After three years, China remains mired in a deep housing and real estate slump. According to a March 21, 2024 report from the leading global investment firm KKR,[1] this housing recession may not be ending anytime soon. Based on a comparison to the housing bubbles in the US, Japan and Spain, KKR concludes that the Chinese “housing market correction may be just halfway complete.”

If true, this is very bad news, as it comes on the heels of an already sharp contraction in China’s real estate sector. In a June 25th Financial Times editorial,[2] highly respected China economic observer, Chen Long, summarizes the fall in Chinese housing activity. Basing his calculations on official Chinese Government data, Chen notes that on a rolling 12-month basis, home sales in China have dropped to 850 million square meters, or roughly 8.5 million apartments, which is half the level of three years ago. He further notes that the floor space of construction starts have gone down to 620 million square meters, or two-thirds below its early 2021 peak. The share of real estate and construction activities in China’s economy has fallen to its lowest level since 2009. Last but certainly not least, housing prices have fallen by nearly 20% across the country, although this figures masks considerable regional variation across cities (more on those differences later in the blog post). Chen is hardly exaggerating when he writes, “we have witnessed one of the greatest housing market corrections in economic history.”

This real estate meltdown was initially triggered by government efforts in late 2020 to cool down the property market. That is when President Xi, concerned about speculation in the housing market and excessive leverage by developers associated with their debt-driven model of home building, initiated a liquidity squeeze on real estate firms. That squeeze consisted of his now infamous “three red lines.” Under these new rules, liabilities could not exceed 70% of assets (excluding advance proceeds from projects sold on contract), net debt could not exceed 100% of equity, and money reserves had to equal at least 100% of short-term debt. This move quickly set off a chain reaction leading to the bankruptcy of dozens of big and heavily leveraged private developers,[3] including industry giants like Evergrande, Country Garden, and China Vanke.

Unable to access easy credit, these firms ceased construction of unfinished apartment complexes. Since it is the norm for Chinese homebuyers to purchase their apartments before they are finished, those who bought pre-sold units in such partially completed projects and made down payments and took out mortgages on them were left in the lurch. These so-called “烂尾楼 (Làn wĕi lóu),” or “rotten tail” projects, generated understandable anger among these ordinary homebuyers, who felt they had been duped by developers. By 2022, these people took to the streets across China in protest[4]—besides distressed developers, they directed their ire toward banks for failing to safeguard their money.

Those protests, the ongoing importance of the real industry, which accounted for around a quarter of China’s economy in 2021,[5] combined with the double-whammy inflicted by the effort to pop the property bubble and negative impact of Covid and attendant lockdowns, led Chinese governmental authorities to ditch the “three red lines” framework. Starting in late 2023, housing policy in Beijing and local governments shifted dramatically from tightening to easing. As Chen observes in his Financial Times editorial, “housing policies are now at the loosest of all time in most parts of China.”

Thus, after the July 2023 Politburo meeting in which top decision-makers recognized the need to prop up the real estate sector, measures aimed at doing that, in the words of China’s leading financial publication, Caixin,[6] “sprouted like mushrooms after it rains” in cities across the country. These included the first-tier mega metropolises of Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, and Shenzhen, which had previously sought to limit speculative property purchases, a policy that echoed President Xi’s admonition that “houses are for living, not for speculation.” The definition of first-time homebuyers was relaxed to allow more of them to qualify for lower down payments and mortgage rates. As Caixin notes, this marked the first time in three years that lending curbs in China’s four first-tier cities had been loosened. At the same time, the central bank, the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) and National Administration of Finance cut the minimum down payments[7] for mortgages to 20% for first-time buyers and 30% for second-time buyers nationwide. Other steps to revive the housing market[8] included the biggest ever reduction in mortgage rates, as well as trial programs to get residents to trade in old apartments and buy new ones.

