Politics has always been an extremely fraught topic in China. More recently, as the Chinese economy encounters ever greater headwinds, frank discussions about these economic challenges have become increasingly dodgy and subject to stricter controls by government authorities.

In the summer of 2023, numerous local brokerage analysts, researchers at leading universities, and state-run think tanks were instructed by government officials[1] not to comment negatively about a wide array of topics, ranging from fears of capital flight to price deflation. This gag order applied not just to employees of such organizations, but to domestic Chinese media as well. Some topics were declared to simply be off-limits.

More ominously, a leading economist at the prestigious government-run think tank, the Chinese Academy of the Social Sciences (CASS), Zhu Hengpeng, was “disappeared”[2] after last being seen in public in April. This happened after Zhu made disparaging comments about China’s economy and, by extension, Xi Jinping and other top leaders in a private WeChat group. At the same time, authorities initiated a shakeup at CASS, removing its director and general secretary from their posts. Zhu is no longer listed on the CASS website, while websites related to his research work at Tsinghua University have been taken offline.

This backdrop makes the blunt commentary on China’s economy issued by Gao Shanwen, the chief economist for the State Development and Investment Corporation, the largest Chinese state-owned investment company, at the start of December all the more shocking. Gao, who has previously advised top Chinese regulators and officials, made his remarks at a December 3rd investor conference in Shenzhen.

According to the Bloomberg review[3] of Gao’s address, he characterized post-pandemic Chinese society as being “full of vibrant old people, lifeless young people, and despairing middle-aged people.” This harsh verdict was based on post-pandemic consumer behavior among different age groups, with Gao noting, “The younger a province’s population is, the slower its consumption growth has been.” He added that this correlation between regional consumption levels and demographic profiles did not exist prior to Covid.

Gao observed that this pattern regarding the age profile of provinces and their consumption levels did not exist prior to the Covid Pandemic. He argues the higher consumption levels among the elderly during and after Covid stemmed from greater stability in their incomes. Retirees continued receiving their pension payouts through the Covid lockdown related economic disruptions. These individuals, it could be further added, had fully paid for the flats they had purchased when the government began allowing people to buy and sell real estate during the 1990s and were not burdened by mortgage payments.

However, as I argued in an earlier June 15th blog post, the consumption patterns of these seniors differ markedly from those of young and middle-aged adults. In particular, demand for the consumer durable goods like cars, electronic goods, and home appliances China continues to churn out is much lower among the elderly compared to people in their 20s, 30s, 40s, and 50s.

In contrast to elderly pensioners, young people were especially hard hit by the economic disruption caused by the Covid lockdown, as well as the recent Chinese Government crackdown on the high-tech and education/training sectors. The official unemployment rate for those aged 16-24 stood at 17.6% in September.[4] Facing increasingly dim economic prospects, growing numbers of Chinese youth, including university graduates, have embraced the “lying flat,” 躺平[5] (tăng pīng), and more recent 摆烂 (bǎi làn), or “let it rot,[6]” movements. Adherents of these outlooks embrace a minimalist lifestyle over fulfilling traditional consumption norms and expectations.

Post Covid economic anxieties are also present among Chinese in their 30s and 40s. This demographic is also facing a tougher labor market,[7] with those affected by the growing number of layoffs across different industries having to deal with the widespread reluctance among employers to hire people who are older than 35 years of age.

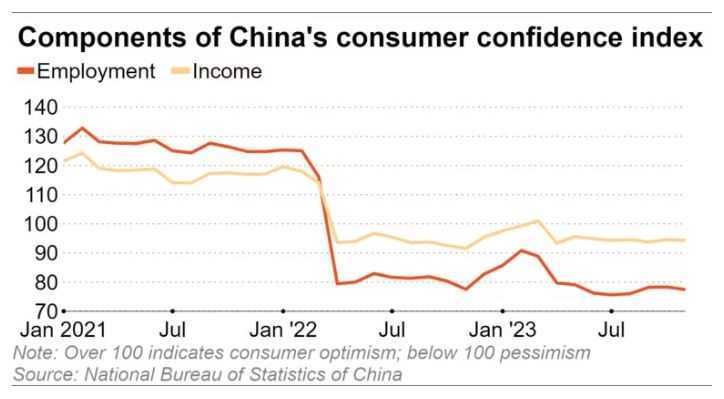

Confronted with growing insecurity around their employment prospects and income, it is hardly surprising that Chinese consumers are reining in their purchases. The link between employment and income on the one hand and consumer confidence on the other is illustrated in the graph below, which appeared in a January 18, 2024 Nikkei Asia[8] story on growing joblessness among middle-aged Chinese.

