The Chinese economy continues to disappoint when it comes to deflation, consumer spending, economic growth, and recently even exports. The latest numbers in these areas are almost uniformly dismal and have prompted Beijing to finally take major action to revitalize China’s anemic economy. The question is whether or not these measures will be effective.

First the most recent data, starting with the trend in prices. According to an October 13th Reuters article,[1] the consumer price index (CPI) increased just 0.4% from a year earlier in September, compared to a 0.6% hike in August. The September CPI rise was the lowest in three months and fell short of the expected 0.6% mark predicted in a Reuters poll of economists. The producer price index (PPI), which gauges the cost of goods at the factory gate, fell by 2.8% in September, the biggest drop in six months and well below the 1.8% decline in August. Chief Economist and President at Pinpoint Asset Management Zhiwei Zhang declared that “China faces persistent deflationary pressure, due to weak domestic demand.”

The ongoing weakness of consumer spending in China is reflected not only in the disappointing data on prices. It is further underscored by weak spending during the latest week-long National Day Holiday. Analysis done by Goldman Sachs[2] indicates that for this holiday period, spending per domestic trip was 2% below that of pre-pandemic levels.

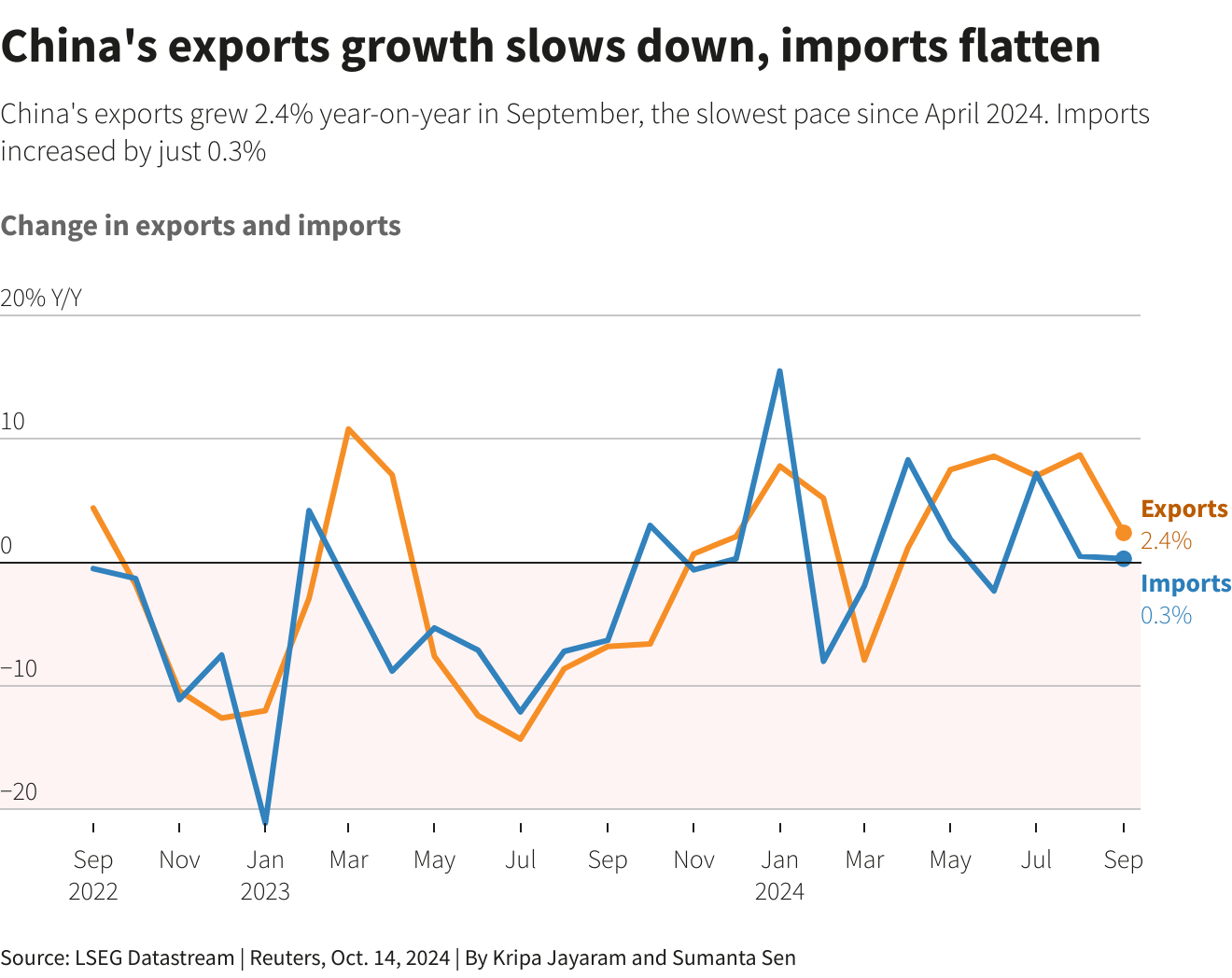

Foreign trade, which had previously been the one bright spot in China’s economic performance, also showed signs of weakening in September.[3] Chinese exports grew that month by just 2.4% on a year-on-year basis, the slowest rise since April, and missing the 6% increase forecasted in a Reuters poll of economists. Imports barely increased, going up 0.3%, which is another indication of weak consumption in China.

