The string of recent largely disappointing economic data drops from China continued during the late summer, underscoring ongoing structural problems in the world’s second largest economy. While deflationary pressure eased a bit, factory gate prices continued their now close to 3-year decline, while the GDP deflator remained underwater for the 9th quarter in a row, pointing to continued anemic household consumption. Industrial profits rebounded in August, but this recovery was uneven across different sectors and in some measure a statistical artifact. Fixed asset investment, on the other hand, turned negative year-on-year in late summer, reversing gains made earlier in 2025, while the prolonged slump in housing showed little sign of easing. Although China may be on track to meet the government annual economic growth target of “around 5%,” this achievement rests on the increasingly tenuous twin foundations of maintaining high levels of investment to grow industrial output and exporting large volumes of that output.

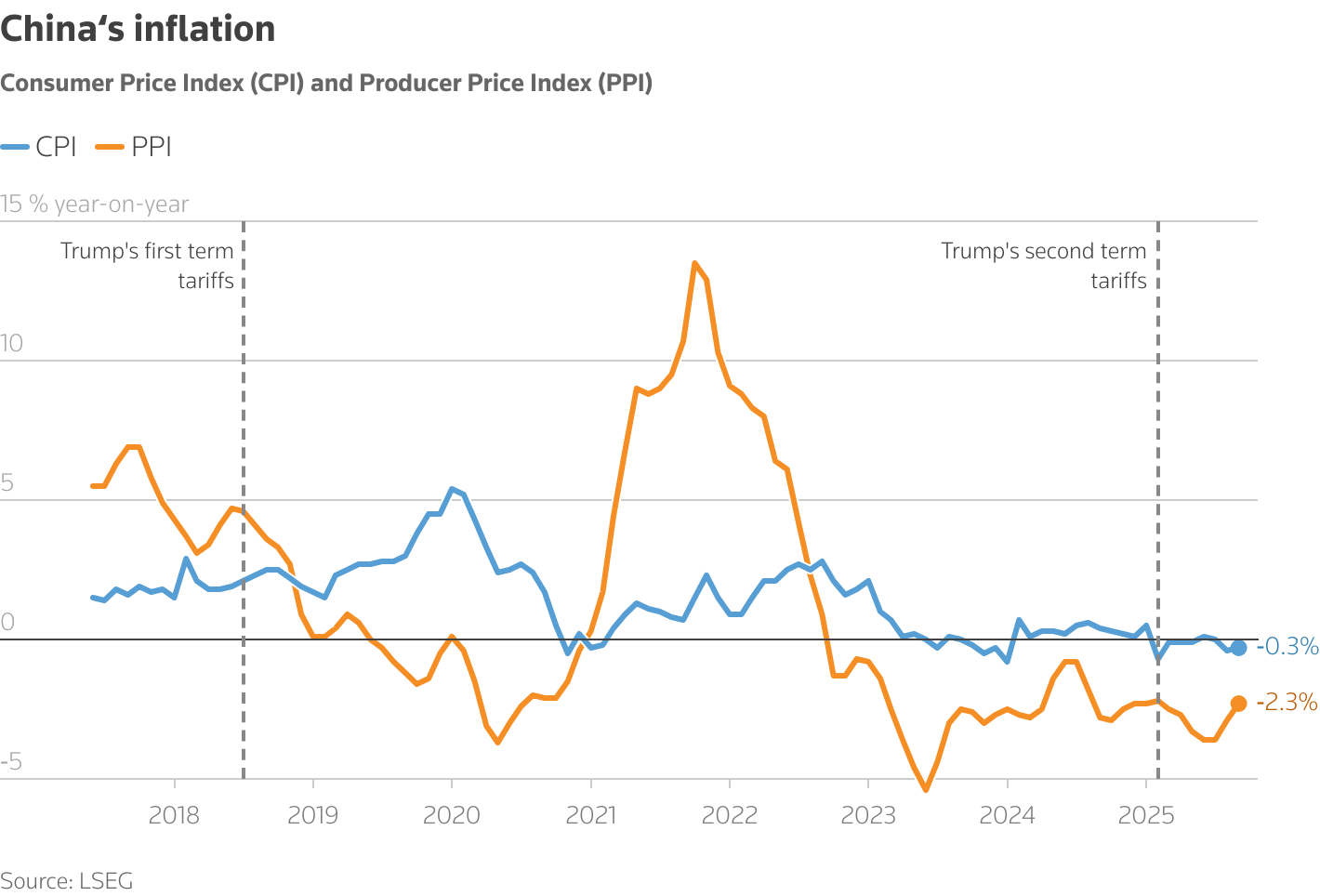

One little piece of late summer good news for the Chinese economy was a modest lessening of deflation. Factory gate prices, as measured by the producer price index (PPI), fell 2.9% from the previous year in August and then dropped another 2.3% in September compared to the previous year. Those declines were lower than the 3.6% year-on-year decrease in July. Although the latest PPI numbers come as good news, they also mark close to the third straight year in which the PPI has fallen (this trend began in October 2023). The consumer price index (CPI) dipped 0.3% in September from a year earlier, a smaller decline than the 0.4% slide in August and coming in slightly below the 0.2% drop forecasted in a Reuters poll of economists. Thus, despite these modestly encouraging data points, Huang Zichun, China economist at Capital Economics, observes,[1] “We continue to expect both CPI and PPI to stay in deflation this year and next.”

Digging a bit deeper into the August CPI data[2] reveals a mixed picture regarding recent trends in consumer prices. Core inflation, which excludes highly volatile food and fuel prices, actually rose 0.9% in August from a year earlier, the biggest jump since February. One area of strength was household appliances and clothing, which saw price increases of 4.6% and 1.9%, respectively. However, deflation in consumer durables, a key yardstick for measuring cost trends, sank to 3.7% in August, compared to 3.5% in June, as calculated by Zichun Huang, who observes that this level of deflation exceeded that of the 2008 financial crisis.