In his Shenzhen address Gao speculated that the number of Chinese living in urban areas unable to find formal employment over the past three years may have totaled 47 million, despite the official unemployment rate[9] remaining stable at around 5%. According to Bloomberg calculations based on official Chinese Government statistics, that is equivalent to 10% of China’s urban labor force in 2023, or double the official urban unemployment rate. In making this claim, Gao cited his analysis of pre-pandemic trends in urban employment data.

Besides pouring cold water over Chinese Government employment data, Gao called into question the official figures for the growth of China’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP). In a further startling claim, he argues official estimates of the Chinese GDP may have been over-counted by 10 percentage points over the past three years. Gao bases this claim on his analysis of the gap between Chinese economic growth data and expansion in areas like consumption, investment, and the labor force.

Gao’s bearish commentary on the Chinese economy clearly struck a chord, immediately going viral on social media before being quickly scrubbed by government censors.[10] This move came shortly before the high-profile and politically sensitive December 11-12th meeting of the Communist Party’s Central Economic Work Conference charged with charting economic policy for the upcoming year. This happened despite Gao arguing in his speech that China’s current economic problems were cyclical, not structural, in nature. Whether Gao really believes this to be the case or said this due to his position at the largest Chinese state-owned investment company and to avoid political difficulties is hard to say. In any case, it did not prevent his comments from being quickly erased from Chinese social media.

Gao is not the only well-known Chinese economist to recently run afoul of Beijing authorities for being bearish on the Chinese economy. Back in September, Fu Peng, the chief economist at Northeast securities, was also blocked on social media[11] after his comments on weak consumption in China went viral.

In an address delivered at the 2024 Phoenix Financial Forum for the Greater Bay Area, Fu sounded pessimistic about raising consumption levels among ordinary Chinese.[12] He argued that falling property prices were the main culprit behind current anemic consumer demand in the Chinese economy. Fu noted that the property crash had left middle-class homeowners with negative equity, making them reluctant to loosen their wallets. In making this claim, he further argued that increasing middle-class consumption over the past decade was driven less by rising incomes as opposed to the rapid appreciation in property values over this period fueled by China’s real estate bubble. Fu concluded that the difficulty in reviving the post-bubble real estate sector, coupled with China’s worsening demographic crisis, was “very dangerous signal” for rebalancing the economy toward greater consumption. That, in turn, raised the specter of China experiencing its own 1990s Japan-style “lost decade.”

As Stephen Roach, former chairman of Morgan Stanley Asia and now Yale University faculty member notes, “The Japan comparison hits a raw nerve in China.” Commenting in Project Syndicate[13] on a post-2024 US Presidential election tour of Asia, which included several stops in the People’s Republic, Roach was struck by the sense of denialism he encountered on this subject. One case in point was a senior Chinese regulator who conceded that the steep drop in property and equity markets, mounting debt burdens, early signs of deflation, and weak productivity and an aging workforce all posed major economic headwinds. However, when Roach reminded this fellow that all of these things were present in the runup to Japan’s 1990s “balance sheet” recession, he went into instant and vehement denial about that scenario.

To be sure, with the right policies, China can still avoid this fate. But doing that will first and foremost involve raising the share of the GDP taken by household consumption, which currently stands at just 39%, well below the OECD average of 54%.[14] Raising that figure will involve redistributing resources away from investment, the government, and actors tied to the government, like state-owned enterprises, to households. Unfortunately, this is a step which the regime seems unwilling to take. mainly for political reasons. High-ranking Government officials are now even reluctant to concede top leader Premier Wen Jiaobao’s famously prescient diagnosis, made nearly two decades ago in 2007, that China’s economy was “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable.”

