A Tale of two Economies on the cusp of a “Lost Decade:” How does present-day China compare with Japan in the early 1990s?

The past year is surely one that Chinese economic policymakers in Beijing are glad to have behind them. The last 12 months were marked by disappointing inflation numbers, which consistently came in below expectations, particularly in the fall, reflecting anemic consumer demand and the looming threat of deflation. At the same time, the real estate sector remained mired in crisis. As if that were not enough, it now appears that the growth of China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) over the past two years was actually well below the official Government figures. On top of that, the bond market issued a negative verdict on the Chinese economy, with long-term bond yields in China falling below those of the Japan for the first time ever.

The last data point underscores that the “Japanification” of the Chinese economy may well be underway, raising the strong likelihood that it, like its Japanese counterpart following the early 1990s, could be heading into its own “lost decade.” After quickly reviewing the consumer and factory price, real estate, GDP growth, and bond yield numbers, this blog post will do a little deeper dive into how China compares to early 1990s Japan as it stands on the cusp of a possible prolonged period of slow economic growth. In particular, I will argue that China does worse than Japan in two crucial areas, namely its demographic crunch and levels of household and government debt. China’s ability to deal with a long-term economic downturn will be further complicated by weak governmental fiscal capacity, hindering efforts to strengthen its weak social safety net in the face of a weaker economy. Finally, Chinese local, provincial, and above all national level authorities, seem unwilling to undertake the economic reforms needed put the economy on a more sustainable consumption-driven growth path. This especially applies to the man at the top, President Xi Jinping.

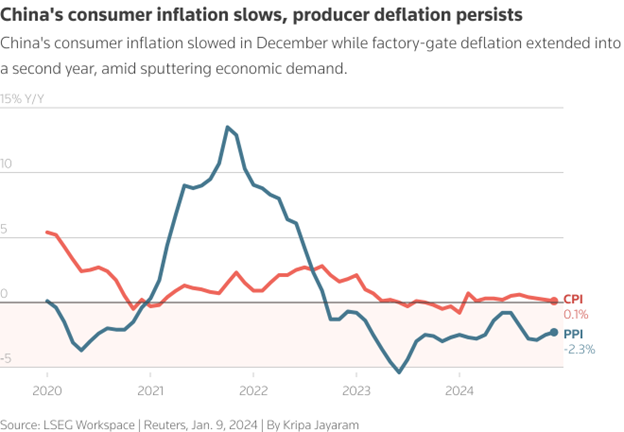

The December data for inflation is now in and once again, the numbers do not bode well for China’s chances of avoiding a prolonged downward price spiral. As the Reuters read out[1] of these numbers notes, the consumer price index (CPI) barely rose, increasing by 0.1% year-on-year. This rise was slightly smaller than the 0.2% gain in November. The full year 2024 CPI increase came to just 0.2%, well below the official target of a 3% rise for the year, marking the 13th year in a row that this has happened. At the factory gate, the producer price index (PPI) fell 2.3% year-on-year in December. That was slightly less than November’s 2.3% drop, but marked the 27 straight month the PPI had declined.

The CPI continued to flatline, while the PPI kept falling, despite Chinese Government economic stimulus efforts during the fall. Commenting on these latest data in Reuters, Zhang Zhiwei, president and chief economist at Pinpoint Asset Management, observes, “The deflationary pressure is persistent,” adding, “The property sector downturn has not ended, which continues to weigh on consumer sentiment.”

Speaking of the housing market crash weighting on consumer sentiment, Barclays estimates[2] that the steep fall in housing prices since the 2021 bursting of the property bubble has erased $18 trillion of Chinese household wealth, eclipsing the hit the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis inflicted on American household wealth. The huge scale of this wealth destruction is one reason why Chinese consumers have been reluctant to open their wallets since the pandemic. There is no prospect for a rebound in housing prices, due to huge supply of vacant unsold flats and villas. As of November 2024, China had 80 million unsold units,[3] or half the total US housing stock.