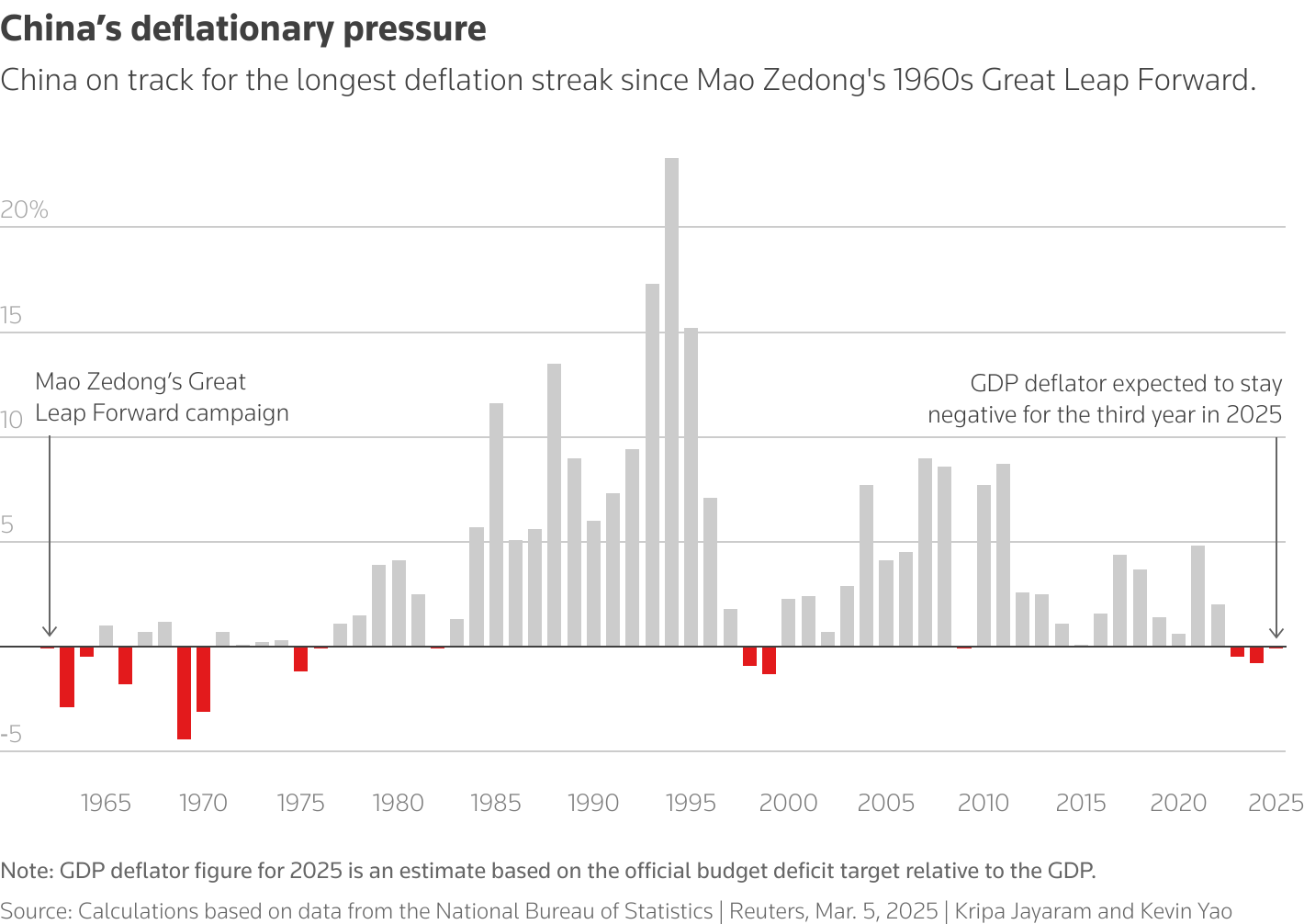

Another sign that the threat of deflation continues to stalk China’s economy is the late summer data on its GDP deflator. The deflator provides the broadest measure of prices across goods and services and came in at -1.3% during the third quarter of this year.[3] This fall marked the 9th straight quarter in which the deflator had been underwater. The GDP deflator is predicted this year to sink by at least 0.1%,[4] putting it underwater for three years running, the longest such streak since Mao’s disastrous Great Leap Forward in the early 1960s. To be sure, the 2025 figure would be a marked improvement over the 0.8% fall over last year, but it is much lower than the 2.4% boost put predicted in Premier Li Qiang’s 2024 government work report presented to the National People’s Congress.