The first step in solving a problem is acknowledging its existence and scope and then to properly diagnosing it. When it comes to the crisis currently facing China’s economy, the recent stifling of blunt and honest discussion of this problem underscores that top Chinese leaders have not fully grasped the nature of this problem. Until they do, putting the country on a sustainable growth path will remain a very heavy lift indeed.

[1]. Sun Yu, “Chinese Economists told not be negative as rebound falters. Authorities struggling to restore confidence in post-Covid recovery want analysts to avoid mention of deflation,” Financial Times, August 5, 2023. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/b2e0ad77-3521-4da9-8120-1f0c1fdd98f8.

[2]. Chun Han Wong, “Top Economist in China Vanishes After Private WeCat Comments,” Wall Street Journal, September 24. 2024. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/china/top-economist-in-china-vanishes-after-private-wechat-comments-50dac0b1.

[3]. “The Youth are ‘Lifeless:’ Economist’s Speech Goes Viral in China,” Bloomberg, December 3, 2024. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-12-03/the-youth-are-lifeless-economist-s-speech-goes-viral-in-china

[4]. “China’s youth unemployment rate falls after climbing for two straight months,” Reuters, October 21, 2014. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-sept-youth-jobless-rate-176-compared-with-188-august-2024-10-22/.

[5]. Ivana Davidovic, “’Lying flat:’ Why some Chinese are putting work second,” BBC News, February 15, 2022. URL: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-60353916.

[6]. Vincent Ni, “The rise of ‘bai lan:’ why China’s frustrated youth are ready to ‘let it rot,’” Guardian, May 25, 2022. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2022/may/26/the-rise-of-bai-lan-why-chinas-frustrated-youth-are-ready-to-let-it-rot.

[7]. Ior Kawate, “China over-35s hit age barriers in tough labor market. Midcareer workers snubbed or laid off by struggling companies seeking cheaper hires,” Nikkei Asia, January 18, 2024. URL: https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/China-s-over-35s-hit-age-barriers-in-tough-labor-market.

[8]. Ior Kawate, “China over-35s hit age barriers in tough labor market. Midcareer workers snubbed or laid off by struggling companies seeking cheaper hires,” Nikkei Asia, January 18, 2024. URL: https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/China-s-over-35s-hit-age-barriers-in-tough-labor-market.

[9]. “Unemployment rate in urban China from 2017 to 2023 with forecasts until 2029,” Statista, no date. URL: https://www.statista.com/statistics/270320/unemployment-rate-in-china/.

[10]. “Two critical online views on China’s economy vanish ahead of policy meeting,” Reuters, December 6, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/two-critical-online-views-chinas-economy-vanish-ahead-policy-meeting-2024-12-06/#:~:text=Two%20critical%20online%20views%20on%20China’s%20economy%20vanish%20ahead%20of%20policy%20meeting,-By%20Reuters&text=BEIJING%2C%20Dec%206%20(Reuters),the%20country’s%20tightly%20controlled%20internet.

[11]. “Two critical online views on China’s economy vanish ahead of policy meeting,” Reuters, December 6, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/two-critical-online-views-chinas-economy-vanish-ahead-policy-meeting-2024-12-06/#:~:text=Two%20critical%20online%20views%20on%20China’s%20economy%20vanish%20ahead%20of%20policy%20meeting,-By%20Reuters&text=BEIJING%2C%20Dec%206%20(Reuters),the%20country’s%20tightly%20controlled%20internet.

[12]. Mandy Zuo, “China’s ‘conscientious economist’ goes viral by speaking the truth. Straightforward and critical remarks by Northeast Securities’ chief economist Fu Peng on China’s economy have gone viral on Chinese media,” South China Morning Post, September 13, 2024. URL: https://www.scmp.com/economy/china-economy/article/3278446/chinas-conscientious-economist-goes-viral-speaking-truth.

[13]. Stephen Roach, “Asia in Denial,” Project Syndicate, November 26, 2024. URL: https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/asia-denial-problems-facing-chinese-economy-trump-tariffs-by-stephen-s-roach-2024-11.

[14]. Logan Wright, Camille Boulenois, Charles Austin Jordan, Endeavor Tian, and Rogan Quinn, “No Quick Fixes: China’s Long-Term Consumption Growth,” Rhodium Group, July 18, 2024. URL: https://rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/.