As the figures on the ongoing slump in China’s property market noted earlier make clear, none of these measures moved the needle in a positive direction. This failure led national and local governmental authorities to introduce further stimulus measures in May of this year. China’s four first-tier megacities[9] once again slashed downpayment requirements and allowed room for cheaper home loans. The PBoC[10] announced it would facilitate $138 billion in extra funding for property and further ease mortgage rules, while local governments were directed to buy “some apartments.” This last measure has been touted as “historic,” and the New York Times[11] reports that $41.5 billion has been committed to help fund loans for state-owned companies, who have been instructed by local governments to start buying unwanted flats. According to Vice Premier He Lifeng, these units would be used to provide affordable housing for less affluent Chinese.

The plan to have governmental entities to get into the housing business by purchasing unsold housing units raises a number of thorny issues. A Shanghai-based developer quoted anonymously on this move in a May 17th Reuters[12] article on the latest housing rescue package states, “Psychologically, it’d let investors think the government is ‘paying the bill,’ and it is shifting the risks from property developers to banks and local governments.” By letting property developers off the hook for reckless overexpansion, it raises the issue of moral hazard: these actors will be tempted keep taking unwarranted risks in the expectation of being bailed out by a third party down the road. Another more fundamental issue, however, is whether local governments are really capable of buying all of the unsold apartments and their ability to find buyers for them. The New York Times article on this scheme notes that estimates of what the government would need to spend to get the unwanted flats off of the market amounts to between $280-560 billion, well above the sum that has been allocated to do this. Moreover, due to their reliance on revenue from land sales, which has sharply contracted during the housing crisis, Chinese local municipal governments are very short of funds. Some have even sought to reduce medical benefits for seniors,[13] which sparked widespread protests across China. I am skeptical about their ability to fulfill even the modest scale of purchases envisaged in the plan to take unsold apartments off the market, let alone perform the real heavy lifting necessary to do that.

The vast sums of money involved in this herculean task underscores the basic problem underlying all of the short-term Chinese Government fixes for the real estate slump. That problem is China’s massive oversupply of housing stock. While the numbers here vary a lot, they are all pretty eye-watering. According to Bloomberg Economics,[14] as of June, China had 60 million unsold apartments, which will take more than four years to sell off without government intervention. An August 22, 2023 New York Times article[15] cited a similar figure, putting the number of unwanted housing units at 65-80 million. In February, Nikkei[16] put the number of Chinese who could be housed in their country’s excess housing stock at 150 million. Former deputy head of the Chinese National Statistical bureau, He Keng, argues that that figure should be much higher. In a display of candor unusual for a Chinese government official, even one in retirement, He claimed[17] in a September 2023 forum held in the southern city of Dongguan that China’s 1.4 billion people “probably can’t fill” all of its vacant flats. It also bears noting here that according to the New York Times article on the government plan to purchases unsold apartments, China still has 10 million “烂尾楼 (Làn wĕi lóu),” “rotten tail” projects.

