As anyone who, as I did, spent years living in China knows, the country’s treasure trove of splendid monuments, like the Great Wall and Forbidden City, are juxtaposed against sea of things the Chinese call 假的 (Jiǎde), or “phony/fake.” The latter range from “Rolex” watches peddled by street hawkers that cease functioning within days to cheesy knockoffs of foreign UNESCO World Heritage Sites. A recent addition to this fakery is the growth of “scam” loans issued by Chinese banks. This development reflects continued weakness in the post-Covid Chinese economy.

Back in mid-November, Bloomberg[1] reported that the owner of an auto parts manufacturer in Zhejiang, one of China’s most prosperous and economically advanced provinces, received a highly unusual proposition from one of the big Chinese banks. A loan officer at the bank requested that this businessman borrow 5 million RMB ($700,000), deposit the money and repay it the next month. The bank agreed to cover the interest. After being badgered with daily calls from the bank, the businessman finally said “yes,” declaring “I didn’t want the loan at all, but ended up helping them.”

This kind of behavior did not start this year. In 2023, government regulators reported[2] that six state-owned financial institutions extended loans amounting to 516.7 billion RMB shortly before key performance evaluations, only to reclaim them immediately after the evaluations were done. Some companies were found to have re-deposited the funds in the same bank accounts or placed them in fixed deposits after receiving the loans.

However, the extent of such “quick-lend-and-recover” tactics involving issuing short-term loans, only to reclaim them weeks later, has risen markedly over the past 12 months. According to the Bloomberg story, nearly 20 bank employees interviewed by the publication attributed this trend to heightened pressure from the Chinese government, which controls nearly all of the banks in the country, to meet state-mandated lending targets. That has led banks to engage in bizarre behavior. For example, a Guandong Province businessman said he recently tried to repay a 3 million RMB loan ($420,000), but the bank requested that he delay repayment for another month so as not to prevent it from meeting its quarterly lending target. When the businessman returned to pay the following month, the bank offered him compensation equivalent to what he would have saved in interest payments from early repayment in order to keep the loan outstanding and on its loan portfolio.

Banks are in a bind because government regulator calls to boost lending, in hopes that it will stimulate a sluggish economy, come at a time when businesses and households are in no mood to borrow money. In July, new loans actually contracted,[3] marking the first time that had happened in 20 years. According to the well-regarded Chinese financial magazine, Caixin,[4] banks issued 220 billion RMB ($31 billion) in new RMB-denominated loans in October, down roughly 280 billion RMB from a year earlier (based on data from the People’s Bank of China). Total social financing, a broad measure of credit and liquidity, declined to 815 billion RMB, the weakest monthly total since August 2024 and down 597 billion RMB year-on-year. The contraction in household borrowing has been especially severe, dropping by 360.4 billion RMB in October, with short-term borrowing accounting for 286.6 billion RMB of this decline and medium- to long-term loans falling by 70 billion RMB.

Banks are thus struggling to lend money, despite aggressively easing credit[5] through lowering interest rates, sweetening loan conditions, and offering other perks, including more favorable exchange rates. They are doing this in the face of regulators urging them to avoid cutthroat competition and price wars—peddling “scam” or “phantom” loans is an extreme way of getting the upper hand over other banks in this struggle. Such behavior, or “involution” (内卷 [nèijuăn]), which has become endemic to industries like electric vehicles, is now making its way into the financial sector. And with businesses and households deleveraging rather than borrowing, efforts to ease credit to boost the economy may well, to invoke Keynes’s memorable phrase about monetary policy at the zero-interest bound, be like “pushing a string.”

In addition to aggressively deleveraging, Chinese households are reining in their consumption. Retail sales, a key measure of consumption, grew in November just 1.3%,[6] after going up 2.9% in October and 3.0% in September (all these figures are year-on-year rises). The October and September increases were the slowest since August of last year, while the November figure came in well below the 2.8% growth predicted by forecasters. The detailed review[7] of the November retail sales data by CNBC’s Anniek Bao points to two sectors where the slowdown in consumption was especially evident. One is automobiles. According to data from the China Automobile Association, November retail car sales by volume declined for the first time in three years, dropping 8.1% from a year earlier to 2.23 million vehicles, as many local governments paused trade-in subsidies. Major online shopping platforms also saw disappointing sales performance, even after the “Singles’ Day” sale period, one of China’s biggest shopping periods, was extended from mid-October through to November 11, making it the longest such period ever. Gross merchandise sales volume grew by just 12% vs. the 20% rise during the previous year.