Official Chinese Government data has always been something to be taken with a large grain of salt and this appears to be the case with the latest figures for GDP growth,[4] which pegs it at 5.2% for 2023, while projecting a 4.8% rise in 2024. However, the highly respected Rhodium Group[5] has argued that these numbers should be much lower, noting that the weakness in investment and local government spending over the past three years do not square with the official GDP growth data. They argue that China’s GDP rose just 1.5% in 2023 and 2.4-2.8% in 2024, well below the growth rates reported by the government. These revisions were echoed by Gao Shanwen,[6] the chief economist for the State Development and Investment Corporation, the largest Chinese state-owned investment company, in a speech delivered at a December 3rd investor conference in Shenzhen. This address, which characterized post-pandemic Chinese society as being “full of vibrant old people, lifeless young people, and despairing middle-aged people,” claimed that official government data has overstated GDP growth by 3% for each of the past three years. The Rhodium Group estimates that China could get 3-4.5% GDP growth in 2025, reaching the high end of that range only if everything goes right. Even that high end forecast is below the 5% GDP growth target[7] set by the Chinese Government for 2025.

Finally, late November saw the yield on 30-year Chinese government bonds[8] fall to 2.21%, down from 4% in late 2020. This is the first time China’s long-term bond yields had fallen below those for Japan. Yields of shorter-term 2- and 10-year Chinese and Japanese bonds have been rapidly converging,[9] and the former may also fall below the latter. The collapse in Chinese bond yields reflects slowing economic growth and lackluster consumer demand, underscoring that the threat of deflation is alive and well in the world’s number two economy. This trend has been paralleled by rising capital flight, with $45.7 billion leaving China in November[10]—incomes from cross-border receipts from portfolio investment amounted to $188.9 billion, while payments came to $234.6 billion, the biggest monthly deficit on record.

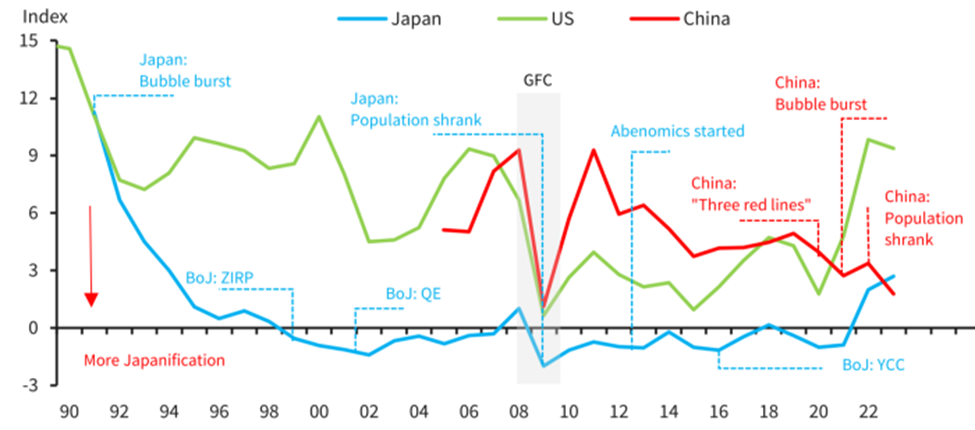

The convergence of Chinese and Japanese bond yields, coupled with the raft of other dismal economic indicators in China, has generated considerable speculation around the possible “Japanification” of the People’s Republic. To be sure, very few people, including myself, would argue China will inevitably duplicate Japan’s long period of sluggish economic growth that began in the 1990s. However, there is now growing agreement that such an outcome is very possible. Just as Japan experienced the popping of equity and real estate bubbles at the outset of its “lost decade,” China has now seen the popping of a huge property bubble, followed by a rapid fall in housing prices, which have dropped by as much as 30% from their 2021 peak.[11] Thus, Barclays economists[12] have applied an index of “Japanification” index devised by a Japanese economist, Takatoshi Ito, to China. This index measures the sum of the inflation rate, nominal policy rate, and GDP gap. In applying it to the Chinese economy, the Barclays team replaced the GDP gap with working age population growth. They did so because the estimation measures of GDP gaps differ across countries, making working age population growth a much better underlying determinant of economic growth. Their amended index showed that China’s economy has recently become more, albeit narrowly, “Japanised” than its Japanese counterpart.