blog

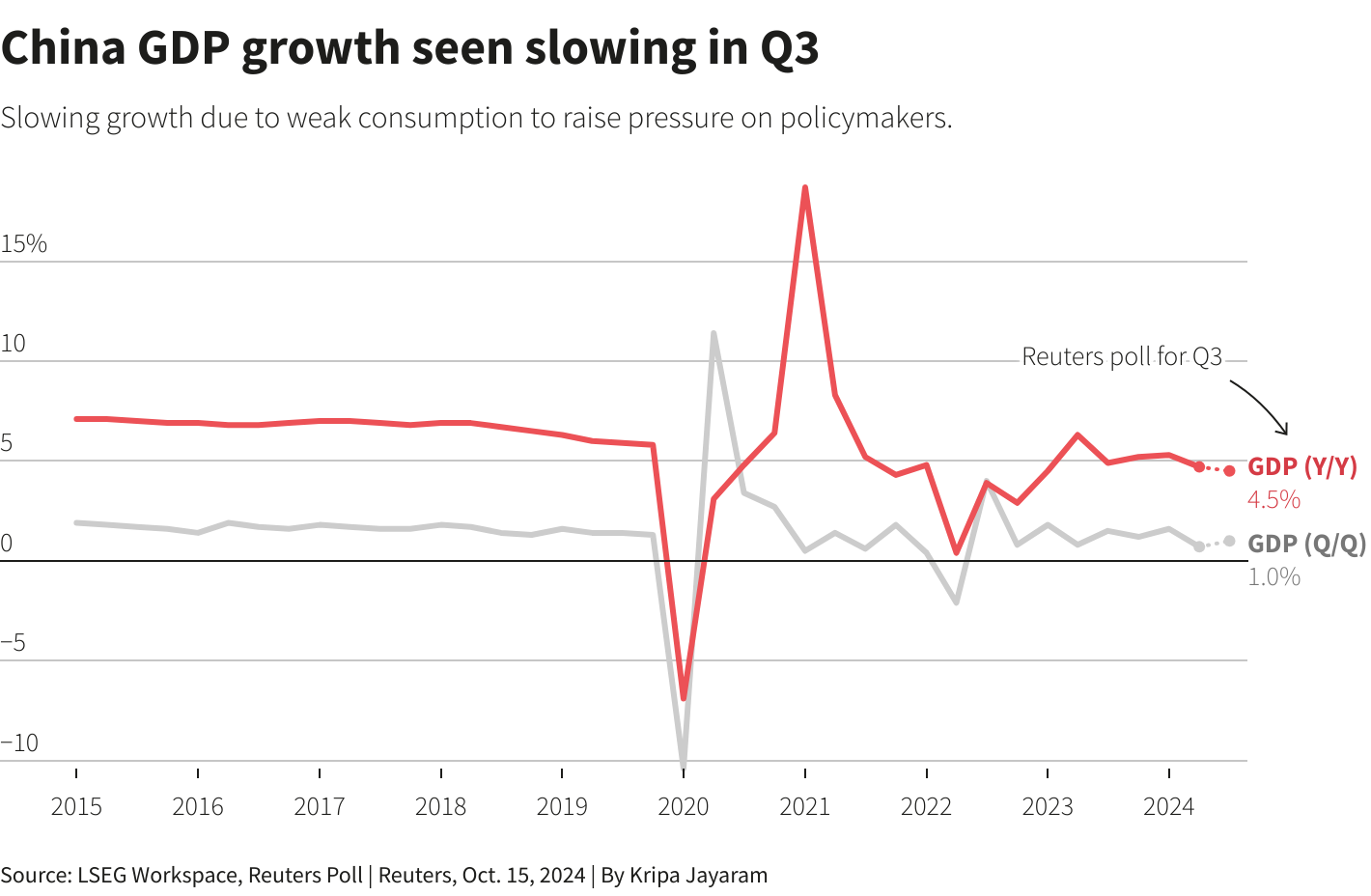

The sluggishness in prices, consumer spending, and trade are reflected in the disappointing figure for third quarter Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth race. Official Chinese Government data has pegged the third quarter GDP growth rate at 4.6%.[4] That figure is in line with a Reuters poll of economists,[5] which predicted a 4.5% increase in China’s GDP over this period from a year earlier. These numbers are lower than the 4.7% GDP growth rate of the second quarter of 2024 and the weakest quarterly GDP increase since the first quarter of 2023. In its latest forecast of economic growth across the world, the International Monetary Fund now predicts[6] that the Chinese economy will expand by 4.8% in 2024, or below the 5% growth target set by the government.

Dr. Johnson famously quipped that the thought of being hanged in a fortnight concentrates the mind wonderfully. To tweak the good doctor’s aphorism, it seems like the latest round of bad economic numbers has finally concentrated the minds of Chinese leaders. After behaving for over a year like a deer stuck in the headlights as China’s economy faltered in the face of increasingly severe headwinds, Beijing is taking action to address its worsening economic crisis.

In late September, China’s central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), announced an ambitious multi-pronged monetary stimulus package[7] aimed at bolstering the anemic housing market and stimulating the economy. The PBOC is cutting bank reserve requirement ratios by half a percentage point, while slashing the main policy interest rate by 0.2%. It is also lowering mortgage interest rates for existing home loans by around half a percentage point and reducing the minimum down payment requirement for buying a second home from 25 to 15%. In a final measure addressing the real estate crisis, funding support is being increased from 60 to 100% for banks providing