Manufacturing output also decelerated in November,[8] but at a much slower rate than retail sales. Industrial production increased 4.8% year-on-year after going up 4.9% in October, the weakest pace since August 2024 and missing the 5% growth forecasted in a Reuters poll. The sharp slump in retail sales caused the delta between it and industrial production to further widen in November.

The increased gap between what Chinese manufacturers produce and what Chinese consumers consume have left the former even more dependent on export sales, causing China’s trade surplus to balloon to over $1 trillion. Interestingly, China’s rising trade surpluses are more reflective of rises in export volumes vs. the value of these exports. Indeed, according to China’s General Administration of Customs, the value of Chinese exports dipped 1.1%[9] in October compared to a year earlier.

This unexpected development shows that the cut-throat price rivalry among manufacturers in the domestic Chinese market has made its way into competition for export markets. As the sales manager of an aluminum products maker, whose firm had largely offset the loss of the US market following the Trump tariffs by exporting more to Latin America, Africa, Southeast Asia, and the Middle East, declared in a Reuters article,[10] “You have to be ruthlessly competitive on price … if your price is $100 and the customer starts bargaining, it’s better to drop it $10-20 and take the order. You can’t hesitate.”

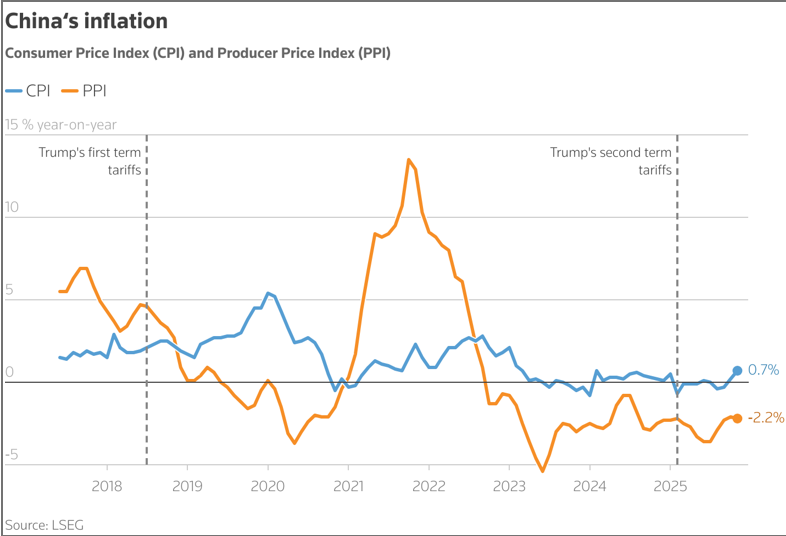

Speaking of prices, the November and October factory gate price data[11] indicates that the threat of deflation continues to loom over China’s economy. The producer price index (PPI) dropped 2.2% year-on-year in November, a slightly bigger decline than the 2.1% decrease in October. The November decrease in the PPI was worse than 2.0% drop forecasted in a Reuters poll and marked the 38th consecutive month in which it has fallen.

To be sure, China got a bit of good news with respect to the consumer price index (CPI), which edged up 0.7% from a year earlier, compared to a 0.2% rise in October and matching the expectation in a Reuters poll of economists. But lest anyone get too carried away by this green shoot, it bears noting that core inflation, which omits volatile food and fuel prices, remained the same in November compared to October. Much of the November headline CPI was driven by transitory factors,[12] such as higher prices for fresh vegetables stemming from adverse weather conditions, while a spike in gold prices prevented the core inflation from falling.

Zavier Wong, market analyst at the investment firm eToro, is therefore correct to state in Reuters,[13] “China’s latest inflation figures indicate an economy that is warming up on the surface but is still battling deep-seated deflationary pressure underneath.”

That verdict is further borne out by China’s GDP deflator, the broadest measure of prices across goods and services, that has been steadily declining for the past 10 quarters[14] and is expected to drop during the last quarter of 2025. This trend tells us that deflation is becoming entrenched in the manufacturing sector. And analysts at Morgan Stanley recently delivered more bad news to China on this front, predicting that the GDP deflator[15] will fall 0.7% in 2026 before rising 0.2% in 2027.

The prolonged deflation, driven by the combination of weak domestic consumption and savage price competition among firms to maintain sales, is hammering corporate profits. During the first half of 2025, more than 25%[16] of the listed Chinese companies reported a loss, the highest share in at least a quarter of a century. This trend accelerated during the fall, with profits of firms with annual revenues exceeding 200 million RMB falling 13.2% from a year earlier.[17] This drop came on of a 5.5% slide in October.