Source: Robin Wiggelsworth, “China is Turning Japanese. At least that’s what the Bond Market is Whispering,” Financial Times, October 17, 2024.

Demography is one key area where China is more “Japanised” than Japan as it possibly enters into a prolonged economic slowdown. Although both countries face severe demographic issues that are related to their economic growth trajectories, China’s demographic problems are of a higher order magnitude than those of Japan.

According to official Chinese Government data,[13] the population of China dropped by 2.08 million people in 2023 after declining by 850,000 people in 2022. It bears noting that these figures almost certainly understate the recent contraction of China’s population.[14] This trend is set to continue, due to declining fertility rates—the fertility rate is the number of children a woman will give birth to over her lifetime—among Chinese women. Those rates had fallen to 1.15 in 2021,[15] well under the replacement rate of 2.1 needed for a country to sustain its population. In contrast, Japan’s population peaked at 135 million in 2010,[16] nearly two decades after the onset of its “lost decade” in the early 1990s. When it comes to having its population actually decline as the economy possibly enters into a long-term growth slowdown, China has a nearly 20-year head start over Japan. Moreover, while fertility rates in Japan are low, they are not nearly as low as they are in China. In 2024, the fertility rates of Japanese women stood at 1.374;[17] this was a slight uptick from the fertility rates that prevailed from 2000-2023. Thus, despite both China and Japan suffer from adverse demography, the situation is markedly worse in the former. By extension, the collateral economic damage on the labor supply and ability of these countries to produce goods as well as consume them will be greater in China than in Japan during the coming years.

China is also now in markedly worse shape when it comes to household debt compared to Japan at the outset of and during its 1990s-early aughts economic slowdown. China’s debt-to-GDP has recently climbed to truly eye-watering levels, rising to 287.8% in 2023,[18] with Goldman Sachs[19] predicting that it will soon cross the 300% threshold. The debt-to-GDP ratio held by households amounted to 63.5% in 2023 (that year, the debt-to-GDP ratio held by non-financial corporations amounted to 168.4%). Barclays economists quoted in an October 17, 2024 Financial Times[20] article therefore conclude, “We think China’s deleveraging journey has only just started, and it is unlikely to be completed before 2030, which implies the structural headwinds to consumption and investment will persist.” By contrast, Japan’s household debt as a percentage of GDP[21] stood at 35% in 1990, at the outset of its “lost decade” and was still under 50% when that prolonged economic slowdown finally wound down by 2010. At the same time, the share of household wealth tied to property among Japan during its long downturn was half that of their China counterparts at the present moment.[22] This enabled the former to better ride out the steep fall in real estate values following 1990 in Japan than is and will be the case for their Chinese counterparts during China’s real estate meltdown.

Japan also does better with respect to government debt at the start of the its “lost decade” compared to China at the present moment. In the early 1990s, Japan’s government debt to GDP ratio stood at between 63-66% before rising rapidly over the next two decades.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED, Economic Data St. Louis Fed) https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/GGGDTAJPA188N#

In China, on the other hand, the International Monetary Fund (IMF)[23] puts the current Chinese government debt to GDP ratio at 84.4%, or markedly higher than that of Japan in the early 1990s. It bears further emphasizing that that figure most likely considerably understates the Sino-Japanese government debt gap. This is because much of the borrowing by Chinese local government entities is “hidden,” i.e. kept off the books on their behalf by opaque investment instruments referred to as “local government finance vehicles.” According to some measures, the cost of servicing this “hidden” local debt[24] exceeds that of servicing the US debt burden before the 2008-2009 financial crisis or that of Europe’s debt burden during the depths of its 2014 sovereign debt crisis.