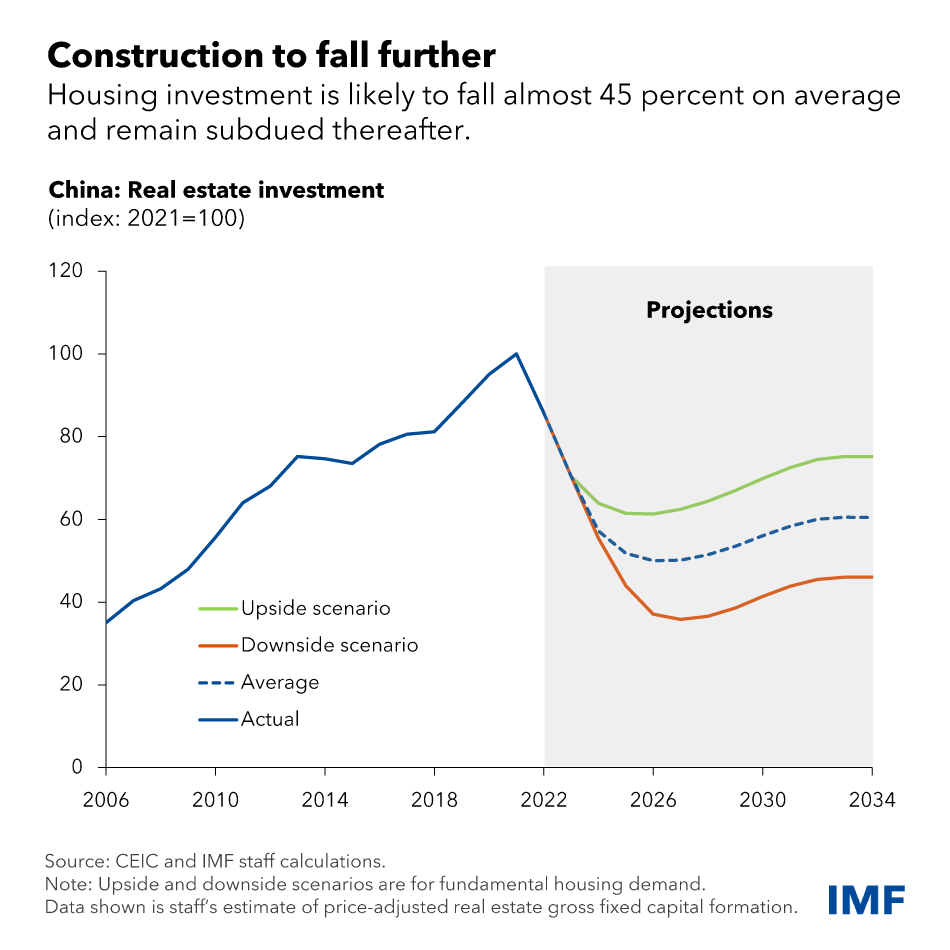

China’s dreadful demography will make cleaning out this huge inventory of excess housing all the more difficult. The rapid aging of China has led to the hollowing out of its young and middle-aged adult population—precisely the people who are the prime homebuyers. According to Nicholas Eberstadt,[18] holder of the Henry Wendt Chair in political economy at the American Enterprise Institute Washington think tank, between 2015-2040, the number of Chinese aged 30-49 will shrink by 25%, or well over 100 million men and women. At the same time, the pace of urbanization in China,[19] which had previously fueled high demand for housing in the cities, is slowing and by 2035, this process will have run its course, putting further downward pressure on housing demand. The IMF therefore projects that real estate investment will likely fall between 30 to 60% from its 2022 level, rebounding only very gradually.

ConstructiontoFallFurther

Source: Henry Hoyle and Sonali Jain-Chandra, “China’s Real Estate Sector: Managing the Medium Term Slowdown,” International Monetary Fund News, February 2, 2024.

As noted at the start of this blog, while housing prices have contracted throughout China, this decline has varied across different cities. That is especially true when it comes to upper- vs. lower-tier metropolises. For those unfamiliar with the different tiers for ranking Chinse cities, tier 1 cities comprise the most developed and desirable metropolises, especially for foreign investment, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou. Tier 2 cities are ones with lower GDPs than their tier 1 counterparts, but are still attractive investment destinations, such as Chengdu and Qingdao. Tier 3 cities consist of poorer provincial capitals and ones of more limited political and economic significance with large populations. Fourth tier cities are ones with low GDPs, but are still developing and urbanizing, while those falling into tier 5 tier comprise China’s poorest urban areas. Metropolises falling into the tier 3 or below category have been most heavily impacted[20] by China’s real estate slump.

The picturesque town and tourist hotspot of Dali in Yunnan Province in Southwest China exemplifies the property woes of lower-tier Chinese cities.[21] Housing prices there had been declining since mid-2021, before making a very modest rebound over the last year, while investment in real estate development plunged by 43% through April 2023. As is the case with other lower-tier cities, a main driver of the Dali’s real estate squeeze is its declining population. During the 2010-2020 decade, the number of people in the Dali prefecture shrank by 120,000. Over this same period, the growing housing surplus was further fueled by long-time overinvestment and overbuilding. Disclosure alert: during my decade-plus years of living in China, I spent about a week in Dali and thoroughly enjoyed my time there (and even wrote an article about it in High Above, the in-flight magazine of Hainan Airlines). One memory of the trip was wandering about a housing development outside the old town of Dali, whose ancient walls are still intact, consisting of brand-spanking new high-end villas. When I asked a couple of locals about that complex, they said that all of the units were vacant and doubted if they would be occupied anytime soon.

