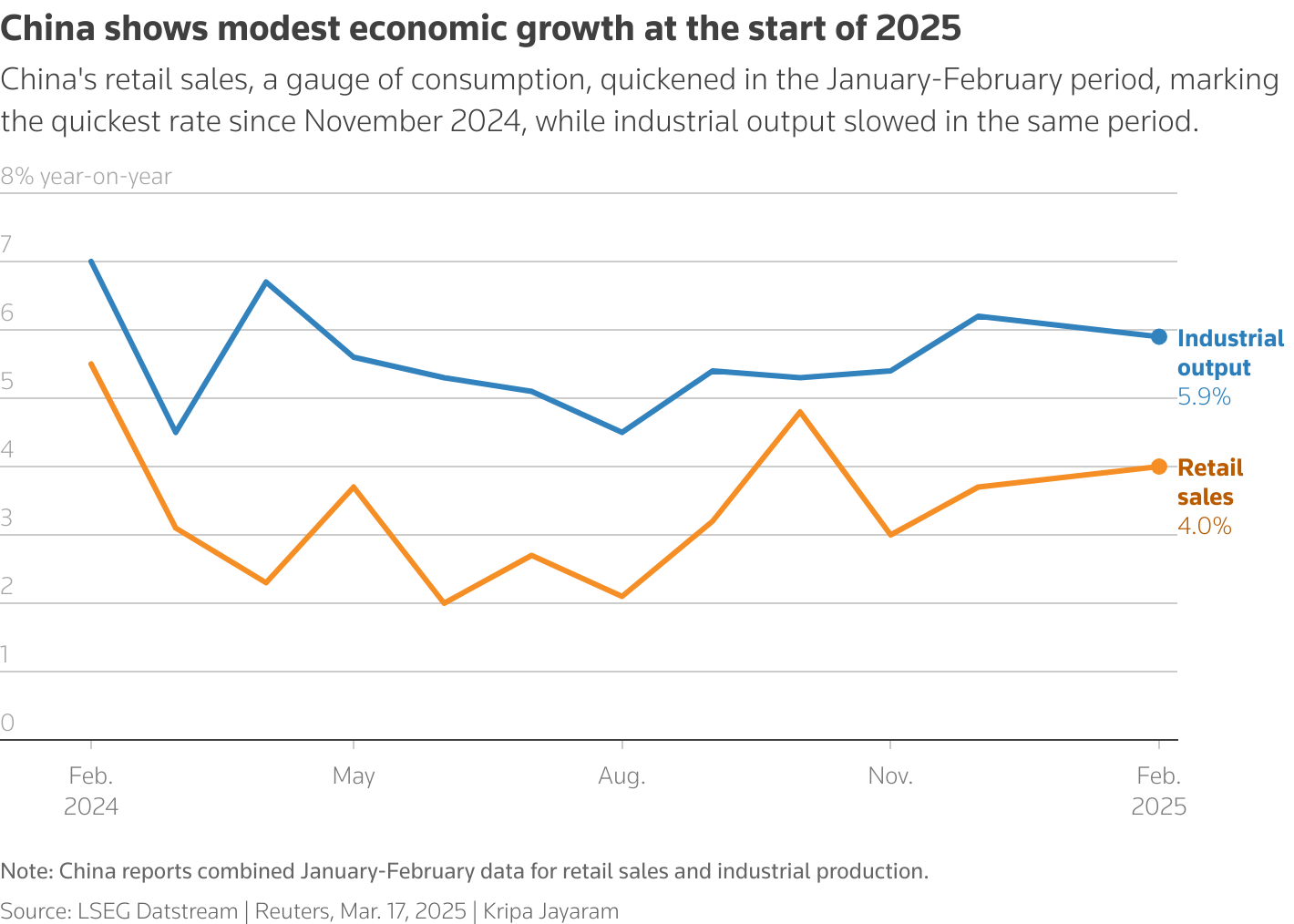

First, the green shoots. According to Chinese Government official data, profits at Chinese industrial firms rose by 0.8% during the first quarter of 2025. At the same time, March saw the release of somewhat better numbers regarding retail sales, a key gauge of consumption. These sales jumped by 4.0% in January-February, exceeding the 3.7% rise in December, marking the fastest growth since November of 2024.

While these latest data are certainly good news, we should not get carried away. In the case of industrial profits, the first quarter rise was a very modest uptick. This increase also came on the heels of earlier dips in industrial profits, which fell by 0.3% during the first 2 months of this year after sharply contracting over the previous three years. Moreover, much of the latest boost in profits appears to have been driven by a government consumer goods trade-in and equipment upgrade scheme, whose impact will certainly be transitory. Finally, the ongoing decline in factory gate prices, as measured by the producer price index (PPI)—more on that later—will continue exerting downward pressure on the earnings of manufacturing firms. Thus, after noting in CNBC that “the mood on Chinese economy is definitely improving,” Robin Xing, chief China economist at Morgan Stanley, cautions “it is still showing a mixed bag,” adding that “corporate profit is still lagging and consumer sentiment is still at subdued levels.”