loans to local state-owned enterprises to purchase excess housing inventory for conversion into affordable flats. The PBOC has also sought to support the stock market, whose value had plunged by 40% since 2021,[8] by providing funding for listed firms to buy back their own shares and non-bank financial entities and institutional investors to purchase equities.

Fiscal policy was conspicuously absent in the late September Chinese Government economic stimulus plan. Wei Lingling, who has done consistently excellent coverage of economic policymaking in Beijing for the Wall Street Journal, reported[9] that President Xi had been reluctant to give the green light to fiscal stimulus. He only changed his mind, Wei notes, after reports streamed in regarding a liquidity crisis confronting China’s financially strapped local governments. In particular, municipalities were teetering on the edge of bankruptcy and lacked the ability to pay civil servants and fund basic services.

As this policymaking drama played out, the October price data[10] underscored the ongoing threat of deflation for China’s economy. The Chinese consumer price index, a key indicator of inflation, rose by only 0.3% year-on-year, slowing from the 0.4% rise in September. Even more worrisome, the PPI fell by 2.9%, marking the 25th monthly decline and exceeding the 2.8% drop in September. The October trade data[11] was also discouraging. While exports rose by 12.7% year on year, their highest jump since increasing by 14.8% in March of 2023, imports underwent an unexpectedly large drop of 2.3%. The fall in imports reflects ongoing weak domestic consumption. At the same time, the spike in exports may be a blip on screen, driven by factors like improved weather conditions, price discounts to capture foreign market share, and the usual peak season leading up to Christmas. Commenting on the October price data, Zhang Zhiwei12] repeated that “Deflationary pressure is clearly persistent in China.”