Lower-tier cities like Dali have the largest oversupply of housing in China. In a September 2022 International Monetary Fund Occasional Paper,[22] Harvard economist Kenneth Rogoff and Yang Yuanchen estimated that the aggregate total housing stock in tier 1-3 Chinese cities rose from 39 billion to 56 billion square meters between 2010-2021. They note that tier 3 cities accounted for 78% of the growth in the housing stock over that decade, despite being home to 66% of Chinese urban residents. Rogoff and Yang estimate that between now and 2035, real estate construction in such places will have to shrink by roughly 30%.

A key factor encouraging developers to overbuild in lower-tier cities has been misguided Chinese government efforts to encourage “balanced” urbanization. Authorities have sought to redirect the flow of people away from upper-tier metropolises, especially the big megacities, to smaller urban centers. This can be seen in the modest 2014 reform of the so-called 户口 (hùkŏu) household registration system. Under this framework, Chinese born in rural villages receive rural hùkŏus and can only access government health insurance, welfare, and pension schemes for rural residents, which are much less generous than those given to city-dwellers with urban hùkŏus. The 2014 hùkŏu reform[23] made it easiest for villagers to exchange their rural for urban hùkŏus when they moved to the lowest-tier towns and set forth progressively stricter standards for doing this in upper-tier metropolises (next to impossible in places like Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou). However, ordinary Chinese have been voting with their feet, opting to relocate to top-tier cities, which offer greater economic opportunity. Besides the hùkŏu reform, Chinese policymakers sought to boost smaller cities in interior provinces by giving them more land quotas for real estate development—in China, all land is still owned by the state—compared to their upper-tier counterparts. These measures incentivized property developers to build more housing[24] in such places in anticipation of higher demand for it.

I also saw first-hand the housing glut in lower-tier Chinese cities while making frequent visits to the drab fourth-tier metropolis of Panjin in Liaoning Province in northeast China. I was working as a “corporate trainer” for the Great Wall Drilling Company, which is a subsidiary of one of China’s two flagship state-owned oil companies, the China National Petroleum Company (CNPC). The managers of the training center at the Beijing headquarters of the firm sent me and the other foreigner working there, a Canadian fellow, up to Panjin to provide engineers with basic English instruction before they were sent to work on CNPC projects outside of China. While walking about and being driven around Panjin, I was struck by all the shiny new apartment towers that were sprouting up around the city like weeds. One time as I was being driven to the Panjin train station to go back to Beijing and passed by a cluster of high-rise apartment blocks, I asked my driver about all that construction. He told me that those particular structures had not only failed to find buyers and were all vacant, but they were likely going to be torn down, citing extremely shoddy construction work. Yet another example of what the Chinese call 豆腐工程 (dòufu gōngchéng), or “tofu engineering.” This story, I might add, occurred in 2013 or early 2014, years before the Chinese real estate bubble popped.

To sum up, lower-tier Chinese cities are facing now and into the future a triple whammy when it comes to housing. Besides being significantly overbuilt and home to the bulk of China’s excess housing stock, demand will be squeezed by two adverse population trends. The first is the overall fall in the young to middle-aged adult population who are the biggest homebuyers. The second is the pattern of internal migration in China. As noted above, when rural Chinese leave their villages to head to cities, they do not go to lower-tier urban centers, but instead head to upper-tier metropolises offering better economic prospects. The same holds true for city-to-city migration.[25] Housing demand in lower-tier cities will be hammered not just by China’s overall bad demography, but by the out-migration of their residents to higher-tier metropolises. All of this means that the effort to have local government authorities purchase vacant apartments in lower-tier cities, where the oversupply of housing is the greatest, is bound to fail. Given future trends in the demand for housing in such places, local governments will be hard-pressed to find buyers for the vacant housing units acquired under this scheme. In short, there is little prospect in the near or long-term future for a housing market rebound in lower-tier Chinese cities.

