From China Dream to Nightmare for College Educated Chinese Youth:

Chinese children have long made the following compact while growing up. They bury their heads in their books and study like crazy from a very early age up through high school to get ahead in China’s ultracompetitive education system, causing them to miss out on the fun and play of a normal childhood. By making this sacrifice, these kids can gain admission into a top-flight university and obtain stable and remunerative white-collar jobs, thereby avoiding the drudgery and insecurity of blue-collar work or a life of grinding poverty in rural villages. Unfortunately, in recent years, particularly after the Covid Pandemic, this compact has broken down.

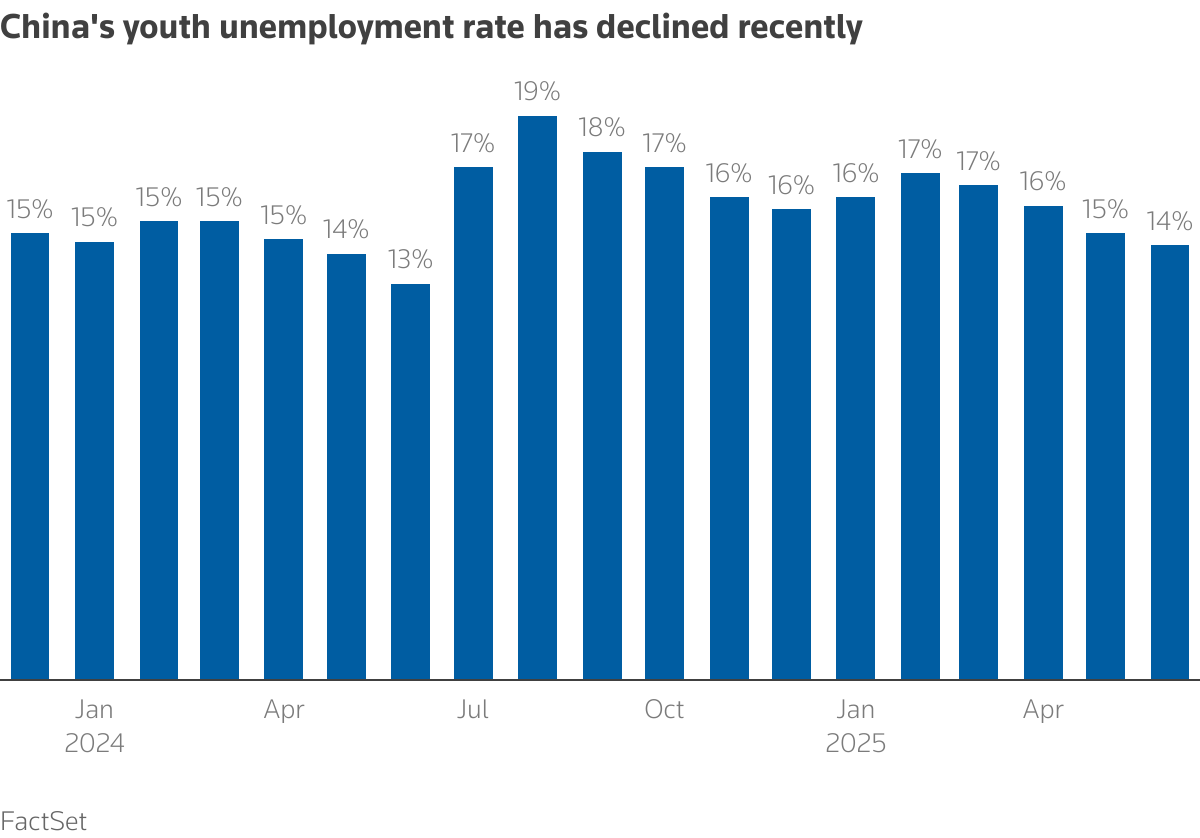

The jobless rate among urban Chinese aged 16-24 rose sharply this summer, reaching 17.8% in July[1] (the August data has yet to be released). The July figure was the highest since August 2024 and was well above the 14% youth unemployment level for June.