Given the main motivating factor behind Xi’s fiscal pivot, it comes as no surprise that the latest Chinese Government stimulus package is focused on shoring local government finances. The main legislative body in the Chinese Government, the National People’s Congress, is approving measures allowing local governments to allocate 10 trillion RMB ($1.4 trillion)[13] towards reducing their off-balance sheets, aka “hidden,” debt. This will involve having such entities issue special refinancing bonds to the off-balance sheet debt they racked up through massive borrowing via so-called “Local Government Finance Vehicles” (LGFVs). The “off balance” debt will be swapped in favor lower interest government bonds,[14] thereby saving local governments money on debt interest payments. Chinese economic policymakers estimate that the money saved on interest payments from this swap will amount 600 billion RMB over the next 5 years.[15] These savings would enable cities to avoid cutting the salaries of or even laying off civil servants, give local government contractors money for delayed payments, and the like. Beijing is also pushing local governments to boost spending[16] by issuing all of the special bonds they can issue and putting the funds into productive investments, especially in infrastructure.

Sparing local governments from the need to make pay cuts or lay off their employees will certainly have the mild stimulative effect of putting more money into local economies and boost consumption in them. The same can be for enabling local authorities to pay vendors and contractors for services they have rendered. It may also limit or even end the wave local government shakedowns of successful private companies,[17] which has been driven by the need of cities to supplement their empty coffers. A government-run research body recently published a memo suggesting that nearly 10,000 companies in the high-tech hub Shenzhen and elsewhere in Guangdong province have been caught up in fraudulent regulatory actions. Much of this questionable law enforcement activity has been “cross-jurisdictional” in nature, namely initiated by authorities in heavily indebted poor inland provinces.