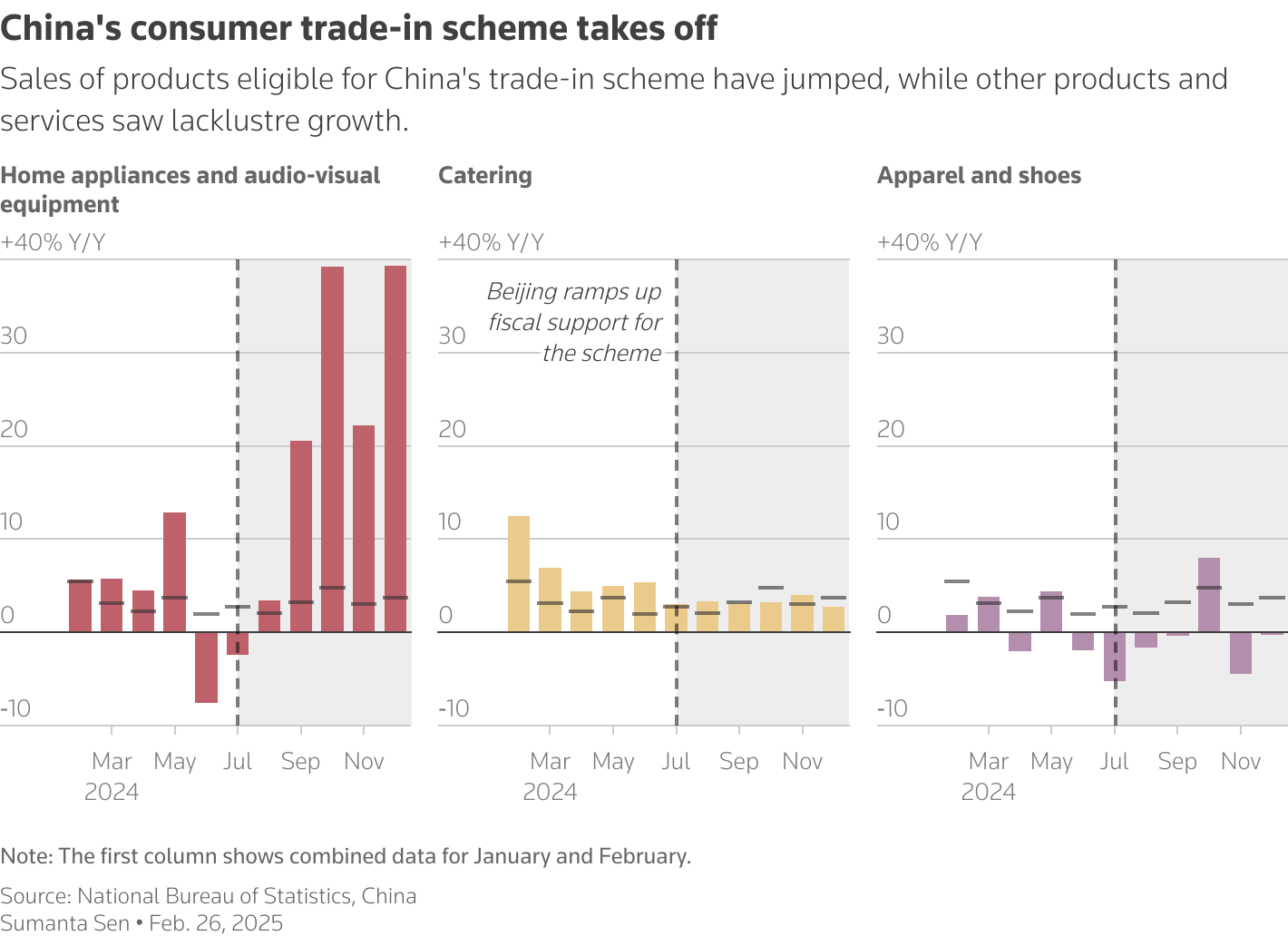

The subdued inflation numbers are indicative of sluggish Chinese consumer demand, as reflected in retail sales. The growth of retail sales slowed to 3.4% in August[5] and 3.0% in September,[6] after rising at a 3.7% and 6.8% clip in July and June, respectively. The sharp September and August deceleration in retail sales marked the weakest growth in consumer demand in 9 months, since November of 2024 (see the “retail sales slow, industrial output quickens” graph below). The September slowdown in retail sales came on the heels of diminishing local government support[7] to the trade-in subsidies for households to replace older with new consumer durable goods (I will return to this matter later in the post). For example, home appliance sales rose by just 3.3% during September, compared to a 25.3% jump during the first three quarters of this year.

A close inspection of the August consumption numbers—we have yet to see a detailed breakdown in the September consumption figures—reveals two interesting data points.[8] First, the growth in consumption was highest outside of the cities, where retail sales rose 4.6% in August from a year earlier; however, just over a third, 34.5%,[9] of Chinese now reside in countryside, so the increase in rural spending on goods could not offset the slower pace of urban consumption. A second consumption bright spot in the August data was the growth in the demand for services. According to Zhang Yuhan, principal economist at the Conference Board’s China Center, this trend was driven by leisure and travel, reflecting a growing preference among Chinese for experiences over acquiring physical goods.