Moreover, a July 18, 2024 Rhodium Group report,[25] No Easy Fixes: China’s Long-term Consumption Growth, emphasizes that the Chinese Government faces major obstacles to its ability to raise revenue. Thus, China confronts a possible “lost decade” severely constrained in its ability to fiscally respond to a prolonged economic slump. The Rhodium Group notes that China’s taxation system imposes relatively heavy burden on poor households, with the taxes levied on labor and capital being highly regressive across income levels. That, in turn, limits the disposable income of poor Chinse, lowering their consumption growth. Income from capital gains is lightly taxed in China compared to international norms, creating relatively high levels of income inequality and limiting the share personal income taxes in overall tax revenues, while there is no tax on inheritance and gifts. And last but certainly not least, most local Chinese governments do not levy property taxes. This has forced them to rely on revenues from land sales, which have nosedived during China’s property meltdown, falling by 18.3% during the first 6 months of 2024.[26] The contrast with Japan is especially stark in this area: local Japanese governments[27] have long raised revenues from property taxes and benefit from a robust system of revenue sharing with the central authorities in Tokyo. The Rhodium notes that tax reform, particularly implementing a property tax, “will face powerful vested interests and political resistance,” adding that this opposition “is likely to increase with the property market’s downturn.”

Present-day China also lags behind Japan at the outset of its 1990s protracted economic with respect to providing a safety net for economically distressed households. The July 18, 2024 Rhodium Group report notes that according to recent OECD and Chinese Government data, social transfers in kind and social benefits other than social transfers in kind comprised just under 15% of China’s GDP. The figure for Japan was a bit over 25%. The impact of the relatively threadbare Chinese social safety net is especially evident in household spending on health, due to the far greater risk of being hit with high expenditures for medical catastrophes. In China, the proportion of the population where household spending on health exceeds 10% of household budgets amounts to close to 25%. In Japan, on the other hand, which has a robust system of universal health insurance coverage, that figure stood at 2.2% in 2015,[28] well below the OECD average of 2.9%. It is worth noting that in China, scholarly research has shown that the need to set aside funds for catastrophic medical expenses affects both lower- and upper-income households,[29] even after the 2014 National Cooperative Medical Insurance Scheme extended varying levels of health insurance to 95% of the population. Finally, the various Japanese government stimulus packages of the late 1990s[30] attached considerable weight to supporting employment to counteract rising joblessness, while boosting overall social spending.

Even if China’s government leaders had the fiscal resources to expand the social safety net for households in need of assistance, it is not at all clear that they would do that. In the case of provincial and local authorities, the post-mid 1990s fiscal relationship between them and Beijing, whereby the former are starved of revenue, incentivized them to prioritize funding manufacturing and infrastructure projects. Besides generating immediate revenues through land sales and creating avenues for graft and corruption,[31] such projects can boost economic growth over the short-term, even if they fail to generate sustained returns on investments over the long haul. This matters hugely for heads of local and provincial governments, whose prospects for promotion up the state and Communist Party hierarchy depend on their ability to meet economic growth targets.

The opposition to transferring income to households via spending on social services is even more pronounced in the case of China’s top leader, President Xi Jinping. In October of 2021, Xi wrote an essay[32] in the Communist Party journal, Qiúshì (求是) inveighing against “welfarism;” citing the cases of populist Latin American countries, he argued that generous welfare benefits fostered “lazy people who got something for nothing.” This comment, which came in the context of a general address concerning “common prosperity,” was directed against the then rapidly growing “lying flat,” 躺平 (tăng pīng), mindset that was sparked by high levels of youth unemployment, particularly among university graduates. “Lying Flat” adherents eschewed trying to get ahead under these circumstances in favor of just getting by and taking on a minimalist lifestyle. Xi’s call for Chinese youth to buckle down and work harder fell on deaf ears: “Lying Flat” has recently been overtaken by the 摆烂 (bǎi làn), or “let it rot,” movement,[33] in which individuals actively embrace their worsening economic circumstances rather than seeking to change them for the better.