After the unemployment rate for 16-24 year old young people living in cities hit a record 21.3% in the middle of 2023,[2] China’s National Bureau of Statistics temporarily stopped publishing such data. When it renewed putting out these numbers some months later, jobless rates were determined using a different formula, resulting in lower youth unemployment. The revised data[3] reveals a roller-coaster pattern in youth joblessness, which averaged 14.6% in the first half of 2024 before rising to an average of 17.1% in the second half of that year. The average rate for the first half of 2025, prior to the July jump in youth unemployment, was 15.8%, or somewhat higher than during the first half of 2024.

The July upward spike in youth unemployment is particularly bad news for the record 12.2 million university graduates[4] who began looking for work this summer. All through the post-pandemic period, young Chinese college degree holders have struggled to find good jobs, resulting in intense competition for white-collar positions requiring higher education. In April, the China National Nuclear Corporation, one of the largest Chinese state-owned enterprises and a stable employer, boasted about the crush of applicants[5] after announcing job openings in the company, “We received 1,196,273 resumes! They came from 10 cities and 14 top universities across China. Together with over 100 affiliated organizations, we are hiring 1,730 key roles.” These comments provoked a huge online backlash. Chinese social media is replete with stories about highly educated youth taking jobs[6] as handymen, cleaners, food delivery drives, restaurant waiters, and even film extras.

As Northwestern University economist Nancy Qian has emphasized,[7] one major culprit for the recent struggles of college-educated job seekers is post-Covid Chinese Government economic policy decisions. Starting in 2021, Beijing initiated a regulatory crackdown to rein in Big Tech firms involving stringent capital and anti-trust rules. These moves paralleled shifting government attitudes vis-a-via foreign investment and free market economic reform. The policy uncertainty stemming from such actions, combined with the lingering impact of the Covid 19 economic shock and real estate meltdown, led property, financial, and tech companies, to sharply cut costs and jobs, curtailing high-wage, high-skilled employment opportunities for college degree holdes in these sectors.

A particularly egregious case of this was the sudden 2021 government shutdown of the burgeoning coaching busines for pimary and secondary schoolchildren. In a well-intentioned effort to ease the pressure on young children and get them to spend less time studying and more time on the playground, authorities abruptly banned online tutoring, which had been a major employment outlet for university graduates. As Qian observes,[8] “all the policy did was drastically reduce the value and the number of jobs in tech (and in the parts of the financial sector that had invested in it).” In a belated recogniton of this policy fiasco, Beijing moved last year to quietly revive the private tutoring industry;[9] however, employment in these firms remains well below its pre-2021 peak.

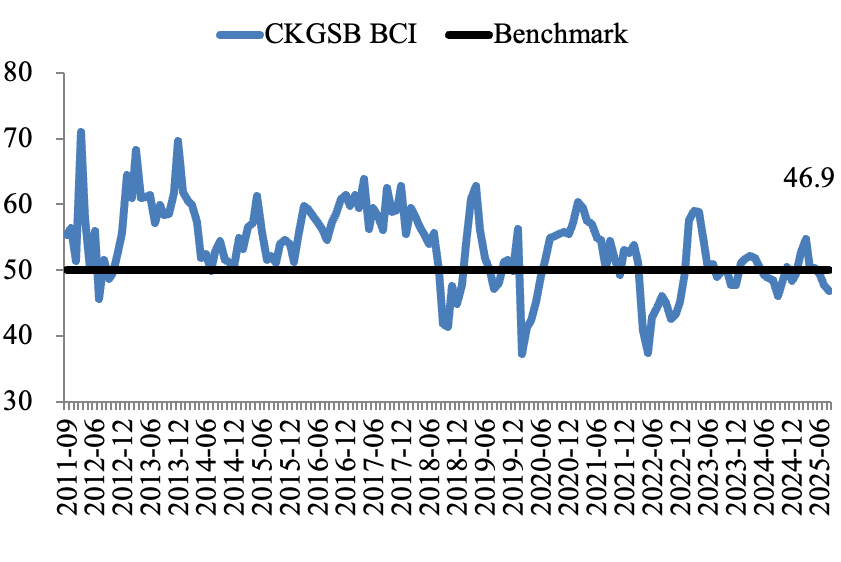

The immediate and short-term future outlook for college educated Chinese remains grim. Chinese industrial profits fell by 1.8%[10] year-on-year in the first half of 2025. July saw these profits dip a further 1.5%[11] from the previous year. Another barometer of China’s economic activity, the highly regarded Cheung Kong Graduate School of Business (CKGSB) Business Climate Index (BCI), which tracks the outlook among private enterprises, has been below 50 all through 2025, indicating lack of expansion.