The bleak prospects for housing markets in these metropolises does not bode well for the economic future of China. Some 70% of Chinese live in these cities[26] and even as the number of their residents shrinks, due to out-migration to higher-tier urban centers, they will remain home to a huge chunk of the country’s population. As is true for ordinary Chinese in general, homes are the only real store of wealth for lower-tier city dwellers. Government “financial repression”—the suppression of interest rates on bank savings deposits—dodginess of Chinese equity markets and other investment products, and capital controls limiting the ability to invest abroad make buying a home the one path for accumulating wealth for those in the middle-class. Rather than having a store of value, middle-class Chinese residing in lower-tier cities will be stuck with a depreciating asset and will consequently feel poorer. That, in turn, will make them less inclined to buy goods and services, further hindering efforts to rebalance the Chinese economy toward consumption. Lastly, as these homeowners age and need to move out of the flats they own—assuming their children have moved to other cities in search of better jobs and cannot move into these vacated units—they will struggle to find buyers for their properties, necessitating unloading them at fire sale prices. All of this will have interesting implications for China’s political and social stability and legitimacy of the ruling Communist Party.

The outlook for housing demand in upper-tier Chinese cities is, at first glance, much less dire than is the case for their lower-tier counterparts. Rather than stagnating or even declining, the population of upper tier cities will continue to expand as most of the 1 in 3 Chinese still living in the countryside choose to move to these metropolises when leaving their villages. However, as Chen Long observes in his Financial Times editorial, the pace of urbanization in China has significantly slowed, with average annual increase in the city population averaging 10 million in 2020-2021, or half the level of the previous quarter century. While new apartments will be have to be built to provide housing for the still rising number of urban-dwellers, that need will be significantly lower than it was during the previous two and a half decades. That need will be further diminished by the large number of vacant apartments in top-tier cities. Chen notes that the slowdown in rural-to-urban migration translates into a 400 million square meter drop in new housing demand, down from 900 million square meters during the period of rapid urbanization (again most of this new housing demand will be in upper-tier metropolises). He concludes that real estate in top-tier urban markets may begin to rebound late this year or next year, but that rebound will be relatively modest. This view is echoed by Lynn Song, chief economist for Greater China, Hong Kong, who, after the mid-July release of government economic data on 2nd quarter growth in 2024, stated in a Reuters article,[27] “we saw some stabilization (of housing prices) in some key tier 1 and 2 cities.”

But even as more people relocate to upper-tier Chinese cities to prop up the demand for housing in such places, another major issue is whether these new residents can afford to buy flats in such places. While apartment prices in these metropolises have come down some during the recent property slump, they remain relatively high. Measured in price-to-income ratios, a commonly used yardstick measuring housing affordability, Chin’s four tier-1 metropolises of Beijing, Guangzhou, Shanghai, and Shenzhen are now among the cities with the least affordable housing in the world.[28] This affordablity crunch exists despite large number of vacant flats in cities like Beijing. The August 22, 2023 New York Times article cited earlier in this blog post notes that affluent upper-tier city resident bought apartments as investments to rent out and thereby accumulate wealth. As more apartments were built toward the tail-end of the real estate bubble, their value as rental properties declined, leaving those who bought them with units whose rent did not pay for their mortgages. Annual rents amounted to 1.5% or less of a flat’s purchase price vs. the 5-6% share claimed by mortgage interest costs. Since Chinese flats are typically delivered by builders as hollow concrete shells without amenities like sinks, or even basics such as flooring, with rents so low, many investor buyers have refrained from finishing apartments in the hope of flipping them for higher prices at a later date. According to the Times, this behavior has been a major factor driving up the vacant housing stock in upper-tier cities.