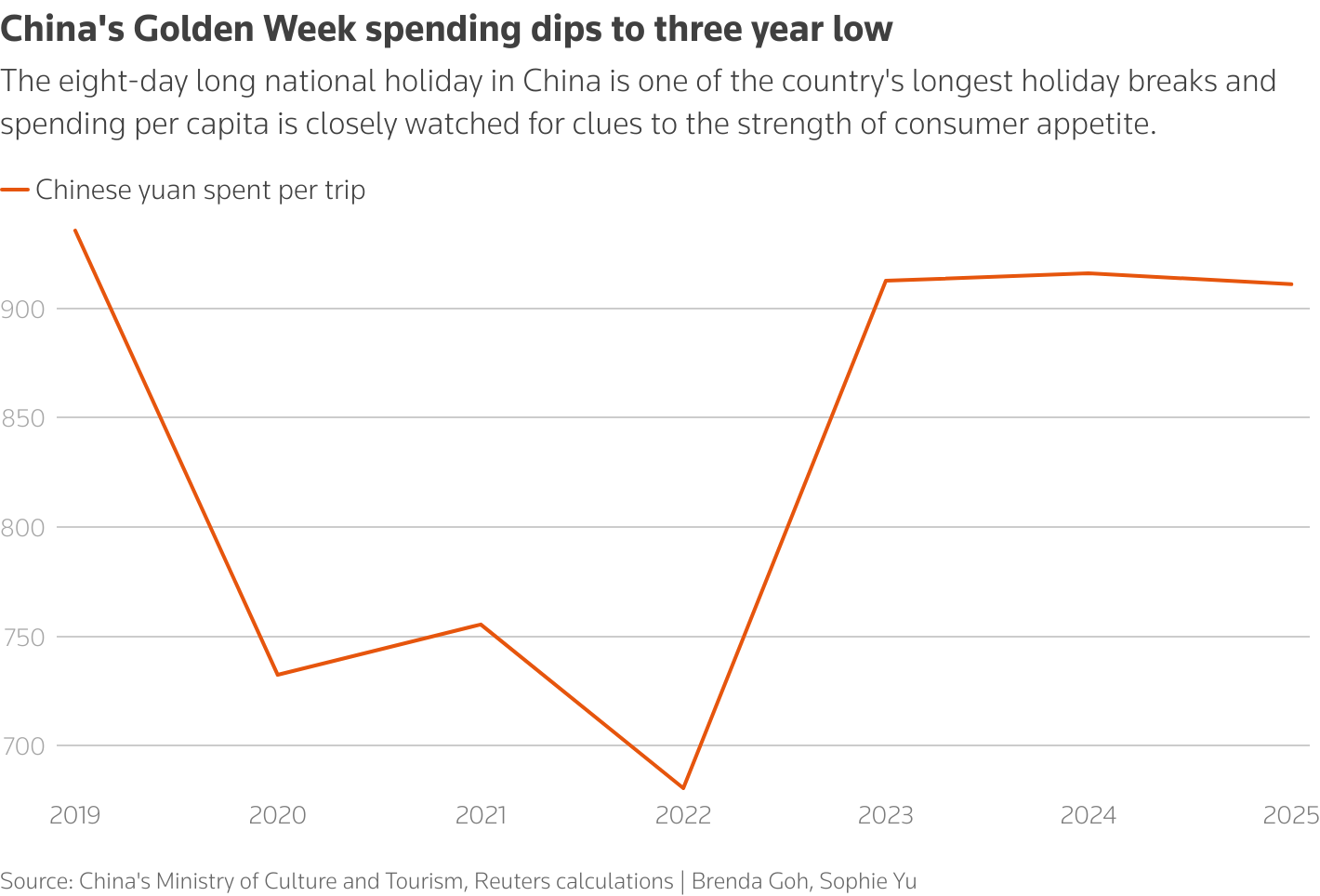

Speaking of leisure and travel, data from the recent October “Golden Week” holiday, which combined the National Day and the Mid-Autumn Festival celebrations, does not auger well for Chinese consumer spending during the 4th quarter of 2025. The number of trips Chinese made during the 2025 break totaled 888 million, compared with the 765 million trips made in 2024 (last year’s break lasted for 7 days, while this year’s break lasted 8 days). However, Reuters calculates,[10] based on Chinese Government data, that average spending per trip during the 2025 “Golden Week” was 911.04 RMB ($113.52), a 0.55% fall from the same holiday last year. That spending was the lowest since 2022. At that time, Covid-19 lockdowns significantly constrained both travel and spending while traveling. China’s hard-pressed consumers clearly remain cautious and reluctant to open their wallets.

While the growth of consumption slowed in August and September, industrial production rose sharply,[11] increasing 5.2% in August and 6.5% in September. The delta between growth of manufacturing output and retail sales had been widening since May of this year, the last time the increase in the latter exceeded that of the former. The September divergence between these trends was the biggest since last summer.

The widening gap between the amount of goods churned out by Chinese factories and the domestic demand for them is certainly a key factor contributing to deflationary pressure. It is also making China even more dependent on exports, which have long been a major driver, along with investment, in its economic growth. Confronting increasingly stagnant home consumption, firms have little choice but to expand abroad. Increasing anecdotal evidence suggests that the cut-throat price wars among manufacturers to maintain sales in the face of anemic domestic demand is showing up in the fight for foreign markets. As the sales manager of an aluminum products maker, whose firm had largely offset the loss of the US market following the Trump tariffs by exporting more to Latin America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, declared in an October 20th Reuters article,[12] “You have to be ruthlessly competitive on price … if your price is $100 and the customer starts bargaining, it’s better to drop it $10-20 and take the order. You can’t hesitate.”

Despite all of this, industrial profits rebounded sharply in August[13]—the data on industrial profits for September has yet to come in—rising 20.4% from a year earlier, reversing three months of consecutive decline. With the August jump, industrial profits for the first eight months of 2025 grew 0.9%, compared to the 1.7% fall over the first seven months of the year. Before anyone gets too carried away by this good news, two qualifications are in order. First, the August year-on-year upward spike in industrial profits reflects the low base from last August, when profitability fell by double digits. Second, the recovery in corporate earnings was highly uneven across different sectors and types of firms. Upstream industries extracting raw materials and producing nonferrous metals had the biggest rises in profits, while those in auto manufacturing, chemical products, and textiles continued to fall, dropping 0.3%, 5.5%, and 7%, respectively. State-owned enterprises had a 50% surge in profits year-on-year, vs. a 13.2% profit increase for privately owned enterprises in August.