The latest Reuters economists poll[12] sees GDP expansion slowing to 4.5% during the third quarter and 4.0% for the fourth quarter of this year. As Zichun Huang, China Economist at Capital Economics, notes, “We see little reason to expect much of an economic recovery during the rest of this year.” Finally, another CKGSB survey[13] conducted in September found that sentiment toward hiring among private sector employers was the weakest since 2020, when the Covid 19 pandemic began. None of this bodes well for the future employment prospects of university graduates.

A deep dive into the job-hunting travails of China’s college degree holders that appeared in China News Asia (CNA).com[14] points to two other factors further complicating the efforts of these young people to find work. One is the mismatch between their degrees and education they received while in college; the other is unrealistic expectations they bring to work. The vast majority of recent university graduates studied for corporate managerial careers in administration, strategic planning, finance, and marketing, or focused on IT-related fields. However, as was noted above, the post-Covid economic slowdown and government policies have substantially diminished employment opportunities in these areas. The problem, notes Zhao Litao, a senior research fellow at the National University of Singapore’s East Asia Institute, is that “There just aren’t enough high-quality jobs.” In the new, increasingly cutthroat competition of jobs, graduates from lower-tier institutions, where curriculum and instruction are typically outdated, have had an especially hard time finding work. On that top of that, many young Chinese want a better work life balance and have their weekends off—expectations that clash with the brutal 9-9-6 (9 am-9 pm, Monday-Saturday) office regimen still prevailing among most private employers. As Zhao observes, “The mismatch between available jobs and young people’s skills or aspirations is becoming increasingly pronounced.”

For the minority of lucky duckies who manage find work aligned with their college degree, life is often still no bed of roses. The majority of these individuals receive low salaries. Over half, 57.8%,[15] of last year’s college graduates earned less than 6,000 RMB a month. The ones receiving the best salaries had received STEM degrees and were employed as integrated circuit engineers, sales engineers, software quality assurance and testing engineers, big data engineers, software developers, gaming designers, semiconductor processing technicians, and project managers. These individuals received monthly salaries between 7,411 and 8,459 RMB and comprised just under a quarter, 23.2%, of last year’s college graduates. Noticeably absent from the above list are jobs in finance, marketing, sales, business management, strategic planning, and the like.

These salaries, even those at the higher end, are low in relation to the cost of living, especially housing, in China’s four first tier cities[16]—Shanghai, Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen. With the partial exception of Chengdu and Wuhan, the white-collar jobs sought by college degree holders remain concentrated in the Tier 1 metropolises, which have been less affected by the post-2021 real estate meltdown. The monthly rent for a basic vs. higher end flat in Beijing is now 7,000 RMB, in Shanghai 6,500 RMB, in Shenzhen 6,000 RMB, and 5,500 RMB in Guangzhou; this compares with 3,200 RMB a month in Xi’an. Non-housing monthly living expenses for a single person in Shanghai and Beijing amount to 4,027 RMB. Most of the highest earning college degree holders living on their own would therefore struggle to get by, while the over half of the university graduates pulling down less than 6,000 RMB a month could not afford housing.

Things are even worse for well-educated couples holding white-collar jobs seeking to have children and start a family. A February 2024 report[17] issued by the highly respected YuWa Population Research Institute noted that China is now the second most expensive country in the world to raise children. Especially hard-hit are the parents of pre-school toddlers, whose long hours at the office necessitates relying on nannies or expensive day care centers to look after their sons and daughters. Speaking of the former, adding insult to injury, Qian notes,[18] “In Shanghai and Beijing, nannies, who usually come from the countryside and often have not graduated from high school, earn 6,000 RMB per month.” As we just saw, that sum exceeds the monthly salary now being earned by over half of China’s college degree holders.