Fundamentally reforming or doing away altogether with the hùkŏu system could help enable those relocating to upper-tier cities buy housing in their new hometowns. In her important recent book, Social Protection Under Authoritarianism: Health Politics and Policy in China, Rutgers University Professor Huang Xian extensively details how under China’s highly localized and fragmented social welfare system, a wide gap exists not just between rural and urban areas, but across cities as well. Among the latter, China’s social safety net is most threadbare in lower-tier metropolises, especially those outside the wealthier coastal provinces. As noted earlier, the 2014 hùkŏu reform enabled rural villagers to exchange their rural for urban hùkŏu only if they moved to the lowest tier cities. These strictures also applied to individuals wanting to replace hùkŏus from their old lower-tier hometowns with ones from upper-tier cities after relocating to the latter. Scrapping these rules would give migrants from rural villages and other cities access to the more generous social welfare benefits offered in top-tier Chinese cities, as well as free primary through middle-school education for their children and greater employment opportunities. These individuals could then have more money available to purchase apartments in the upper-tier metropolises they now call home.

Unfortunately, little has been done by Chinese governmental authorities to fundamentally alter the hùkŏu system. The latest changes outlined in 2022[29] merely nibbled at the edges of existing hùkŏu rules. Upper-tier cities remain reluctant[30] to allow migrants from rural areas and other cities to exchange their old hùkŏus for ones in their new places of residence. Despite their relative affluence, these cities fear they will be unable to afford doing that, and those fears have been accentuated by the squeeze on local finances caused by declining revenue from land sales[31] stemming from China’s real estate slump. I also strongly suspect that further opening the door to migrants might not sit well with long-time residents in cities like Beijing and Shanghai. During my 11 years of living in Beijing, one thing I head time and time again from the locals was “北京人态度了 (Bějīng Rén tài duōle),” or “too many people in Beijing!” These individuals, I might add, were typically lucky duckies who by dint or being born in the capital or good fortune, possessed the coveted Beijing hùkŏus.

Even in the highly unlikely event that the Chinese government quickly enacts policies boosting the incomes migrants to top-tier cities, the long-term outlook for real estate in these metropolises is far from rosy. Their day of reckoning will come in the mid-2030s. By that time, rural to city migration with have run its course; as is currently the case among advanced economies in Asia, North America, and Europe, 80-90% of China’s population will live in urban areas. While top-tier cities will continue to receive in-migration from lower-tier cities, it is unlikely that this will come close to offsetting the loss of rural migrants.

This loss of rural migrants matters a lot because while China’s overall demography is bad, it is absolutely terrible in its top-tier cities. The fertility rate, or number of children a woman will give birth to in her lifetime, among Chinese women has now fallen to 1.15 births,[32] well under the replacement rate of 2.1 needed for a country to sustain its population. Fertility rates among women in top-tier cities are even lower, with the rate among women in Shanghai coming in at 0.70 in 2022.[33] In a February 21st Guardian article[34] on the high costs of raising children in China, prominent writer Zhang Lijia, who has explored changing attitudes toward marriage and motherhood among Chinese women, observes, “Many women I interviewed simply couldn’t afford to have two to three children. Some can manage one; others don’t even want to bother with one.” In a comment clearly referring to professional ladies living in top-tier cities, she adds, “Many urban educated women no longer see motherhood as the necessary passage in life or the necessary ingredient for happiness.” In the absence then of the buffer provided by in-migration, the population of top-tier Chinese cities can be expected to contract sharply following 2035, leading to a steep fall in the demand for housing. Once that happens, the housing markets in these metropolises will increasingly resemble the situation now prevailing in tier 3-5 urban centers.

Before this occurs, for the next decade at least, the Chinese real estate and housing market will be a tale of two sets of cities, top-tier metropolises and their lower-tier counterparts. In the long run, however, there is little chance in either of these cases of this story ending happily.

[1]. Evelyn Cheng, “KKR says China’s real estate correction may be only halfway done,” CNBC, April 3, 2024. URL: https://www.cnbc.com/2024/04/03/kkr-says-chinas-real-estate-correction-may-only-be-halfway-done.html.

[2]. Chen Long, “China’s Big Housing Correction is not over. Better-case scenario is that sales start to stabilize near the end of 2025,” Financial Times, June 25, 2024. URL: https://www.ft.com/content/38f32adf-fc91-4f3c-a5df-69c676da646e.

[3]. James Dorn, “Anatomy of China’s Housing Crisis: Ending Financial Repression,” Cato Institute Blog, November 14, 2023. URL: https://www.cato.org/blog/anatomy-chinas-housing-crisis-ending-financial-repression.