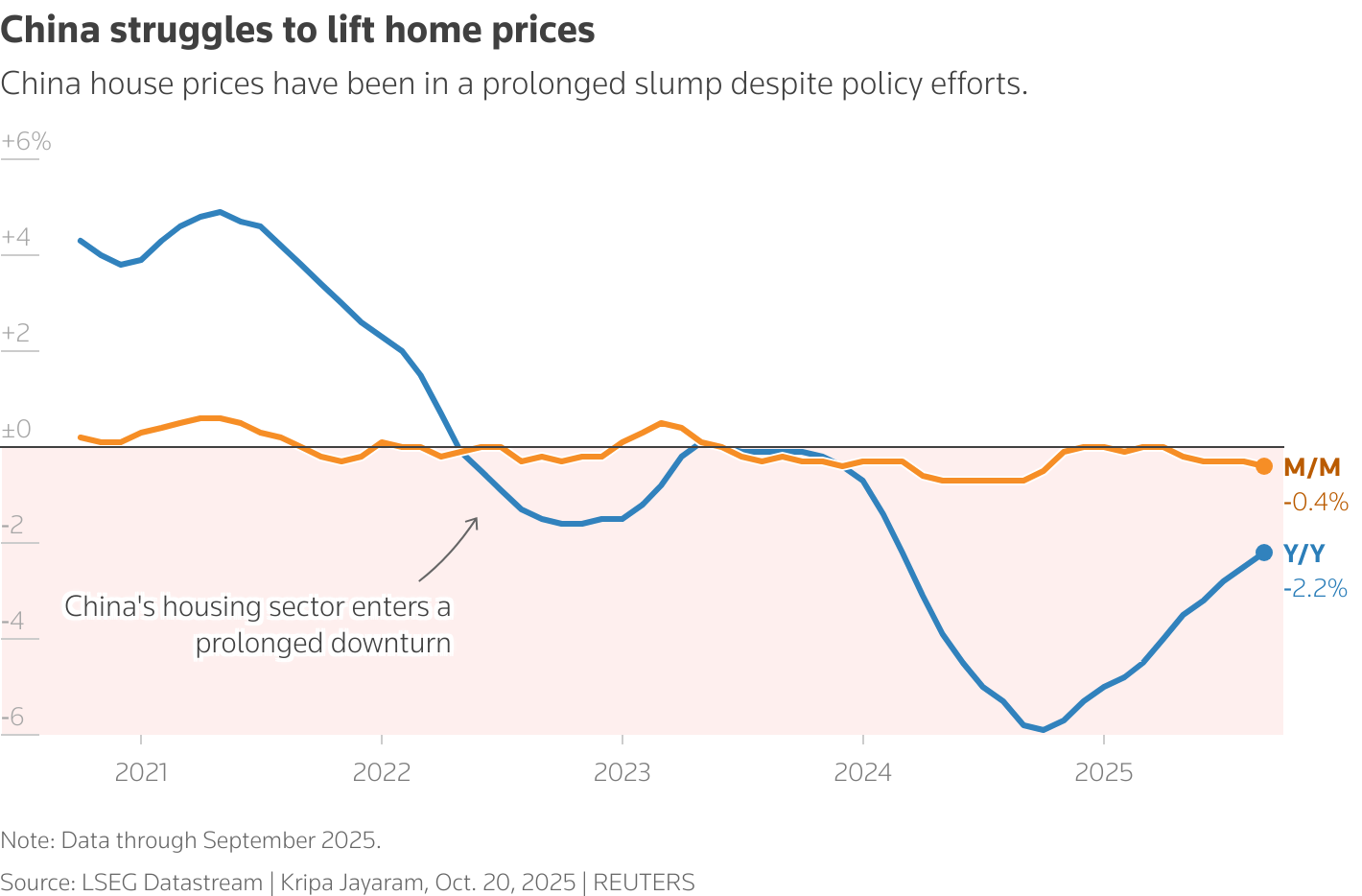

While industrial profits went back into the black during the first eight months of 2025, fixed asset investment fell unexpectedly, contracting 0.5% during the first nine months of the year,[14] coming in below the 0.1% expansion forecasted by Reuters. One factor driving this trend was a slowdown in spending on infrastructure and manufacturing. But the biggest contributor to the negative investment number was property investment, which tumbled 13.9% in 2025 through September, exceeding the 12.9% fall during the first eight months of the year.

The sharp downturn in property investment underscored the ongoing woes of China’s real estate sector. The price of new homes fell at their fastest pace in 11 months during September. Reuters calculations[15] based on China National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) data show that new home prices dropped 0.4% month-on-month in September, after dipping 0.3% in August.

Of the 70 cities surveyed by the NBS, 63 reported month-on-month declines in housing prices, with 61 showing year-on-year contractions. This downward trend extended even to the first-tier cities,[16] which have been less affected by the real estate meltdown. Shenzhen, China’s high-tech hub, recorded a 1% drop in housing prices, its steepest monthly fall since last September (lower tier cities saw largest price reductions). Finally, pre-owned homes and the secondary housing market[17] also saw prices slide in September. Prices of the former contracted 0.6% month-on-month, while the latter housing market, comprising second residences owned by such individuals, such as vacation properties, fell across all of the cities in the NBS survey, for the first time this year.

The latest stage in China’s years long real estate slump is notable for two reasons. The first is that it got worse in September—that month, along with October, is typically the peak time of the year for property buying as developers initiate sales campaigns to lure in customers during the National Day holiday. Second, the price contractions occurred even as home sales modestly ticked up.[18] These trends indicate that real estate firms and owners of pre-existing flats and villas are resorting selling properties at low, or even fire sale prices, to unload these homes, getting less than they initially asked for and taking a loss on the sale. The ruthless price-cutting to obtain sales, or, as the Chinese Government likes to call it, “involution” (内卷化 [Nèi juǎn huà]), may be infecting the housing industry.