The marked deterioration in the job and career prosects of China’s college educated youth is surely a major factor behind a large recent shift in attitudes regarding socio-economic inequality in the country. From 2004-2014, a group of scholars based in the US and China, whose work was led and coordinated by Harvard University sociologist Martin King Whyte, conducted detailed surveys of Chinese views on why people get ahead or fall behind economically. During that earlier period, when the economy grew at or near a double-digit clip, survey respondents believed by wide margins that whether or not one succeeded or failed stemmed from his or her individual abilities or shortcomings. In 2023, Whyte and his fellow scholars conducted the same survey in China,[19] which yielded a very different set of findings. On this round, respondents were far less likely to chalk up the failure of people to get ahead to a lack of effort; an equal number cited structural obstacles to success, particularly unequal opportunity and absence of fairness in the economy. And in 2004, just a quarter of those surveyed disagreed with the statement, “Whether a person becomes rich or remains poor is their own responsibility.” In the 2023 survey, that figure had doubled, rising to 48%, while those who agreed with the statement, “In our country, effort is always rewarded,” fell from 62 to 28%.

The growing perception among young well-educated Chinese that the economy is rigged against them and that securing “moderate prosperity,” or 湿度繁荣 (Shìdù fánróng), much less getting rich, seems out of reach, has led many to embrace “lying flat,” 躺平 (tăng pīng).[20] As the name implies, this movement, which arose in 2021, views struggling to get ahead as futile, eschewing it in favor of just getting by and adopting a low desire and minimalist lifestyle. In 2022, an even more radical outlook, 摆烂 (bǎi làn), emerged among China’s Gen Z’ers,[21] which actively embraced worsening circumstances, rather than trying to change them for the better. “Bǎi làn” spawned a huge number of hits and extensive discussion among netizens, with a typical commentary grousing, “Hard to find a job after graduating this year? Fine, I’ll just 摆烂—stay at home and watch TV.”

Of course, “lying flat” or “letting it rot” is not an option for most youth lacking financial resources of their own and/or are unable to turn to their parents for money. Re the latter, as of 2023, an estimated 16 million Chinese in their 20s and early 30s,[22] including large numbers with college degrees, had become part of the “boomerang generation” living as “Full-Time Adult Children” with their parents, due to difficulties in finding employment.

Some other university graduates have sought less remunerative but more stable employment as government officials. Unlike high-skilled white-collar business jobs, civil service positions are not concentrated in a small handful of top tier cities but spread out across China.

A little over a year ago, I reconnected with a woman I had gotten to know while working as a corporate trainer at a subsidiary of the flagship Chinese State-Owned Enterprise oil giant, the China National Petroleum Company (中石油 [Zhōng Shíyóu]). This individual had interned at the company before moving back to her hometown, a lower tier city in Northeast China, and is now in her early 30s and married with a young daughter. My former work colleague told me that after being laid off in 2020, due to company downsizing, she took the civil service recruitment examination in 2021, adding that over 3,000 people signed up for the exam to compete for just 128 positions (her application was accepted). The monthly salary for these jobs amounted to just 2,800 RMB per month, plus five social insurance and one housing fund added on. My friend also informed me that the monthly costs of raising her daughter, who was still pre-school age at the time of her communication with me, came to almost 5,500 RMB a month.

Unfortunately, this employment safety valve for college-educated job seekers may be getting turned off, at least when it comes to local government entities. These bodies owe[23] an estimated 10 trillion RMB, or nearly $1.4 trillion, to companies and civil servants, a figure equivalent to about 7% of the Chinese GDP for 2024. Local governments are unlikely to do a lot of hiring when they have problems paying corporate vendors and the civil servants already on staff.