[4]. Shuli Ren, “China Housing’s ‘Rotten Tails’ need a Lehman Solution. Distressed developers are unable to deliver tens of millions of homes they pre-sold, as banks are reluctant to tap emergency lending facilities,” Bloomberg, November 21, 2023. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2023-11-21/china-s-developers-can-t-get-bank-loans-to-finish-homes?embedded-checkout=true.

[5]. Kenneth Rogoff, “Diminishing Returns on Real Estate Threaten Chinese Economic Growth,” East Asia Forum, December 7, 2023. URL: https://eastasiaforum.org/2023/12/07/diminishing-returns-on-real-estate-threaten-chinese-economic-growth/.

[6]. Wang Jie, “Opinion: Can China’s Latest Policies Turn the Tide on the Housing Slump?” Caixin Global, September 5, 2023. URL: https://www.caixinglobal.com/2023-09-05/opinion-can-chinas-latest-policies-turn-the-tide-on-housing-slump-102100661.html.

[7]. Laura He, “China takes aim at the real estate crisis with new measures to boost the economy,” CNN, September 1, 2023. URL: https://www.cnn.com/2023/09/01/economy/china-mortgage-stimulus-intl-hnk/index.html

[8]. Alexandra Stevenson, “China has a plan for its Housing Crisis. Here’s why it’s not Enough,” New York Times, May 24, 2024. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JihHCuH7FC8

[9]. “Chinese Mega Cities Loosen Homebuying Rules as Aid Spreads,” Bloomberg, May 28, 2024. URL: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-05-29/chinese-mega-cities-loosen-homebuying-rules-as-aid-spreads

[10]. Liangping Gao, “China unveils ‘historic’ steps to stabilize crisis-hit property sector,” Reuters, May 17, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/china-new-home-prices-fall-fastest-pace-over-9-years-2024-05-17/.

[11]. Alexandra Stevenson, “China has a plan for its Housing Crisis. Here’s why it’s not Enough,” New York Times, May 24, 2024. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JihHCuH7FC8.

[12]. Liangping Gao, “China unveils ‘historic’ steps to stabilize crisis-hit property sector,” Reuters, May 17, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/markets/asia/china-new-home-prices-fall-fastest-pace-over-9-years-2024-05-17/.

[13]. Laura He, “Chinese cities are so broke, they’re cutting medical benefits for seniors,” CNN (Hong Kong), March 31, 2023. URL: https://www.cnn.com/2023/03/31/economy/china-pension-protests-aging-society-intl-hnk/index.html.

[14]. “China’s push to clear huge inventory of unsold homes to bring developers little cheers,” The Straits Times, June 10, 2024, URL: https://www.straitstimes.com/business/china-s-push-to-clear-huge-inventory-of-unsold-homes-to-bring-developers-little-cheer#:~:text=HONG%20KONG%20%E2%80%93%20China’s%20efforts%20to,prices%2C%20analysts%20and%20developers%20say.

[15]. Keith Bradsher, “Why it’s so hard for China to fix its Real Estate Crisis,” New York Times, August 22, 2023. URL: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/22/business/china-economy-property.html.

[16]. Ushuo Cho, “Housing glut leaves China with excess homes for 150 million people,” Nikkei, February 3, 2024. URL: https://asia.nikkei.com/Spotlight/Datawatch/Housing-glut-leaves-China-with-excess-homes-for-150m-people,

[17]. “Even China’s 1.4 billion population can’t fill all its vacant homes, former official says,” Reuters, September 24, 2023. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/even-chinas-14-bln-population-cant-fill-all-its-vacant-homes-former-official-2023-09-23/.

[18]. Nicholas Eberstadt, “China’s Demographic Outlook to 2040 and its Implications: An Overview,” American Enterprise Institute, January 2019. URL: https://globalcoalitiononaging.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/China%E2%80%99s-Demographic-Outlook.pdf.

[19]. Alicia Garcia Herrero, “China’s Aging Problem will be much more serious when urbanization is completed,” China Leadership Monitor (CLM), Issue 80, June 2024. URL: https://www.prcleader.org/post/china-s-aging-problem-will-be-much-more-serious-when-urbanization-is-completed.