Speaking of consumer sentiment and consumption, the outlook for China’s economy, notwithstanding the recent retail sales data, is decidedly mixed. One problem is the growth of consumption continues to lag behind industrial output, which jumped by 7.7% in March, beating market expectations of a 5.6% rise and accelerating from the 5.9% growth recorded in January-February. It bears noting that the gap between retail sales and industrial output widened in early 2025 after closing late last year, even before the March surge in the latter.

As is the case with industrial profits, the latest spurt in retail sales numbers owes a lot to the recently expanded government 300 billion RMB ($41.5 billion) trade-in scheme for consumer goods, which included electric vehicles, appliances, cell phones, and the like. Senior Economist Intelligence economist Xu Tianchen notes in a March 17th Reuters article, “Retail sales growth was decent, reflecting the vital role of subsidies in supporting home appliances and mobile phone sales,” while adding that the effects of these efforts may “fade over time,” with auto sales already dropping.

Another strong reason for believing that the latest rise in retail sales may be a blip on the screen is ongoing weakness in consumer sentiment. According to the National Bureau of Statistics, a key gauge of that sentiment, the Consumer Confidence Index, has remained stuck at 86 points into 2025, a sharp fall from its high of almost 200 points in 2021.

A final indicator of the mixed picture regarding the latest Chinese consumption trends are purchases made by travelers over the latest two weeklong holidays, the Spring Festival (Chinese New Year) and May Day celebration. Chinese consumers opened their wallets during the Lunar New Year, with domestic tourism spending reaching 677 billion RMB ($92.9 billion), a 7% year-on-year increase, while per capita expenditures increased by 9% compared to pre-pandemic levels. These highly favorable numbers were certainly one factor juicing up the Q1 retail sales figures. However, the domestic travel data for the May Day “golden week” holiday tell a quite different story. While Chinese domestic tourists’ spending rose by 8% year-on-year during this holiday to 180.27 billion RMB ($24.92 billion), this figure was still below pre-pandemic levels. At the same time, service activity in China grew at its slowest pace in seven months during April.