A recent BBC story[24] on underemployed college degree holders indicates that among the large number of these individuals, some have sought to make the best of difficult employment circumstances, viewing this adversity as an opportunity to reinvent themselves. One of them, a 29-year-old woman with a master’s degree in finance from Hong Kong University, who was unable to find a suitable position working in private equity, opted to become to a trainee in a Shanghai sports injury massage clinic. Rather regretting not working in the investment field, this young lady is enjoying her new career, despite its relatively low pay, and wants to open her own clinic in the future. Another university graduate profiled in the BBC report, a 25-year-old male, also with an master’s in finance, is using his job as a waiter in a Nanjing hot pot restaurant to gain practical knowledge on running a restaurant and then leverage that into setting up a dining establishment of his own.

Underemployed university graduates, including those seeking to or who have successfully reinvented themselves, often face criticism from family members. This is hardly surprising, given the large financial sacrifices many of their parents made to put their children through college in the expectation that they will find high-paying professional work. This has led some unemployed college degree holders to pay to simulate the white-collar office experience.[25] For a daily fee of around $4, individuals rent desks in so-called “fake offices” (假的办公室 [Jiǎde Bàngōngshì]) with WI-FI, free snacks, and even simulated interactions with phony supervisors. In the face of heightened difficulties in finding work, many unemployed college degree holders have turned to such spaces to bring structure to their day, maintain a sense of normality, and, above all, escape family pressure.

As that old adage goes, desperate times/situations call for desperate remedies.

[1]. Xinyi Wu, “China’s Youth Unemployment hits 11-month High as Army of Graduates Joins the job Hunt,” South China Morning Post, August 19, 2024. URL: https://www.scmp.com/economy/economic-indicators/article/3322347/chinas-youth-unemployment-hits-11-month-high-army-graduates-joins-job-hunt.

[2]. Barclay Bram, “Against All Odds,” Asia Society. September 11, 2025. URL: https://asiasociety.org/policy-institute/19-percent-revisited-how-youth-unemployment-has-changed-chinese-society.

[3]. Manishi Raychaudhuri, “China’s Fight Against Price Wars is an Uphill Struggle,” Reuters, August 12, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/chinas-fight-against-price-wars-is-an-uphill-battle-2025-08-12/#:~:text=The%20government%20has%20responded%20by,began%20offering%20discounts%20and%20subsidies.

[4]. Melody Chan, “’Do I Expect too Much?’ China’s Class of 2025 Faces Harsh Job Reality after Graduation,” China News Asia (CNA), July 11, 2025. URL: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/east-asia/china-graduates-2025-unemployment-crisis-5222776.

[5]. Mandy Zuo, “Chinese Nuclear Giant’s Recruitment Boast Sparks Backlash from Young Jobseekers,” South China Morning Post, April 11, 2025. URL: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3305996/chinese-nuclear-giants-recruitment-boast-sparks-backlash-young-jobseekers.

[6]. Stephen McDonell, “China’s overqualified Youth Taking Jobs as Drivers, Labourers and Film Extras,” BBC, January 3, 2025. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce8nlpy2n1lo.

[7]. Nancy Qian, “Is Chinese Youth Unemployment as Bad as it Looks?” Project Syndicate, September 25, 2023. URL: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-youth-unemployment-not-so-bad-by-nancy-qian-1-2023-09.

[8]. Nancy Qian, “Youth Unemployment and China’s Economic Future,” Project Syndicate, July 18, 2023. URL: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-youth-unemployment-economic-outlook-by-nancy-qian-1-2023-07.

[9]. Casey Hall and Laurie Chen, “China’s Private Tutoring Firms Emerge from the Shadows After Crackdown,” Reuters, October 27, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-private-tutoring-firms-emerge-shadows-after-crackdown-2024-10-28/#:~:text=Starting%20in%202021%2C%20a%20government,pressure%20on%20parents%20and%20students.

[10]. “China Total Industrial Profits,” Trading Economics, No Date. URL: https://tradingeconomics.com/china/corporate-profits#:~:text=China%20Industrial%20Profits%20Slip%201.8,the%20second%20straight%20monthly%20decline.

[11]. “China’s Industrial Profits Extend decline as Demand, Deflation Woes Take Toll,” Reuters, August 26, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/chinas-industrial-profits-extend-decline-demand-deflation-woes-take-toll-2025-08-27/.