Besides being hostile to strengthening the China’s social safety net, Xi has been unwilling to grasp the seriousness of the deflation threat to its economy. He reluctantly gave a green light[34] to the limited fall government economic stimulus package only after reports streamed into Beijing regarding the liquidity crisis facing financially local governments, with municipalities teetering on the edge of bankruptcy. In a December 23, 2024 article,[35] Wall Street Journal correspondent Wei Lingling, who has done excellent reporting about central Chinese Government decision-making, noted that Xi views American-style consumption as “wasteful.” According to people close to inner power circles, Xi asked, “What’s so bad about deflation? Don’t people like it when things are cheaper?” This cavalier attitude has made the topic of deflation a totally taboo subject in economic policymaking discussions. The refusal to acknowledge bad economic news is further underscored by the recent disciplining of the economist Gao Shenwan. As was noted earlier, Gao has suggested that the Chinese GDP growth rate was actually well below official Government figures. After hearing this, as well as comments Gao made at a Washington, DC conference about the government’s inability to stimulate the economy, Xi is said to have gone totally ballistic,[36] personally banning the economist from speaking in public.

As I said at the outset of this blog post, my personal view is that while China experiencing a Japan style economic “lost decade” is very possible, it is by no means inevitable. With right policies aimed at transferring income to households and boosting their consumption, the country can avoid that fate. Such changes, couple with China’s undeniable strengths in fields like AI, electric vehicles, and other green energy sectors, could put its economy on a stronger and more durable long-term growth path. Alas, the clear unwillingness of Chinese leaders to even admit that Japan-style deflation and attendant balance sheet recession is a threat, let alone begin to seriously address it, does not auger well for their country’s future economic prospects.

[1]. “China’s consumer prices stall in 2024 on feeble demand,” Reuters, January 8, 2025. URL:

https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/chinas-consumer-inflation-slows-dec-2025-01-09/.

[2]. “Economists Urge China to Ramp Up Housing Rescue to Propel Growth,” Bloomberg News, September 22, 2024. URL: https://www.bnnbloomberg.ca/business/international/2024/09/22/economists-urge-china-to-ramp-up-housing-rescue-to-propel-growth/.

[3]. Jason Douglas and Ming Li, “China’s Economy is Burdened by Years of Excess,” Wall Street Journal, January 1, 2025. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/china/china-economy-excess-debt-gdp-46c69585.

[4]. “Growth Rate of real gross domestic product (GDP) in China from 2013 to 2023 with forecasts until 2029,” Statista, no date. URL: https://www.statista.com/statistics/263616/gross-domestic-product-gdp-growth-rate-in-china/.

[5]. Daniel H. Rosen, Logan Wright, Jeremy Smith, Matther Mingey, and Rogan Quinu, “After the Fall: China’s Economy in 2025,” Rhodium Group, December 31, 2025. URL: https://rhg.com/research/after-the-fall-chinas-economy-in-2025/.

[6]. “The Youth are ‘Lifeless:’ Economist’s Speech Goes Viral in China,” Bloomberg, December 3, 2024. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-03/the-youth-are-lifeless-economist-s-speech-goes-viral-in-china.

[7]. “Exclusive: China plans record budget deficit of 4% of GDP in 2025, say sources,” Reuters, December 17, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/china-plans-record-budget-deficit-4-gdp-2025-say-sources-2024-12-17/.

[8]. Arjun Niel Alim and Ian Smith, “China Bond Market Grapples with Japanification,” Financial Times, November 29, 2024. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/d299727e-41a1-480b-a44d-780b290bc3c0.

[9]. Jamie McGeever, “China’s tumbling bond yields intensify ‘Japanification’ risks,” Reuters, January 8, 2025. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/chinas-tumbling-bond-yields-intensify-japanification-risks-mcgeever-2025-01-08/

[10]. “China capital markets outflow hits record high in November after Trump election,” Reuters, December 16, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/china-capital-markets-witness-record-outflows-nov-official-data-shows-2.024-12-17/.