The downward pressure on corporate earnings is causing wages to fall and reducing job security across the economy. A November 9th Bloomberg “Big Take”[18] details the ground-level impact of deflation, while also arguing that official Chinese Government data understates deflation, especially among goods bought by ordinary people. Those affected by the deteriorating business environment range from factory workers turned street vendors all the way up to high level managers in tech firms pulling down six figure salaries (in dollars, mind you, not RMB!). Bloomberg notes that salaries and wages in private firms, who employ over 80% of the Chinese urban workforce, are growing at their slowest pace on record. In manufacturing and IT, wages declined for the first time in the official government data. Even in the flagship “new productive forces” sectors like AI and new energy, entry-level salaries are 7% below their 2022 peak. All of this comes on top of a private survey of salaries revealing that between 2022 and 2024, average pay offers in 38 cities fell 5% (this survey was discontinued last year, so data for 2025 is lacking).

Those working outside the private sector in state-owned enterprises (SOEs) and as civil servants,[19] two areas long seen as providing highly stable employment, are also being swept up by wage cuts and layoffs (disclosure alert, I spent years working as a “corporate trainer” in a flagship SOE, the China National Petroleum Company, 中石油 [Zhōng shíyóu]). In the case of the former, substantial salary reductions have extended to senior level managers in state financial institutions, including China International Capital Corporation, one of the country’s most important investment banks, who have seen their compensation cut by over 5%, while lower staff have been hit with similar pay cuts. Ordinary SOE employees are facing layoffs and for those retaining their jobs, wage cuts and delays in getting paid are becoming the norm. The situation is just as dire for civil servants. In Shandong Province, county and township government workers, including police officers, have had their salaries slashed by 30%, with payments subject to frequent delays. Law enforcement personnel elsewhere in China have experienced similar reductions, with annual pay dropping by a third, from 300,000 to 200,000 RMB.

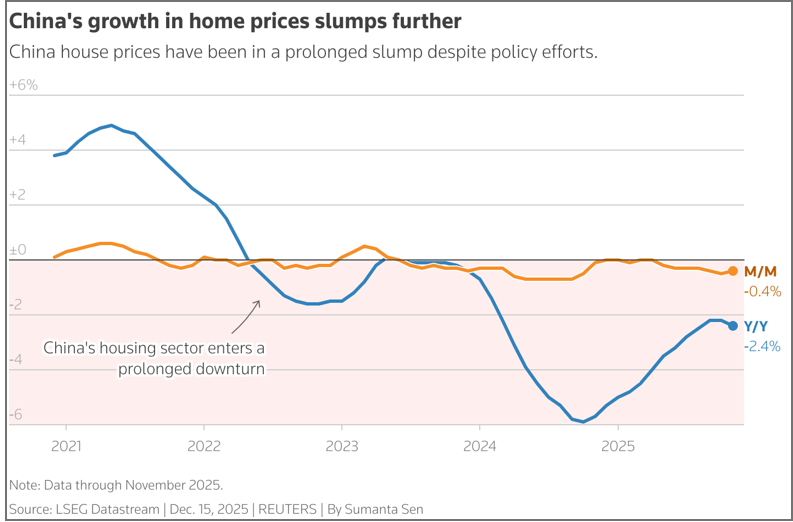

While the layoffs and wage cuts among private sector and SOE employees reflect “involution” pressures, the difficulties of local government workers stem from China’s post-2021 property meltdown. The real estate crash has greatly eroded revenue from land sales that are crucial for Chinese local government finances—China continues to refrain from levying property taxes. The most recent data on land sales revenue from the first seven months of 2025 indicates that it contracted 4.6% year-on-year.[20]

Of course, the housing slump is affecting not just the financial well-being of local government workers, but further squeezing Chinese households in general, as 70% of their wealth is tied to the apartments and villas they own. According to Barclays, over $18 trillion in household wealth has evaporated[21] following the collapse in home values starting in 2021. That sum is close to China’s current annual nominal GDP of $19.4 trillion.

Unfortunately, for China’s long suffering property owners, home prices continued their downward trend this fall. China Real Estate Information notes that during October, new home sales of the top 100 builders plunged 42% year-on-year,[22] the steepest decline in 18 months. According to calculations from Reuters,[23] home prices fell 0.4% month-on-month in November, a slight improvement from a month-on-month drop of 0.5% in October. On an annual basis, home prices contracted 2.4% in November, which was markedly higher than the 2.2% slide in October. The secondary home market also struggled across first-, second-, and third-tier cites, dropping 5.8%, 5.6%, and 5.8% respectively in these metropolises. In 2025, sales of new homes by floor area[24] decreased 7.8% from January to November, compared to a 6.8% fall from January to October.