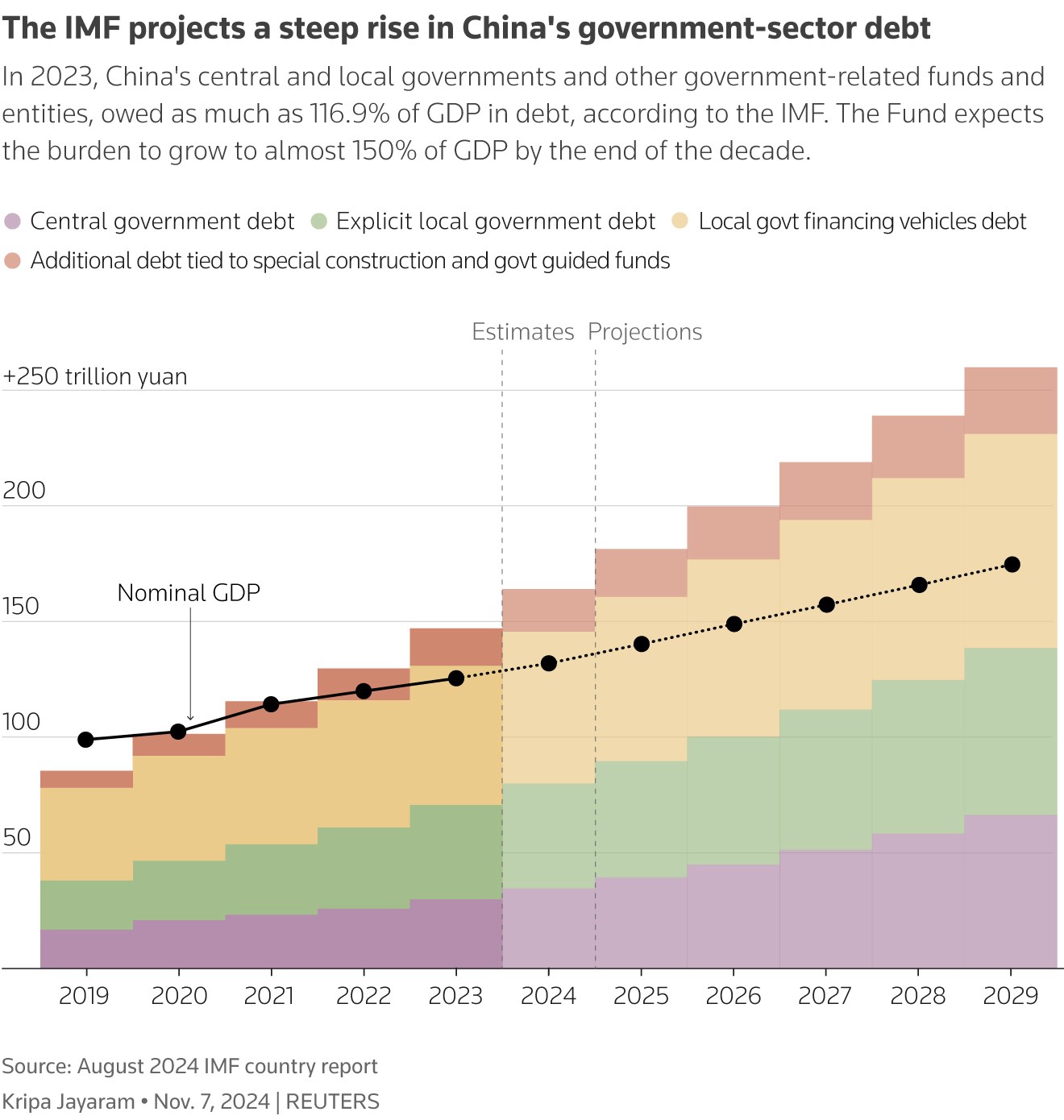

However, freeing up 600 billion RMB for additional local government spending really does not amount to much. With the Chinese 2023 GDP amounting to $17.8 trillion (according to World Bank data),[18] or 128 trillion RMB at the current dollar-RMB exchange rate, the fiscal stimulus stemming Beijing’s debt relief scheme for local governments is very much small beer. At the same time, it seems that Chinese policymakers are seriously understating the size of the local government “hidden debt.” The Finance Ministry estimates that this debt amounted to 14.3 trillion RMB at the end of 2023[19] and plan to trim that to 2.3 trillion by 2028. These figures are yet another example of what Tsinghua University economist Zhu Ning, in his important book, China’s Guaranteed Bubble, calls the “voodoo data” routinely issued by China’s Government. The International Monetary Fund (IMF), by contrast, puts the amount of Chinese local government LGVF “hidden debt” in 2023 at 60 trillion RMB, or nearly half (47.6%), of China’s GDP. Moreover, the IMF forecasts sharply rising levels of local government debt into the foreseeable future.

The Central Government’s other main recently announced fiscal stimulus, the effort to get local authorities to issues more bonds to support investment projects, is also unlike to do much to boost economic activity. As Tianlei Huang of the Peterson Institute of International Economics observes,[20] this move is aimed at reversing the recent course of local government fiscal policy, which has largely been contractionary. Unfortunately, Huang further notes that even if localities issued more bonds, they will face problems spending that money, due to the lack of eligible projects. Starting with the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, China went on a massive infrastructure building binge, with these projects beginning to show diminishing rates of return in 2017.[21] China’s demographic crisis and projected sharp fall in its population will further diminish the future need for additional public infrastructure investment.

The Central Government’s other main recently announced fiscal stimulus, the effort to get local authorities to issues more bonds to support investment projects, is also unlike to do much to boost economic activity. As Tianlei Huang of the Peterson Institute of International Economics observes,[20] this move is aimed at reversing the recent course of local government fiscal policy, which has largely been contractionary. Unfortunately, Huang further notes that even if localities issued more bonds, they will face problems spending that money, due to the lack of eligible projects. Starting with the 2008-2009 global financial crisis, China went on a massive infrastructure building binge, with these projects beginning to show diminishing rates of return in 2017.[21] China’s demographic crisis and projected sharp fall in its population will further diminish the future need for additional public infrastructure investment.

As noted above, prior to the more recently announced fiscal stimulus measures, the PBOC moved to boost the property sector. Besides aiding distressed real estate firms, homeowners, and home buyers, the latter efforts are aimed at easing local government fiscal strains. The sharp downturn in the Chinese real estate has hammered municipal finances across China, which are heavily reliant on income from land sales.

The recent raft of PBOC housing stimulus measures does seem to have given the ailing real estate industry a shot in the arm. Chinese residential property sales rose in October,[22] the first year-on-year increase for 2024. But analysts remain cautious about the long-term prospects of China’s housing market,[23] pointing to the large supply of housing relative to demand, as well as the huge number of pre-sold but unfinished apartments; Nomura Securities estimated that number of such flats amounted to 20 million late last year.