[11]. Paul Hodges, “China’s Housing Market: From Boom to Bust,” Independent Commodity Intelligence Services (ICIS), May 19, 2024. URL: https://www.icis.com/chemicals-and-the-economy/2024/05/chinas-housing-market-moves-from-boom-to-bust/.

[12]. Lukas Gehrig, “Macro-China: Is China having its ‘big bazooka’ moment?” Barclays, November 15, 2024. URL: https://privatebank.barclays.com/insights/2024/november/outlook-2025/is-china-having-its-big-bazooka-moment/#:~:text=Originally%20introduced%20by%20Japanese%20economist,working%20age%20population%20gap%20instead

[13]. Jacob Funk Kirkegaard, “China’s population decline is getting close to irreversible,” Petersen Institute of International Economics, January 18, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/research/piie-charts/2024/chinas-population-decline-getting-close-irreversible.

[14]. Qin Mei, Scott Kennedy and Ilaria Mazzocco, “China is Growing Old Before it Becomes Rich: Does it Matter?” Center for Strategic and International Studies: China Big Data, September 21, 2023. URL: https://bigdatachina.csis.org/china-is-growing-old-before-it-becomes-rich-does-it-matter/#:~:text=China%20does%20not%20have%20the,old%20before%20it%20becomes%20rich.

[15]. Carl Minzer, “China’s Population Decline Continues,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 26, 2024. URL: https://www.cfr.org/blog/chinas-population-decline-continues#:~:text=Statistics%20suggest%20that%20China’s%20total,would%20maintain%20current%20population%20levels.

[16]. Naoyuki Yoshino and Farhad Taghizadeh-Hesary, “Japan’s Lost Decade: Lessons for Other Economies,” Asia Development Bank Institute (ADBI) Working Paper Nr. 52, April 2015. URL: https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/159841/adbi-wp521.pdf.

[17]. “Japan’s Fertility Rates, 1950-2025,” Macrotrends.net, no date. URL: https://www.macrotrends.net/global-metrics/countries/jpn/japan/fertility-rate.

[18]. Xia Ying and Han Wei, “China’s debt-to-GDP ratio climbs record 287.8% in 2023,” Caixin, January 30, 2024. URL: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Caixin/China-s-debt-to-GDP-ratio-climbs-to-record-287.8-in-2023.

[19]. “Will China’s Policy Stimulus be Enough?” Goldman Sachs Global Macro Research, December 11, 2024. URL: https://www.goldmansachs.com/pdfs/insights/goldman-sachs-research/will-chinas-policy-stimulus-be-enough/ChinaTopOfMind.pdf.

[20]. Robin Wiggelsworth, “China is Turning Japanese. At least that’s what the Bond Market is Whispering,” Financial Times, October 17, 2024. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/64019d3e-ac4a-4d94-8f33-b0148cab0d2f

[21]. Shinobu Nakagawa and Yosuke Yasui, “A Note on Japanese household debt: international comparison and implications for financial stability,” Bank of International Settlements Paper Nr. 46, May 25, 2009. URL: https://www.bis.org/publ/bppdf/bispap46.htm.

[22]. Lukas Gehrig, “Macro-China: Is China having its ‘big bazooka’ moment?” Barclays, November 15, 2024. URL: https://privatebank.barclays.com/insights/2024/november/outlook-2025/is-china-having-its-big-bazooka-moment/#:~:text=Originally%20introduced%20by%20Japanese%20economist,working%20age%20population%20gap%20instead.

[23]. “Debt Mapper: Global Debt Database, General Government Debt,” International Monetary Fund, no date. URL: https://www.imf.org/external/datamapper/GG_DEBT_GDP@GDD/CAN/FRA/DEU/ITA/JPN/GBR/USA.

[24]. Jason Douglas and Ming Li, “China’s Economy is Burdened by Years of Excess,” Wall Street Journal, January 1, 2025. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/china/china-economy-excess-debt-gdp-46c69585.