[20]. Tanner Brown, “China’s Property Bubble Popped. These Cities are Taking the Brunt,” Barron’s, March 10, 2024. URL: https://www.barrons.com/articles/china-property-bubble-popped-these-cities-taking-the-brunt-906d51b2.

[21]. Tianlei Huang, “Housing Surpluses in some places and shortages in others reflect China’s failed economic strategies,” Peterson Institute of International Economics, June 14, 2023. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/housing-surpluses-some-places-and-shortages-others-reflect-chinas-failed.

[22]. Kenneth Rogoff and Yang Yuanchen, “A Tale of Tier 3 Cities,” IMF Working Paper WP/22/196, September 2022. URL: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2022/09/29/A-Tale-of-Tier-3-Cities-524064.

[23]. Richard Silk, “Republican Hukou Reform Plan Starts to Take Shape,” Wall Street Journal, August 4, 2014. URL: https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-CJB-23419.

[24]. Tianlei Huang, “Why China’s Housing Policies have Failed,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, URL: https://www.piie.com/publications/working-papers/2023/why-chinas-housing-policies-have-failed.

[25]. Tianlei Huang, “Housing Surpluses in some places and shortages in others reflect China’s failed economic strategies,” Peterson Institute of International Economics, June 14, 2023. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/housing-surpluses-some-places-and-shortages-others-reflect-chinas-failed.

[26]. Grace Yan, “Consumption Potential in China’s lower-tier cites,” Nikko Asset Management, January 20, 2023. URL: https://en.nikkoam.com/articles/2023/consumption-potential-in-chinas-2301#:~:text=The%20lower%2Dtier%20cities%2C%20numbering,million%20inhabiting%20third%2Dtier%20cities.&text=This%20means%20a%20majority%20of,such%20often%20overlooked%20urban%20areas.

[27]. “Analyst views on China’s second quarter GDP growth,” Reuters, July 14, 2024. URL: https://www.reuters.com/world/china/view-chinas-q2-economy-grows-slower-than-forecast-2024-07-15/#:~:text=%22The%204.7%25%20growth%20is%20quite,’around%205%25’%20target.

[28]. “Property Prices Inex by City 2024 Mid-Year,” Numbero, No date. URL: https://www.numbeo.com/property-investment/rankings.jsp.

[29]. Edward Jaramillo, “China’s Hukou Reform in 2022: Do They Mean it this Time?” Center for Strategic and International Studies, Blog Post, April 20, 2022. URL: https://www.csis.org/blogs/new-perspectives-asia/chinas-hukou-reform-2022-do-they-mean-it-time-0.

[30]. Reforms to China’s hukous system will not help migrants much. Big cities are still reluctant to give them social benefits,” The Economist, September 22, 2022. URL: https://www.economist.com/china/2022/09/22/reforms-to-chinas-hukou-system-will-not-help-migrants-much.

[31]. Huang Tianlei, “China’s property downturn continues to drag down government spending,” Peterson Institute for International Economics, February 5, 2024. URL: https://www.piie.com/blogs/realtime-economics/2024/chinas-property-downturn-continues-drag-down-government-spending.

[32]. Carl Minzer, “China’s Population Decline Continues,” Council on Foreign Relations, January 26, 2024. URL: https://www.cfr.org/blog/chinas-population-decline-continues#:~:text=Statistics%20suggest%20that%20China’s%20total,would%20maintain%20current%20population%20levels.

[33]. Zhou Wenting, “Shanghai weighs options to tackle birthrate decline,” China Daily, April 1, 2024. URL: https://www.chinadaily.com.cn/a/202401/27/WS65b44481a3105f21a507e9ee.html#:~:text=The%20latest%20Shanghai%20Health%20Commission,one%20of%20the%20lowest%20nationally.

[34]. Amy Hawkins, “Cost of raising children China second-highest in the world, think tank reveals,” The Guardian, February 21, 2024. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2024/feb/21/cost-of-raising-children-in-china-is-second-highest-in-the-world-think-tank-reveals.