In an earlier blog entry posted in July, I discussed in detail China’s massive oversupply of housing, noting how its adverse demography will depress demand for apartments over the long-term. This problem, I observed, is especially acute in so-called “Tier 3” cities, which consist of poorer provincial capitals and metropolises with large populations but limited political and economic significance. These cities are especially overbuilt. Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff and Yang Yuanchen[24] estimated that the aggregate total housing stock in tier 1-3 Chinese cities rose from 39 billion to 56 billion square meters between 2010-2021. They note that tier 3 cities accounted for 78% of the growth in the housing stock over that decade, despite being home to 66% of Chinese urban residents. Rogoff and Yang estimate that between now and 2035, real estate construction in such places will have to shrink by roughly 30%. Housing prices in these places can therefore be expected to continue falling for some time to come, even in the face of determined central government efforts to prop up the real estate market.

This admittedly grim prognosis bears on the PBOC scheme mentioned earlier to increase funding to local state-owned enterprises to purchases excess housing inventory for conversion into affordable flats. Given the likely downward trend in real estate in 3rd Tier Cities, these firms may well be reluctant to immediately purchase such units, preferring to wait instead for their price to fall further so as to avoid being stuck with a depreciating asset.

In another related move aimed at shoring up property markets, local governments are being allowed to issue to additional special bonds to buy unused land plots and excess housing stock back from real estate firms. Tianlei Huang[25] argues that this bailout for distressed developers could worsen the fiscal problems of local authorities. He notes that the self-financing requirements for such local special bonds “means that any land plots or housing projects that local governments purchase with the bond proceeds will have to generate enough return to cover the interest cost of bond issuance.” If that fails to happen—this is all too likely in the context of the depressed property markets in 3rd Tier cities—the scheme will simply exacerbate crushing local government debt burdens.

The recent two rounds of Chinese Government economic stimulus efforts, then, constitute, at best, a limited first step in reviving China’s economy. They will provide some financial relief for fiscally distressed local authorities and give the real estate market a modest boost, especially in 2nd and 1st Tier Chinese cities, where the oversupply of housing relative to demand is less acute. China may even be able to meet its 5% GDP growth target, in which case the government may declare victory and not undertake further and broader stimulus efforts (more on that shortly). However, Beijing has yet to fully grasp the massive amount of “hidden debt” on local government balance sheets, while much of the country will continue to grapple with large inventories of unsold housing and falling real estate prices and values. The latter problem is going to be further exacerbated by adverse demographic trends, particularly the shrinking cohort of younger and middle-aged homebuyers in China.

Numerous economists both in and outside of China have strongly called for the government to take major steps toward boosting household incomes and consumption. While Beijing does need to bolster local government finances, it should be also be doing all it can to enable consumers to buy more goods. One obvious channel for achieving this aim is strengthening China’s patchy social safety net and increase spending on public health and education, especially for those living in poorer inland lower tier metropolises, the countryside, and rural migrant workers. A July 18, 2024 Rhodium Group report[26] notes that two decades after the 2004 Central Economic Work Conference, when China’s leadership made boosting consumption a stated priority, Chinese household consumption only amounts to 39% of GDP, well below the OECD average of 54%. The obverse of this are high rates of savings, with China having an unusually high gross savings rate[27] compared to both highly developed and other emerging economies. In 2023, the gross savings rate for China stood at 44.3% of GDP, well above the 25.8% average for the EU and India’s 30.2%. Chinese households must set aside large sums of money for education, health care, unexpected financial difficulties, and retirement, leaving of them with limited funds to spend on consumer goods and services. With China’s GDP deflator, which is an important gauge of overall inflation in the economy, coming in at negative now for six consecutive quarters,[28] steps aimed at boosting household consumption are urgently needed to combat deflation.

Unfortunately, this course of action does not appear to be high President Xi’s economic to do list. That much is made clear in the detailed account of the decision making behind the October stimulus provided by Wall Street Journal reporter Wei Lingling reviewed earlier. Her reporting indicates that Xi regarded this move as only a partial U-Turn and limited detour from his ongoing emphasis on having the state drive China’s transformation into an industrial and technological powerhouse. Thus, besides further steps to reduce the large inventory of unsold homes and recapitalizing big state banks, Beijing plans to expand subsidy schemes[29] for factories to upgrade equipment and boost production (consumers may get funds for replacing old appliances and other goods). Xi is clearly doubling down on the old economic growth playbook of boosting investment, albeit not in real estate or infrastructure, but expanding industrial output, especially in advanced sectors, and then exporting that output. However, this hyper mercantilism is provoking backlash not just from the incoming Trump Administration, but the EU[30] and even among China’s BRICs partners[31] as well. If Chinese household consumption levels remain low and China is unable to keep running large current account surpluses, increasing manufacturing output will only boost the supply goods relative demand on the domestic market, thereby fueling more deflation.