[25]. Logan Wright, Camille Boullenois, Charles Austin Jordan, Endeavour Tian, and Rogan Quinn, “Easy Fixes: China’s Long-term Consumption Growth,” Rhodium Group, July 18, 2024. URL: https://rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/.

[26]. “China’s revenue from government land sales down 18.3% year on year,” Reuters, July 22, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-revenue-government-land-sales-down-183-year-year-2024-07-22/.

[27] “Financial Innovation for Municipal Infrastructure and Public Service Project,” World Bank Group, September 11-15, 2023. URL: https://www.worldbank.org/en/programs/tokyo-development-learning-center/tdd/property_tax_and_land_based_financing_story#:~:text=Reevaluating%20Property%20Taxes%20and%20Land,economic%20impact%20through%20these%20tools.

[28]. Toshiyuki Sasaki, Masahiro Izawa, and Yoshikazu Okada, “Current Trends in Health Insurance Systems: OECD Countries vs. Japan,” National Institute of Health (NIH): National Library of Medicine, March 23, 2015. URL: https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC4628174/#:~:text=The%20share%20of%20out%2Dof,for%20the%2034%20OECD%20countries.

[29]. Ning Ning, Ye Li, Ye Li, Qunhong Wu, Chaojie Liu, Zheng Kang, Xin Xie, Hui Yin, Mingli Jiao, Guoxiang Liu, and Yanhua Hao, “Catastrophic Health Expenditure and Rural Household Impoverishment in China: What Role doe the New Cooperative Health Insurance Scheme Play?” PLOS.One (Public Library of Science One), April 8, 2014. URL: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0093253.

[30]. “Revisiting Japan’s Lost Decade. Fiscal Policy: Did Stimulus Work?” International Monetary Fund: IMF E-Library, May 5, 2009. URL: https://www.elibrary.imf.org/display/book/9781589068407/ch04.xml#:~:text=Fiscal%20Policy:%20Did%20Stimulus%20Work?&text=The%20effectiveness%20of%20fiscal%20policy%20in%20Japan%20during%20the%20lost,as%20some%20mistimed%20consolidation%20efforts.

[31]. Logan Wright, Camille Boullenois, Charles Austin Jordan, Endeavour Tian, and Rogan Quinn, “Easy Fixes: China’s Long-term Consumption Growth,” Rhodium Group, July 18, 2024. URL: https://rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/.

[32]. Jane Ni, “Xi Jinping’s vision for China does not involve workers ‘lying flat,’” Quartz, October 19, 2021. URL: https://qz.com/2075649/lying-flat-is-not-in-xi-jinpings-vision-for-china.

[33]. Vincent Ni, “The rise of ‘bai lan:’ why China’s frustrated youth are ready to ‘let it rot,’” Guardian, May 25, 2022. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/26/the-rise-of-bai-lan-why-chinas-frustrated-youth-are-ready-to-let-it-rot.

[34]. Wei Lingling, “Behind Xi Jinping’s Pivot on Broad China Stimulus: A Bevy of bad news prompted action for the leader—but not a full U-Turn,” Wall Street Journal, October 15, 2024. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/china/behind-xi-jinpings-pivot-on-broad-china-stimulus-08315195.

[35]. Wei Lingling, “Xi Digs in with Top-Down Economic Plan Even as China Drowns in Debt. Xi Jinping is bracing for a showdown, sticking with economic policies aimed at making China the world’s most powerful country,” Wall Street Journal, December 23, 2024. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/china/china-xi-debt-economic-plan-13aaeec1.

[36]. Wei Lingling, “Xi Jingping Muzzles Chinese Economist Who Dares to Doubt GDP Numbers. Gao Shenwan questioned Beijng’s ability to boost its economy as threats loom from a property meltdown, burgeoning debt and other challenges,” Wall Street Journal, January 8, 2025. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/china/xi-jinping-muzzles-chinese-economist-who-dared-to-doubt-gdp-numbers-2a2468ef.