Another strong sign of weakness in the housing sector is the woes of China Vanke,[25] the last major Chinese real estate firm to have avoided defaulting on its debts during the property crisis. This firm, whose biggest shareholder and benefactor is the Shenzhen Metro Group tied to the city of Shenzhen, China’s high-tech hub, reported losses of 28 billion RMB for the first three quarters of 2025, after posting a record loss of 49.5 billion RMB in 2024. This red ink has saddled Vanke with increasingly severe debt challenges—like all Chinese property developers, the firm is heavily leveraged—and liquidity issues, leading it to ask bondholders to negotiate a loan repayment extension to avoid default. While holders of its 2 billion RMB ($284 million) note voted to extend the payment grace period to January 28th, Vanke’s proposals to defer principal payment for 12 months failed to secure approval. The developer is also trying to persuade investors to accept delayed payment on a 3.7 billion RMB bond that matures at the end of December. With its $50 billion of interest-bearing liabilities, a Vanke default would be a major negative shock to the still shaky Chinese property market.

Vanke’s difficulties reflect the problems property developers are having in persuading investors that buyers exist for their vacant apartments, even after heavily discounting their prices. Thus, over the January-November period, property investment fell sharply, dropping 15.9%.[26] Linghui Fu, a spokesperson for China’s customs administration, told journalists that the drop in property investment largely drove the January-November 2.6% decline in overall fixed asset investment.

There is no sign that property slump will end anytime soon. Economists in the most recent Reuters quarterly poll[27] are predicting that home prices will keep falling through 2026 before things flatten out 2027. Some of the economists believe the crisis could go on even longer. They point to structural problems, such as China’s adverse demography, with its contracting cohort of people aged 20-50 who are the biggest purchasers of durable goods and housing, as well as supply gluts particularly in lower-tier cites. In the meantime, the IMF estimates that China will need to spend 5% of its GDP[28] to end the property crisis in three years.

It is little wonder then that Chinese households are deleveraging rather than borrowing and reining in consumption. While doing all of that, they are salting money away. Last year, households increased their savings to the equivalent of around 110% of China’s GDP,[29] the highest such figure ever. This behavior is not just indicative of the greater desire to save for a rainy day in the face of rising economic uncertainty, but may also reflect the expectation of lower future prices. If the latter is true, China faces serious risk of a deflationary spiral.

The latest slew of bad economic numbers has prompted government moves to maintain or even expand consumer goods trade-in subsidies. It has also prompted growing calls for more fundamental economic rebalancing involving shifting income to households to make domestic consumption, rather than exports and investment, the main economic growth driver. However, we have been to that latter rodeo many a time since Premier Wen Jiaobao’s 2007 declaration that China’s economy was “unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable” (不平衡, 不协调, 不可持续 [bù pínghéng, bù xiéxié, bù kě chíxù]). At every turn, political obstacles have blocked restructuring of the economy in favor of raising household incomes. Given the current increasingly dire economic predicament, this time may be different, but that is not at all certain.

There is one thing that is certain in the absence of fundamental economic reform. If the government attempts to hit its 5% growth target by easing credit to boost investment, there will be more pressure on financial institutions to meet higher lending targets, even as businesses and households remain reluctant or unable to borrow. Bring on the fake/phantom loans!!

Three Quick Updates/Additions:

As if more evidence of the severity of the housing crisis in China was needed, yet another sign of that came up in early December, courtesy of authorities in Shanghai. Local officials are scrubbing social media posts[30] expressing pessimism about the property market. As that old adage goes, “When the news is bad, shoot the messenger.” Well, it goes something like that!

A long Wall Street Journal[31] casts further light on why the consumption level of Chinese households is so low. This deep dive notes that China’s army of gig workers has swelled to 200 million, or one-third of the non-agricultural urban labor force. These individuals receive very little pay for long hours—delivery drivers typically put in 14-hour shifts, so even if they were paid more, when would they have time to shop? I should note that Reuters[32] did a similar long piece on the growth of gig work earlier in the year. The increased prevalence of such employment over stable middle-class jobs in offices, factories, construction, and private services constitutes one more obstacle to increasing consumption in the Chinese economy. As if that were not enough, the so-called “new productive forces” economic sectors Beijing is targeting for future economic growth are capital-intensive and are not major job creators.