China’s real estate crisis deepened in August and September despite continued government efforts to bolster home prices. These measures have included mortgage rate cuts, moves to accelerate urban village redevelopment, and the easing of restrictions on buying additional homes and flats by local authorities. Save for high-end luxury projects in prime locations in Tier 1 cities,[19] which performed robustly earlier this summer, nothing the government has done has moved the needle up. The basic problem is the persisting large gap between the supply of housing, which grew rapidly prior to the 2021 bursting of the real estate bubble, and demand for it. This imbalance is especially acute in the lowest tier cities (Tiers 3-5), where a large share of the population resides and which are massively overbuilt;[20] housing prices in these metropolises may never rebound to 2021 levels. As Alicia Herroro Garcia, chief economist for Asia Pacific at the French Investment Bank Natixis, said of housing in China back in the summer of 2024, “They’ve tried it all—to be frank, it (real estate) is just a bloated sector. It’s too big.”

The ongoing slump in home prices will further depress consumption by Chinese households. “If the value of real estate, especially in the first-tier cities, continues to shrink,” notes Hannah Liu,[21] China economist at Nomura Securities, “people will feel they have less money to spend and will expect even less in the future.”

Judging from the latest PPI and profits data, Chinese government authorities have been more successful taming “involution” in manufacturing than they have in stopping the slide in home prices. During July, the government announced measures[22] aimed at strictly regulating companies engaged in price cutting and getting local governments to curtail subsidies for noncompetitive “zombie” firms (I wrote about these companies in my July 14th “Bring on the Zombie Firms” blog post). In particular, the State Council pledged to crack down on “irrational competition” among electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers by more closely monitoring costs and prices in the industry. The main impact of this move has been to encourage EV firms to turn to stealth price competition,[23] such as launching new models at lower price ranges or upgrading existing models while leaving their prices unchanged.

A more substantial government attempt to curb “involution” has occurred in another industry that is a poster child for this problem, polysilicon, a basic building block for solar panels, where China’s productive capacity is twice as great[24] total global demand for this green energy component. In late July, government regulators and firms in the industry reached a deal[25] to reduce at least 1 million metric tons of lower quality polysilicon capacity. To stabilize the industry, regulators and producers plan to set up a 50 billion RMB ($7 billion) fund to acquire and shut down nearly a third of capacity in the sector.

Although this agreement comes as welcome news, Peking University finance professor Michael Pettis emphasizes[26] that such sector-specific deals will do little to address the “involution” phenomenon across manufacturing. The problem is the government’s determination to achieve an annual 5% economic growth rate. With Chinese household consumption low and the economy being driven by investment and exports, Pettis argues that the only way to still reach that magical target while reducing capacity in particular industries is to offset that loss by boosting investment and output in other sectors. He notes that in the wake of the polysilicon pact, a critical component of the petrochemical industry is set to grow by almost 50% between now and 2028, even though the refining sector is overbuilt and profits within it are being squeezed by increasingly savage price cutting competition.

This is a microcosm of what occurred following the 2021 housing crash, when Beijing massively shifted investment away from real estate to manufacturing, particularly “new productive forces” industries it deemed as strategically important. The result, of course, was widespread “involution” in that part of the economy.

This pattern appears likely to soon repeat itself, particularly in the wake of the latest investment data, which has clearly spooked Chinese economic policymakers. In an October 19th Reuters[27] roundtable of leading China business economists, Xu Tianchen, senior economist for the Economist Intelligence Unit, Beijing, predicted that the upcoming Q4 will be “heavy in investment,” adding, “negative investment growth is not something policymakers want to see.” This view was echoed by Zhang Zhiwei, chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management, who described the downturn investment as “rare and alarming” and the impetus for the Ministry of Finance’s October 17th announcement of a 500 billion RMB investment stimulus package.

At this point, it is unclear what areas of the economy are going to be targeted for additional investment stimulus. But one likely candidate is infrastructure. Indeed, the influential economist Yu Yongding,[28] who is a member of the Chinese Academy of the Social Sciences and former member of the People’s Bank of China’s monetary policy committee, has strongly argued for a 2008-style mega stimulus aimed infrastructure (most other Chinese academic economists, it should be noted, are urging the government to boost household consumption; more on that below).

The problem with doing this is that the 2008 stimulus has already saddled China with a surfeit of overbuilt and underused infrastructure. Its high-speed rail (HSR) network, whose rapid expansion following 2008 made it the largest such network in the world, is a case in point. At the end of 2023,[29] of the 45,000 kilometers of HSR track, just 2,300, or 6% of the total, was turning a profit, while all but six of the 6 HSR corridors, all of which linked together coastal economic hubs and Beijing, were bleeding red ink.

As Chinse authorities double down on investment and addressing perceived supply-side issues in the economy, they are taking the foot off of the accelerator when it comes to boosting consumption. After stating in the earlier noted Reuters roundtable that Q4 of this will be “heavy in investment,” Xu Tianchen added that it will be “light in consumption.” The government began curtailing the popular trade-in scheme aimed at subsidizing consumer spending during the summer, with the amount of special bonds allocated to support the program falling from 300 billion to 69 billion RMB.[30] A comparison of sectors covered and not covered by this plan underscores its role in raising consumer demand and helping to fuel the late-spring through early summer surge in retail sales (for the latter, see the earlier “China’s September retail sales down, industrial output quickens” graph).

The scaling back of demand stimulus reflects growing fiscal pressures[31] faced by China’s central and local governments. During the first eight months of 2025, central government tax revenues nudged up just 0.02% from a year earlier, to 12.1 trillion RMB. At the same time, local government income from selling land, a key source of revenue, fell 4.7% to 1.9 trillion RMB; in August alone, money from land sales dropped 5.8% from a year earlier.