To be sure, if economic conditions worsen, Xi may change course. However, methinks that is highly unlikely. Breaking with the existing investment and export driven growth model involves fundamentally rebalancing China’s economy toward consumption and in favor of ordinary households. Doing that would necessarily shift resources away from the state, the Chinese Communist Party, and actors tied to them, thereby diminishing their power. Xi clearly does not want such a thing to happen. If that is the case, the latest government stimulus efforts will be seen as a small speed bump on China’s road to a Japan-style deflationary “lost decade.”

References for Blog Links:

[1]. Gao Liangping and Ryan Woo, “China’s deflationary pressures build in September, Consumer inflation cools,” Reuters, October 13, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/chinas-consumer-inflation-cools-sept-ppi-deflation-deepens-2024-10-13/.

[2]. Evelyn Cheng, “China’s Golden Week Holiday Signals Persistent Consumer Caution,” CNBC, October 9, 2024. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/10/09/chinas-golden-week-holiday-signals-persistent-consumer-caution.html.

[3]. Joe Cash, “China’s Exports Miss Forecasts as Lone Bright Spot Fades,” Reuters, October 14, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/china-sept-export-growth-hits-5-month-low-global-demand-cools-2024-10-14/.

[4]. Joe Leahy, Thomas Hale, and Willam Sandlund, “China’s Economy Grows 4.6% in third quarter. Lowest Figure in year and a half comes as Beijing steps up Stimulus Efforts,” Financial Times, October 15, 2024. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/679f650d-119a-42f8-a1b8-e86df887c375.

[5]. Kevin Yao, “China’s Economy set to Grow 4.8% in 2024, Missing Target: Reuters Poll,” Reuters, October 15, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-economy-set-grow-48-2024-missing-target-2024-10-15/.

[6]. Stella Yifan, “IMF sees global inflation declining, downgrades China growth to 4.8%. U.S. Economy is Expected to Expand by 2.8% as wage hikes lift consumption,” Nikkei Asia, October 22, 2024. URL: https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/IMF-sees-global-inflation-declining-downgrades-China-growth-to-4.8.

[7]. Huang Tianlei, “China’s Stimulus Measures to Boost Troubled Economy may Fall Short,” Peterson Institute of International Economics, October 1, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/chinas-stimulus-measures-boost-troubled-economy-may-fall-short.

[8]. Amy Hawkins, “Chinese stocks suffer worst fall in 27 years over growth concerns,” Guardian, October 9, 2024. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/oct/09/chinese-stocks-suffer-worst-fall-in-27-years-over-growth-concerns.

[9]. Wei Lingling, “Behind Xi Jinping’s Pivot on Broad China Stimulus: A Bevy of bad news prompted action for the leader—but not a full U-Turn,” Wall Street Journal, October 15, 2024. URL: https://www.wsj.com/world/china/behind-xi-jinpings-pivot-on-broad-china-stimulus-08315195.

[10]. Andrew Mullen, “’Deflationary pressure remains’ for China: 4 Takeaways from October’s Inflation Data,” South China Morning Post, November 11, 2024. URL: https://www.scmp.com/economy/economic-indicators/article/3285877/chinas-inflation-edges-october-pressure-remains-despite-monetary-easing?module=perpetual_scroll_1_RM&pgtype=article.

[11]. Anniek Bao, “China October exports record highest jump in 19 months, imports decline more than expected,” CNBC, November 7, 2024. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/11/07/china-october-exports-sharply-beat-estimates-imports-decline-more-than-expected.html#:~:text=Exports%20rose%20by%2012.7%25%20year,in%20October%2C%20customs%20data%20showed.

[12]. Andrew Mullen, “’Deflationary pressure remains’ for China: 4 Takeaways from October’s Inflation Data,” South China Morning Post, November 11, 2024. URL: https://www.scmp.com/economy/economic-indicators/article/3285877/chinas-inflation-edges-october-pressure-remains-despite-monetary-easing?module=perpetual_scroll_1_RM&pgtype=article.