Lastly, China Vanke did secure an extension of its 3.7 billion yuan note[33] that had been due on December 28th. Bondholders agreed to prolong the grace period from 5 days to 30 trading days, which give the firm more leeway to renegotiate payment. As with the 2 billion yuan note, bondholders rejected a year-long delay in paying off the principal. This development provides Vanke China with a temporary reprieve from default, but it is by no means out of the woods, with Fitch still downgrading its credit status. And while China’s troubled housing sector has been spared a major short-term shock, keeping Vanke alive on the drip life support of short-term credit risks turning it into a “zombie” firm. Having this happen would constitute another unsettling parallel between present-day China and Japan during “lost decade” of economic growth stemming from a balance sheet recession.

[1]. “China’s Banks Issue Phantom Loans to Hit Targets in Slow Economy,” Bloomberg, November 11, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2025-11-11/china-banks-issue-phantom-loans-to-hit-targets-in-slow-economy.

[2]. “Chinese Banks are Accelerating ‘Scam Loans,’ Offering Loans Quickly and Repaying them Quickly, aiming to meet Government loan targets,” Money and Banking Online, November 12, 2025. URL: https://en.moneyandbanking.co.th/2025/208104/.

[3]. “Chinese Banks are Accelerating ‘Scam Loans,’ Offering Loans Quickly and Repaying them Quickly, aiming to meet Government loan targets,” Money and Banking Online, November 12, 2025. URL: https://en.moneyandbanking.co.th/2025/208104/.

[4]. Yang Jing, “China’s Credit Growth Weakens as Households cut back Debt,” Caixin Global, November 17, 2025. URL: https://www.caixinglobal.com/2025-11-17/chinas-credit-growth-weakens-as-households-cut-back-on-debt-102383941.html.

[5]. “Chinese Banks are Accelerating ‘Scam Loans,’ Offering Loans Quickly and Repaying them Quickly, aiming to meet Government loan targets,” Money and Banking Online, November 12, 2025. URL: https://en.moneyandbanking.co.th/2025/208104/.

[6]. “China’s November Industrial Output grows 4.8% y/y, retail sales up 1.3%,” Reuters, December 14, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinas-november-industrial-output-grows-48-yy-retail-sales-up-13-2025-12-15/.

[7]. Anniek Bao, “China’s Retail Sales Growth Sharply Misses Estimates in November, Deepening Consumption Worries,” CNBC, December 14, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/12/15/chinas-november-retail-sales-industrial-production-fixed-asset-investment.html.

[8]. Joe Cash, “China’s Economy Stalls in November as Calls Grow for Reform,” Reuters, December 15, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-factory-output-retail-sales-weaken-november-2025-12-15/.

[9]. Keith Bradsher, “China’s Exports Unexpectedly Falter as Price Keep Falling,” New York Times, November 7, 2025. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2025/11/07/business/china-exports-fall.html.

[10]. Kevin Yao and Ellen Zhang, “China’s Economy Slows as Trade War, Weak Demand Highlight Structural Risks,” Reuters, October 20, 2025: URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-q3-gdp-growth-slows-lowest-year-backs-calls-more-stimulus-2025-10-20/#:~:text=While%20industrial%20output%20grew%20to,in%2011%20months%20in%20September.

[11]. “China’s Deflationary Strains Persist even as Consumer Inflation hits a 21-month high,” Reuters, December 10, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-consumer-inflation-quickens-november-producer-deflation-persists-2025-12-10/.

[12]. Anniek Bao, “China Consumer Inflation hits near two-year high, despite deeper-than-expected Producer Deflation,” CNBC, December 9, 2025. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2025/12/10/chinas-cpi-ppi-deflation-november-consumer-prices.html.

[13]. “China’s Deflationary Strains Persist even as Consumer Inflation hits a 21-month high,” Reuters, December 10, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-consumer-inflation-quickens-november-producer-deflation-persists-2025-12-10/.

[14]. “True Cost of China’s Falling Prices,” Bloomberg, November 9, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2025-china-deflation-cost/.

[15]. “China Likely to Chase 5% GDP growth in 2026 in Bid to end Deflation,” Reuters, December 3, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-likely-chase-5-gdp-growth-2026-bid-end-deflation-2025-12-03/.

[16]. “True Cost of China’s Falling Prices,” Bloomberg, November 9, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2025-china-deflation-cost/.