In the face on ongoing sluggish domestic consumption and lack of government action to stimulate demand, China will fall back on its old playbook of exporting the surplus capacity caused by efforts to increase manufacturing investment and output. Chinese exports have remained robust in the face of Trump’s tariffs,[32] which reduced sales of goods sent to the US by 27% year-on-year in September. China successfully diversified its export trade, with deliveries to the European Union, Southeast Asia, and Africa rising by 14%, 15.6%, and 56.4%, respectively.

Given the weakness of domestic consumer demand and fixed asset investment, this strong export performance certainly underpinned the latest main piece of good economic news for China, namely its Q3 GDP growth. During this period, the economy is estimated to have expanded by 4.8%, leading Alex Loo, FX and macro strategist at TD Securities, Singapore, to declare in the Reuters roundtable of China business economists noted earlier, “It is likely that Beijing will meet its growth target for 2025 of ‘around 5%.’”

Attaining this goal could be seen as a decidedly mixed blessing. Loo notes that given the latest GDP growth numbers, Beijing will see “little need for more fiscal stimulus at this juncture.” However, with deflationary pressures persisting and consumer demand remaining anemic, China badly needs more fiscal stimulus directed at the demand side of its economy.

Moreover, the short-term success in maintaining desired levels of GDP growth will incentivize the government to kick the can down the road when it comes to the difficult task of making household consumption, rather than investment and exports, the main driver of GDP growth. In an October 19th post on X, Michael Pettis observed, “China’s stimulus continues to be directed to support the supply side of the economy, even as nearly everyone in China—from leading economists to newspapers to policymakers—acknowledge that it is the demand side that needs urgently to be supported. It is just too hard to do.”

But while sticking to the old playbook of investment- and export-led growth is the easier policy-making path forward, it is unsustainable over the long-term. Continued supply-side support through heavy investment to sustain and increase manufacturing output will only increase the severity and extent of “involution” problems across industry.

Nor will it be possible to China to continue exporting its way out of such problems. As noted earlier, the savage price cutting characteristic of domestic “involution” is now being practiced by exporting firms. Commenting on this, Alicia Garcia-Herrero says,[33] “I read it as ‘we need to cut prices but we are going to export in this deflationary environment because China has to export no matter what the tariffs are.’” This predatory hyper mercantilism in trade will inevitably lead to a foreign trade backlash and limit China’s ability to maintain current export volumes. Fortunately, for now at least for China, the Trump Administration is bent on punishing American allies with high tariffs rather than allying with them to combat Chinese trade practices.

As Herbert Stein, who served as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisors for Richard Nixon famously quipped in 1986, “If something cannot go on forever, it will stop.”

[1]. “Deflationary Pressure Persists in China on Weak Demand, Overcapacity,” Reuters, October 15, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinas-annual-consumer-producer-prices-remain-negative-september-2025-10-15/#:~:text=Producer%20prices%20(PPI)%20in%20September,forecasts%20in%20a%20Reuters%20poll.

[2]. Anniek Bao, “China’s Consumer Prices fall more than Expected in August as Deflation Woes Persist,” CNBC, September 9, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/09/10/china-cpi-august-deflation-.html.

[3] “China Economic Monitor, Issue: 2025 Q3,” KPMG.CON/CN, August 2025. URL: https://assets.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/cn/pdf/en/2025/08/china-economic-monitor-q3-2025.pdf.

[4]. “More Words than Deeds from China on Consumption Keep Deflation in Play,” Reuters, March 5, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/more-words-than-deeds-china-consumption-keep-deflation-play-2025-03-06/.

[5]. Jeremy Mark, “China’s Economy Remains Trapped in the Doldrums,” Atlantic Council, September 18, 2025. URL: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/blogs/econographics/chinas-economy-remains-trapped-in-the-doldrums/.

[6]. Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Economy Grows 4.8% in the Third Quarter as Expected, but Investment sees a ‘Rare and Alarming’ Drop,” CNBC, October 20, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/20/china-economic-growth-gdp-september-third-quarter-q3-retail-sales-industrial-output-urban-investment-fixed-income.html.

[7]. Anniek Bao and Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Economic Slowdown Deepens in August with Retail Sales, Industrial Output Missing Expectations,” CNBC, September 15, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/09/15/china-retail-sales-industrial-output-slow-in-august-missing-estimates-as-real-estate-slump-worsens.html.

[8]. Anniek Bao and Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Economic Slowdown Deepens in August with Retail Sales, Industrial Output Missing Expectations,” CNBC, September 15, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/09/15/china-retail-sales-industrial-output-slow-in-august-missing-estimates-as-real-estate-slump-worsens.html.

[9]. “China—Rural Population,” Trading Economics, No Date. URL: https://tradingeconomics.com/china/rural-population-percent-of-total-population-wb-data.html.

[10]. Sophie Yu and Brenda Goh, “China’s Golden Week Holiday Spending Dips in Latest Red Flag for Economy,” Reuters, October 9, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-says-114-billion-spent-during-golden-week-period-with-888-million-trips-2025-10-09/.

[11]. Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Economy Grows 4.8% in the Third Quarter as Expected, but Investment sees a ‘Rare and Alarming’ Drop,” CNBC, October 20, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/20/china-economic-growth-gdp-september-third-quarter-q3-retail-sales-industrial-output-urban-investment-fixed-income.html.

[12]. Kevin Yao and Ellen Zhang, “China’s Economy Slows as Trade War, Weak Demand Highlight Structural Risks,” Reuters, October 20, 2025: URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-q3-gdp-growth-slows-lowest-year-backs-calls-more-stimulus-2025-10-20/#:~:text=While%20industrial%20output%20grew%20to,in%2011%20months%20in%20September.