[13]. Samuel Shen and Tom Westbrook, “China’s latest stimulus falls short of expectations,” Reuters, November 8, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/chinas-latest-stimulus-falls-short-expectations-2024-11-08/.

[14]. Tianlei Huang, “Will China’s Stimulus be enough to get its economy out of deflation?” Peterson Institute of International Economics, November 1, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/will-chinas-stimulus-be-enough-get-its-economy-out-deflation.

[15]. “What you need to know about China’s $1.4 trillion debt package,” Reuters, November 10, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/what-you-need-know-about-chinas-14-trillion-debt-package-2024-11-10/.

[16]. Tianlei Huang, “Will China’s Stimulus be enough to get its economy out of deflation?” Peterson Institute of International Economics, November 1, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/will-chinas-stimulus-be-enough-get-its-economy-out-deflation.

[17]. “China’s ‘Broke’ Local Governments Turn to Extortion: Human Rights Watch,” Asia Financial, November 11, 2024. URL: https://www.asiafinancial.com/chinas-broke-local-governments-turning-to-extortion-hrw.

[18]. “China GDP,” Trading Economics, no date. URL: https://tradingeconomics.com/china/gdp.

[19]. “What you need to know about China’s $1.4 trillion debt package,” Reuters, November 10, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/what-you-need-know-about-chinas-14-trillion-debt-package-2024-11-10/.

[20]. Tianlei Huang, “Will China’s Stimulus be enough to get its economy out of deflation?” Peterson Institute of International Economics, November 1, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/will-chinas-stimulus-be-enough-get-its-economy-out-deflation.

[21]. Daniel Rohr, “China’s Infrastructure Projects Suffer Diminishing Returns. Since 2008 returns on infrastructure projects in China have faltered due to oversupply and stalled reform,” Morning Star, October 2017. URL: https://www.morningstar.co.uk/uk/news/161644/chinas-infrastructure-projects-suffer-diminishing-returns.aspx.

[22]. “Chinese Home Sales see first monthly rise in 2024 on Stimulus,” Bloomberg, October 31, 2024. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-10-31/china-home-sales-slump-eases-as-stimulus-boosts-buyer-morale.

[23]. Evelyn Cheng and Anniek Bao, “China’s property market is expected to stabilize in 2025—but stay subdued for years,” CNBC, October 29, 2024. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/10/30/chinas-property-market-is-expected-to-stabilize-in-2025-.html.

[24]. Kenneth Rogoff and Yang Yuanchen, “A Tale of Tier 3 Cities,” IMF Working Paper WP/22/196, September 2022. URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/09/29/A-Tale-of-Tier-3-Cities-524064.

[25]. Tianlei Huang, “Will China’s Stimulus be enough to get its economy out of deflation?” Peterson Institute of International Economics, November 1, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/will-chinas-stimulus-be-enough-get-its-economy-out-deflation.

[26]. Logan Wright, Camille Boulenois, Charles Austin Jordan, Endeavor Tian, and Rogan Quinn, “No Quick Fixes: China’s Long-Term Consumption Growth,” Rhodium Group, July 18, 2024. URL: https://rhg.com/research/no-quick-fixes-chinas-long-term-consumption-growth/.

[27]. “Gross Savings Rate by Country Comparison,” CEIC Data, no date. URL: https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/china/gross-savings-rate.

[28]. Tianlei Huang, “Will China’s Stimulus be enough to get its economy out of deflation?” Peterson Institute of International Economics, November 1, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/will-chinas-stimulus-be-enough-get-its-economy-out-deflation.

[29]. “What you need to know about China’s $1.4 trillion debt package,” Reuters, November 10, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/what-you-need-know-about-chinas-14-trillion-debt-package-2024-11-10/.

[30]. Philip Blenkins, “EU Slaps Tariffs on Chinese EVs, risking Beijing backlash,” Reuters, October 29, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/business/autos-transportation/eu-impose-multi-billion-euro-tariffs-chinese-evs-ft-reports-2024-06-12/.

[31]. “Brazil, India and Mexico are taking on China’s exports. To avoid an economic shock, they are pursuing a strange mix of free trade and protectionism,” The Economist, May 23, 2024. URL: https://www.economist.com/finance-and-economics/2024/05/23/brazil-india-and-mexico-are-taking-on-chinas-exports.