[17]. Edward White, “China’s industrial profits plunge as weak demand and deflation bite,” Financial Times, December 26, 2025. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/2a69ff03-5ead-4818-a5f8-2fb5f6f41e1b.

[18]. “True Cost of China’s Falling Prices,” Bloomberg, November 9, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2025-china-deflation-cost/.

[19]. Qian Lang, “Widespread Pay Cut in Cuts in China Drive down Consumer Spending, Fuel Deflationary Fears,” Radio Free Asia, June 17, 2025. URL: https://www.rfa.org/english/china/2025/06/17/china-economy-deflation-wage-cuts-layoffs/.

[20]. “China’s Government Land Sales Revenue down 4.6% Y/Y in January-July,” Reuters, August 19, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/chinas-government-land-sales-revenue-down-46-yy-january-july-2025-08-19/.

[21]. Nik Martin, “Why China’s Property Crash must be kept Top Secret,” Deutsche Welle, December 15, 2025. URL: https://www.dw.com/en/why-chinas-property-crash-must-be-kept-top-secret/a-75074157.

[22]. Nik Martin, “Why China’s Property Crash must be kept Top Secret,” Deutsche Welle, December 15, 2025. URL: https://www.dw.com/en/why-chinas-property-crash-must-be-kept-top-secret/a-75074157.

[23]. Liangping Gao and Liz Lee, “China’s Home Prices Slide Further in November,” Reuters, December 14, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinas-home-prices-slide-further-november-2025-12-15/.

[24]. Mia Nurmamat, “China’s Growth Engines Sputter as Retail and Investment Hit in November,” South China Morning Post, December 15, 2025. URL: https://www.scmp.com/economy/economic-indicators/article/3336420/chinas-consumption-and-investment-show-weak-performance-november.

[25]. “China Vanke Wins Bonderholders’ Reprieve, Averts Default for now,” South China Morning Post, December 20, 2025. URL: https://www.scmp.com/business/china-business/article/3337405/china-vanke-wins-bondholders-reprieve-averts-default-now.

[26]. Joe Cash, “China’s Economy Stalls in November as Calls Grow for Reform,” Reuters, December 15, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-factory-output-retail-sales-weaken-november-2025-12-15/.

[27]. Liangping Gao and Liz Lee, “China’s Home Prices Slide Further in November,” Reuters, December 14, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinas-home-prices-slide-further-november-2025-12-15/.

[28]. “Beijing-IMF Managing Director: China Will Need to Spend 5% of GDP to Resolve Property Crisis in next 3 Years,” Market Screener, December 10, 2025. URL: https://www.marketscreener.com/news/beijing-imf-managing-director-china-will-need-to-spend-5-of-gdp-to-resolve-property-crisis-in-next-ce7d51d3df81f521.

[29]. “True Cost of China’s Falling Prices,” Bloomberg, November 9, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2025-china-deflation-cost/.

[29]. Authorities in Shanghai are Wiping Away Social Media Posts that Express Pessimism about the Property Market,” Bloomberg, December 4, 2025. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/newsletters/2025-12-05/years-into-china-s-property-crisis-even-more-dark-clouds-gather.

[31]. Yoko Kubota, “14-hour Shift and $1 a Delivery—but China’s Army of Gig Workers Keeps Growing,” Wall Street Journal, December 20, 2025. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/asia/14-hour-shifts-and-1-a-deliverybut-chinas-army-of-gig-workers-keeps-growing-81ce58e4?gaa_at=eafs&gaa_n=AWEtsqf59zZ_6g0ZkzkLJmZPEhpV46Qg4GvPJOjyK8lEP2jFULBES1KRWUxBnJBnAcg%3D&gaa_ts=694c3bb4&gaa_sig=qvhVh8YdBp45PQ0ayXJw9oLDWN9r3A0Q1cIi4Fgbeh3u5HAmPnksaSUPKm2iIUEuNcYfPyAz82eVtHuL817yBg%3D%3D.

[32]. “Beneath China’s Resilient Economy, a Life of Pay Cuts and Side Hustles,” Reuters, July 15, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/sustainability/sustainable-finance-reporting/beneath-chinas-resilient-economy-life-pay-cuts-side-hustles-2025-07-15/#:~:text=Workers%20bear%20the%20brunt%20of,home%20as%20a%20domestic%20issue.%22.

[33]. “China Vanke Bondholders Approve Grace Period Extension, Reject Year-long Delay,” Reuters, December 26, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/china-vanke-bondholders-approve-grace-period-extension-reject-year-long-delay-2025-12-26