[13]. Anniek Bao, “China’s Industrial Profits Rebounded Sharply in August. Here’s What Powered that Growth,” CNBC, https://www.cnbc.com/2025/09/29/china-industrial-profit-august-rebound.html.

[14]. Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Economy Grows 4.8% in the Third Quarter as Expected, but Investment sees a ‘Rare and Alarming’ Drop,” CNBC, October 20, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/10/20/china-economic-growth-gdp-september-third-quarter-q3-retail-sales-industrial-output-urban-investment-fixed-income.html.

[15]. “China’s New Home Prices Fall at Fastest Pace in 11 Months,” Reuters, October 20, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-new-home-prices-fall-fastest-pace-11-months-2025-10-20/.

[16]. Salina Li, “China’s New Home Prices Slump at Fastest Pace in 11 Months amid Dented Buyer Confidence,” South China Morning Post, October 20, 2025. URL: https://www.scmp.com/business/article/3329662/chinas-new-home-prices-slump-fastest-pace-11-months-amid-dented-buyer-confidence.

[17]. “China Property Sales Rise, but Prices Slide in September,” China Economic News, Substack, October 21, 2025. URL: https://chinaeconomicreview.com/china-property-sales-rise-but-prices-slide-in-september/.

[18]. “China Property Sales Rise, but Prices Slide in September,” China Economic News, Substack, October 21, 2025. URL: https://chinaeconomicreview.com/china-property-sales-rise-but-prices-slide-in-september/.

[19]. “China Property Market’s Polarised Performance Leaves Risks Elevated,” Fitch Wire, August 5, 2025. URL: https://www.fitchratings.com/research/corporate-finance/china-property-markets-polarised-performance-leaves-risks-elevated-05-08-2025.

[20]. Kenneth Rogoff and Yang Yuanchen, “A Tale of Tier 3 Cities,” IMF Working Paper WP/22/196, September 2022. URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/09/29/A-Tale-of-Tier-3-Cities-524064.

[21]. “China’s New Home Prices Fall at Fastest Pace in 11 Months,” Reuters, October 20, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-new-home-prices-fall-fastest-pace-11-months-2025-10-20/.

[22]. Daisuke Wakabayashi, “China has a Problem: There’s too much Competition. The Chinese Government is Taking Steps to Rein in what it calls ‘Involution,” or Excessive Competition that is Hurting Local Companies and Fueling an Inflationary Spiral,” New York Times, July 22, 2025. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/07/22/business/china-involution-competition-deflation.html?campaign_id=2&emc=edit_th_20250723&instance_id=159041&nl=today%27s-headlines®i_id=57626452&segment_id=202426&user_id=3ba1b8d7b8a01907ae51c1b256a65253.

[23]. John Liu and Haicen Vang, “China Electric Cars on Going Global. A Cut-Throat Competition at Home Could Kill off many of its Brands,” CNN, September 29, 2025. URL: https://edition.cnn.com/2025/09/26/cars/chinese-electric-cars-price-wars-intl-hnk-dst.

[24]. Bill Spindle, “Data Dive: Chinese Solar Panel Manufacturing Output Outpaces Global Demand,” Cipher, URL: https://www.ciphernews.com/articles/chinese-solar-panel-manufacturing-outpaces-global-demand/#:~:text=The%20gap%20between%20how%20many,its%20own%20solar%20installation%20targets.

[25]. Colleen Howe, “Exclusive: China Polysilicon Firms Plan $7 Billion Fund to Shut a Third of Industrial Capacity,” Reuters, August 1, 2025. August 1, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/climate-energy/china-polysilicon-firms-plan-7-billion-fund-shut-third-industry-capacity-2025-07-31/.

[26]. Michael Pettis, “What’s New about Involution?” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Beijing, August 26, 2025. URL: https://carnegieendowment.org/posts/2025/08/whats-new-about-involution?lang=en.

[27]. “Instant View: China Q3 GDP Growth Slows to 4.8% Y/Y, in Line with Forecasts,” Reuters, October 19, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/business/finance/view-china-q3-gdp-growth-slows-48-yy-line-with-forecast-2025-10-20/.

[28]. “China Urged to Weigh 2008-Style Mega Stimulus by Ex-POBOC Advisor,” Bloomberg, October 26, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-10-27/ex-pboc-adviser-makes-outlier-call-for-2008-style-mega-stimulus.

[29]. Jeff Pao, “China’s Fast-Growing High-Speed Railway Network Faces Reality,” Asia Times, June 17, 2025. URL: https://asiatimes.com/2025/06/chinas-fast-growing-high-speed-railway-network-faces-reality/#:~:text=The%20article%20pointed%20out%20that%20China’s%20high%2Dspeed,only%20six%20in%20coastal%20cities%20are%20profitable.

[30]. “China January-June Fiscal Revenue Dips, Expenditures Rise Slows Down,” Reuters, July 25, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/china-january-june-fiscal-revenue-dips-expenditure-rise-slows-down-2025-07-25/.

[31]. “Chinese Fiscal Spending Slowdown Persist in Risk for Growth,” Bloomberg, September 17, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-09-17/chinese-fiscal-spending-slowdown-persists-in-risk-for-economy.

[32]. Kevin Yao and Ellen Zhang, “China’s Economy Slows as Trade War, Weak Demand Highlight Structural Risks,” Reuters, October 20, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-q3-gdp-growth-slows-lowest-year-backs-calls-more-stimulus-2025-10-20/#:~:text=While%20industrial%20output%20grew%20to,in%2011%20months%20in%20September.

[33]. “More Words than Deeds from China on Consumption keep Deflation in Play,” Reuters, March 5, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/more-words-than-deeds-china-consumption-keep-deflation-play-2025-03-06/.