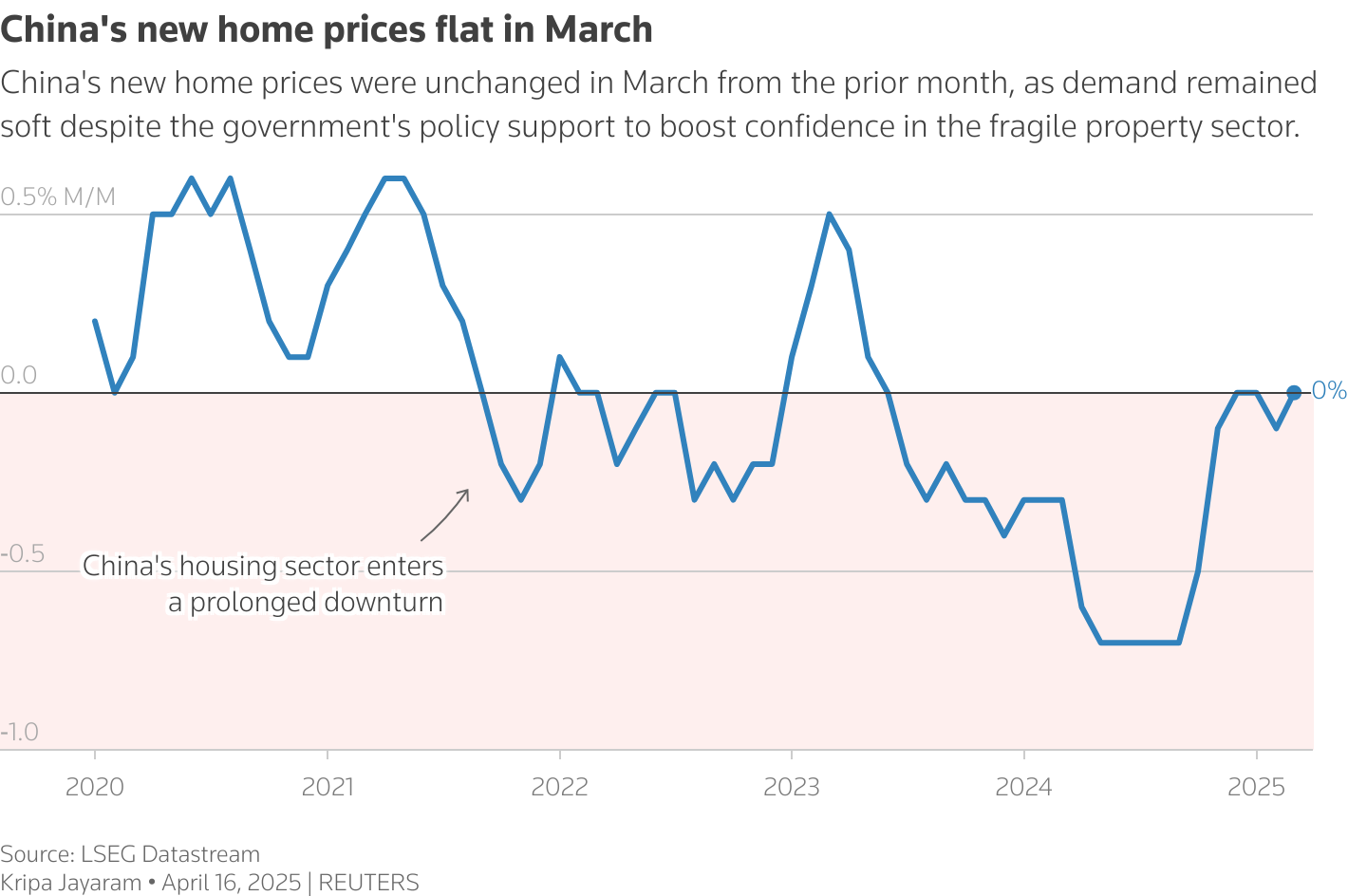

One key factor driving the ongoing weakness in Chinese household consumption is the continued bad state of the residential real estate market. The year began with a sharp fall in home price, with the average price per square meter in existing residential properties in China’s top 100 cities going down by a little over 7% in January from a year earlier, while the value of property sales by the top 100 real-estate developers fell by nearly 17%. Although new home prices stabilized in March, as the drop in prices moderated, this sector of the residential housing market remained in the red all through Q1 of 2025.

As an April 15th report in Reuters notes, official Chinese Government National Bureau of Statistics data indicates that resale home prices fell across the board on annual basis, even as the small number of Tier 1 cities in China saw a marginal monthly rise in March over February. Property sales by floor areas dropped by 3% during Q1, while investment in real estate fell by 9.9%. With some 70% of the wealth of Chinese households still tied up in their homes, the failure of the residential property market to rebound continues to act as a major drag on consumer spending.

Uncertainties around employment and wages constitutes the other main factor weighing down Chinese household consumption. Even official Chinese Government nationwide employment surveys point to rising job insecurity across all age groups during the first quarter of 2025. According to this data, the urban job rate hit 5.4% at the beginning of March, the highest in two years. While all age groups experienced employment difficulties, the problem was especially acute among those aged 16-24. The urban unemployment for this age bracket, excluding students, rose to just under 17%. The anemic job market has translated into stagnant employee wages. A March 21st report by the Hong Kong-based HR consultancy, Willis Towers Watson (WTW), states that their research “shows that salary increases will likely stay low in 2025.” This prediction dovetails with the results of a survey conducted by the Robert Half hiring site, in which 70% of employees said that “negotiating salaries has become more challenging compared to last year.”