[12]. Kevin Yao, Joe Cash, and Yukun Zhang, “China’s Factory Output, Retail Sales Growth Slump in Blow to Economy,” Reuters, August 15, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-factory-output-retail-sales-growth-slump-blow-economy-2025-08-15/.

[13]. “China’s Labor Market Distress Spreads at Worst Time for Deflation Fight,” Bloomberg, September 22, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-09-22/china-s-labor-distress-spreads-at-worst-time-for-deflation-fight.

[14]. Melody Chan, “’Do I Expect too Much?’ China’s Class of 2025 Faces Harsh Job Reality after Graduation,” China News Asia (CNA), July 11, 2025. URL: https://www.channelnewsasia.com/east-asia/china-graduates-2025-unemployment-crisis-5222776.

[15]. Lin Jing, “Over Half of China’s Graduates Last Year Earned up to USD835 a Month, Report Finds,” YiCai, July 17, 2025. URL: https://www.yicaiglobal.com/news/most-of-chinas-2024-college-graduates-earned-under-usd835-a-month-report-says#:~:text=According%20to%20a%20report%20by%20the%20MyCOS,their%20work%20and%20their%20fields%20of%20study.

[16]. Dream Zhou, “Cost of Living in China,” MSAAvisory, January 9, 2025. ULR: https://msadvisory.com/cost-of-living-in-china/.

[17] Liang Jianzhang, Huang Wenzhou, and He Yafu, “中国生育成本报告, 2024 (China’s Childbirth Cost Report, 2024),” Beijing: YuWa Population Research Institute, 2024. URL: https://file.c-ctrip.com/files/6/yuwa/0R72u12000d9cuimnBF37.pdf.

[18]. Nancy Qian, “China’s Youth Unemployment Problem,” Project Syndicate, May 25, 2023. URL: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/china-youth-unemployment-problem-by-nancy-qian-2023-05.

[19]. Scott Kennedy and Maria Mazocco, “Is it Me or the Economic System? Changing Evaluations of Economic Inequality in China,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Big Data China Analysis/Features, July 9, 2024. URL: https://bigdatachina.csis.org/is-it-me-or-the-economic-system-changing-evaluations-of-inequality-in-china/.

[20]. Christina Knight, “The Angst Behind China’s ‘Lying Flat’ Youth,” Atlantic Monthly, March 23, 2024. URL: https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2024/03/china-youth-protest-apathy/677852/.

[21]. Vincent Ni, “The Rise of ‘Bai Lan:’ Why China’s Frustrated Youth are Ready to ‘Let it Rot,’” Guardian, May 25, 2022. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/26/the-rise-of-bai-lan-why-chinas-frustrated-youth-are-ready-to-let-it-rot.

[22] Simina Mistreanu, “China’s ‘Full-Time Children’ Move Back in with Parents, Take on Chores as Good Jobs Grow Scarce,” Associated Press, September 12, 2023. URL: https://finance.yahoo.com/news/chinas-full-time-children-move-041008483.html?guccounter=1&guce_referrer=aHR0cHM6Ly93d3cuZ29vZ2xlLmNvbS8&guce_referrer_sig=AQAAAKRvIvU0yUWkPlA7wubgo3oKRIeOWg4iFmNW0XDBlOKry_GzLZ_L10g72JflOZMSaCbPBFsySGWVSh2R7-fECWblD7NpArUGHBF3sM1Poe6LO_fW41Uzrve9v5dYadKU5nwqRawxzkhxBoo2QhtSeEh-BWlxG2gwq5uQryBNenmk.

[23]. “China Mulls Helping Local Governments with $1.4 Trillion of Bills,” Bloomberg, September 10, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-09-11/china-mulls-helping-local-governments-with-1-trillion-of-bills.

[24]. Stephen McDonell, “China’s overqualified Youth Taking Jobs as Drivers, Labourers and Film Extras,” BBC, January 3, 2025. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/ce8nlpy2n1lo.

[25]. “China Reports 17.8% Youth Unemployment as Pretend Office Culture Rises,” Allwork.Space News Team, August 20, 2025. URL: https://allwork.space/2025/08/china-reports-17-8-youth-unemployment-as-pretend-office-culture-rises/.