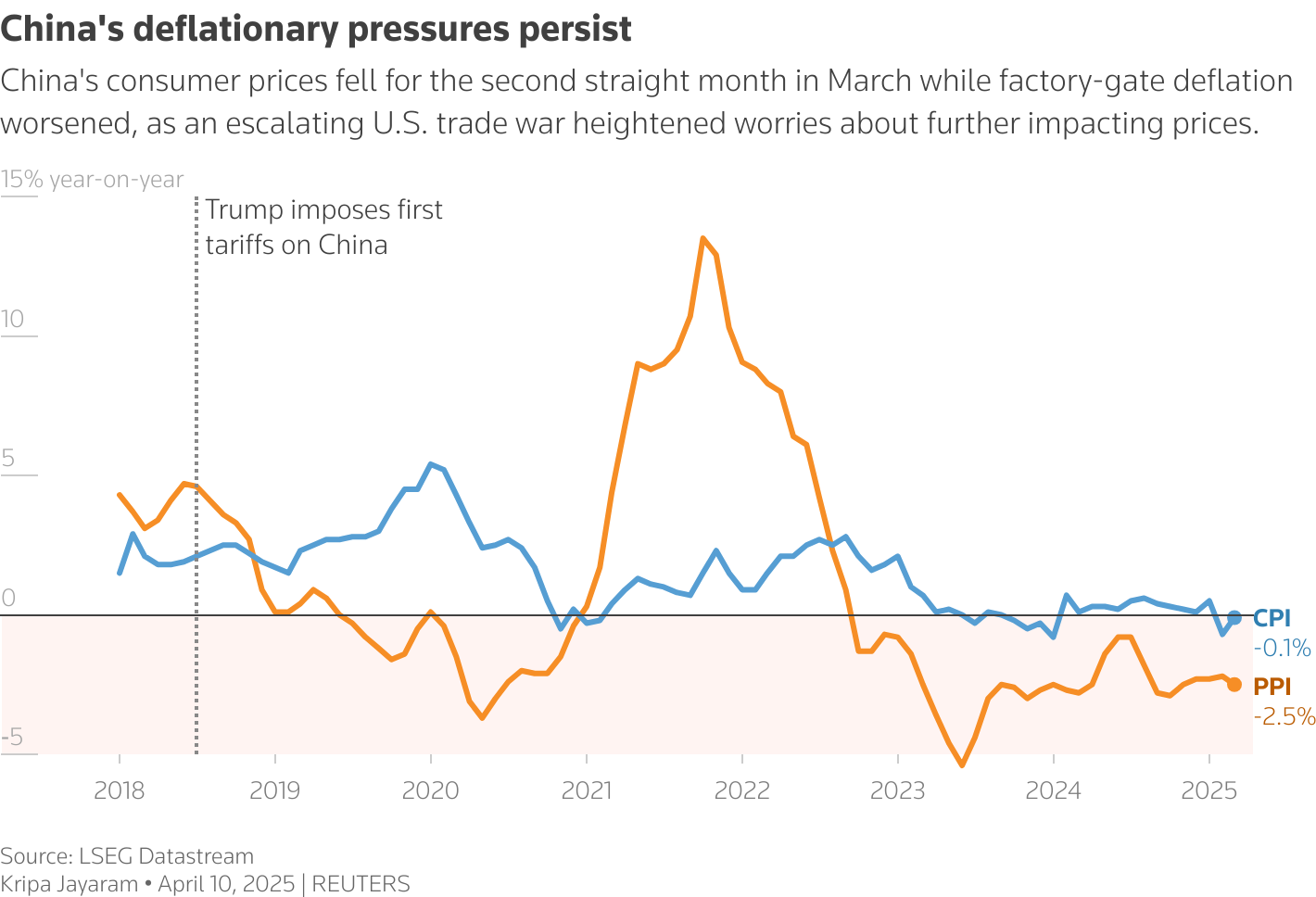

Given the mixed data on retail sales, combined with the still bad state of the housing market and growing pressure on employment and wages, it comes as no surprise that deflation continues to stalk China’s economy. An April 10th Reuters summary of the latest Q1 price data notes that the consumer price index (CPI) dropped 0.1% in March from a year earlier, after declining 0.7% in February. Moreover, the PPI remained in the red, plunging 2.5% in March from a year earlier, the weakest reading in four months and marking the 30th straight month of decline.

Thus, in the April 10th Reuters article, Julian Evans-Pritchard, head of China economics at Capital Economics, soberly notes, “Deflationary pressures persisted last month and will almost certainly deepen over the coming quarter as it becomes more difficult for Chinese firms to export their excess supply.” This prediction was borne out by the post-Q1 April price numbers. As Reuters reports, the PPI fell sharply by 2.7%, a worse year-on-year decline than in March, while the CPI shrank by 0.1% from a year ago, matching the previous month’s 0.1% decline. As Zhang Zhiwei, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management, states in the Reuters’ review of the April price data, “China faces persistent deflationary pressure” which “may rise in the coming month as exports will likely weaken.”

The looming specter of deflation, which is rooted in the inability and reluctance of ordinary Chinese to buy more goods and absorb China’s continually rising output of manufactured goods, underscores the failure of government efforts to rebalance the economy toward consumption. Lynn Song, Chief China Economist at Greater China at International Netherlands Group (ING), is right to argue in an April 28th CKGSB Knowledge article on Chinese consumer spending that the goal of making consumers the main economic growth engine remains “a work in progress.”

Last but not least, it is important to stress that China’s less than stellar 2025 Q1 numbers preceded the Trump 2.0 trade war against the People’s Republic. Although the reasons Trump and his advisors provide for this particular trade seem to change by the day, one underlying, if unspoken rationale, is to weaken China economically. The latest economic numbers show a China that was already weakening economically. As I have argued in my other blog posts, the combination of highly adverse demographic trends, an unsustainable economic growth model, and increasingly poor and top-down leadership will by itself drive the Chinese economy into the ditch. Trump administration trade policies will certainly accelerate that decline by striking at the one recent bright spot in the Chinese economy, its exports, but are also causing extensive collateral damage to the US economy.

I will have to say about this and the new Sino-American trade war soon.